The artist’s lifework is an ongoing confrontation with those who would deny his homeland’s existence

If there’s one thing that Khaled Jarrar knows how to make, it’s the news. In 2014 the artist made international headlines when Israeli security forces barred him from crossing into Jordan from the West Bank to catch his flight to New York for the opening of Here and Elsewhere, the New Museum’s survey of contemporary art from the Arab world. The story highlighted the bureaucratic and infrastructural matrix that Palestinians navigate in occupied Palestine, as documented in Jarrar’s 2012 film, Infiltrators, included in the New Museum exhibition. Footage shows Palestinians finding ways to cross the Israeli separation wall that cuts across the West Bank, for reasons as quotidian as attending school. Jarrar himself is no stranger to these daily feats. When planning to attend an interview at the American consulate in Jerusalem for his us visa application in 2014, he learned that Israeli authorities had cancelled most permits due to the ongoing war on Gaza, so he smuggled himself in.

Things blew up again in 2015 – the year Jarrar accompanied a Palestinian family on their gruelling journey from Syria to Germany, recorded in his remarkable 2022 documentary, Notes on Displacement – when the artist painted a giant rainbow flag on the West Bank separation wall near the Qalandiya checkpoint (Through the Spectrum, 2015). Responding to rainbow profile overlays appearing on Facebook after same-sex marriage was legalised in the US (the pride flag was also projected onto the White House that year), he felt compelled to highlight another oppressed group’s plight. ‘The apartheid wall, built in violation of international law, cuts across our land and our water,’ Jarrar wrote in a July 2015 article for The Electronic Intifada. ‘I wanted the world to see that our struggle still exists and I felt there could be no better place to have that dialogue than on the concrete slabs of the most visible icon of our oppression.’ Jarrar’s opinion piece reacted to coverage by The Associated Press that focused on the backlash his painting received in Palestine, fortifying a deadly, pinkwashed narrative that pitted ‘liberal’, ‘queer-friendly’ Israel against the weaponised stereotype of a ‘conservative’, ‘homophobic’ Palestine (the latter narrative propagated by The Guardian and Haaretz).

In the aftermath, Jarrar continued to pop up in the news cycle. In 2016 The Guardian and the Los Angeles Times featured his project with mobile art-producers Culturunners: he pulled off an old piece of a new section of the US–Mexico border wall and turned it into a ladder-shaped sculpture that was installed in the Mexican city of Juárez. In 2018 Artnet and Hyperallergic wrote about Blood for Sale, a public performance presented in conjunction with Jarrar’s exhibition at Open Source Gallery in New York, for which he stood on Wall Street for one business week selling ten-millilitre vials of his blood to draw attention to America’s military-industrial complex. Prices started at $19.48, the year of the Nakba, before following the stock price of America’s 15 largest defence contractors, including BAE Systems and Lockheed Martin; in the end, the artist says, proceeds went to a hospital in Gaza.

Jarrar began researching Blood for Sale while developing I Am Good at Shooting, Bad at Painting, a performance staged in the Arizona desert in May 2018 with MoCA Tucson. Making use of his military training, the artist created abstract paintings by firing an AR-15 assault rifle at vials of paint positioned between two canvases angled towards each other. The work, which referenced the CIA’s weaponisation of Abstract Expressionism during the Cold War, extended a 2015 performance staged by the artist in Geneva with Art Bärtschi & Cie, prompting media coverage and an investigation by Swiss authorities. Video documentation of that 2015 iteration shows Jarrar introducing the performance in Arabic before grabbing his Glock, as if to challenge his European audience to resist the urge to see an Arab holding a gun as a terrorist. (His first paintings-by-gunshot were created in 2014 for a show curated by Inês Valle at Galerie Polaris in Paris and Gallery One in Ramallah.)

After something of a media lull, Jarrar rode the NFT wave in 2021. He minted a token based on a jar of dirt picked up in a village near Ramallah from which the illegal Halamish settlement could be seen: a response to the forced and illegal evictions of Palestinians from their homes in the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah by settlers supported by the Israeli army. ‘Gazing at the landscape that is shrinking daily by annexation, I chose to mark the hypocrisy of Israeli occupation and its unending spectrum of social, economic, and ecological apartheid by NFTing the soil,’ Jarrar told The Art Newspaper at the time. The work’s title, ‘If I don’t steal your home someone else will steal it’ (2021), quotes Jacob Fauci, an Israeli settler from New York, who uttered those words to justify his occupation of the al-Kurd family home in Sheikh Jarrah.

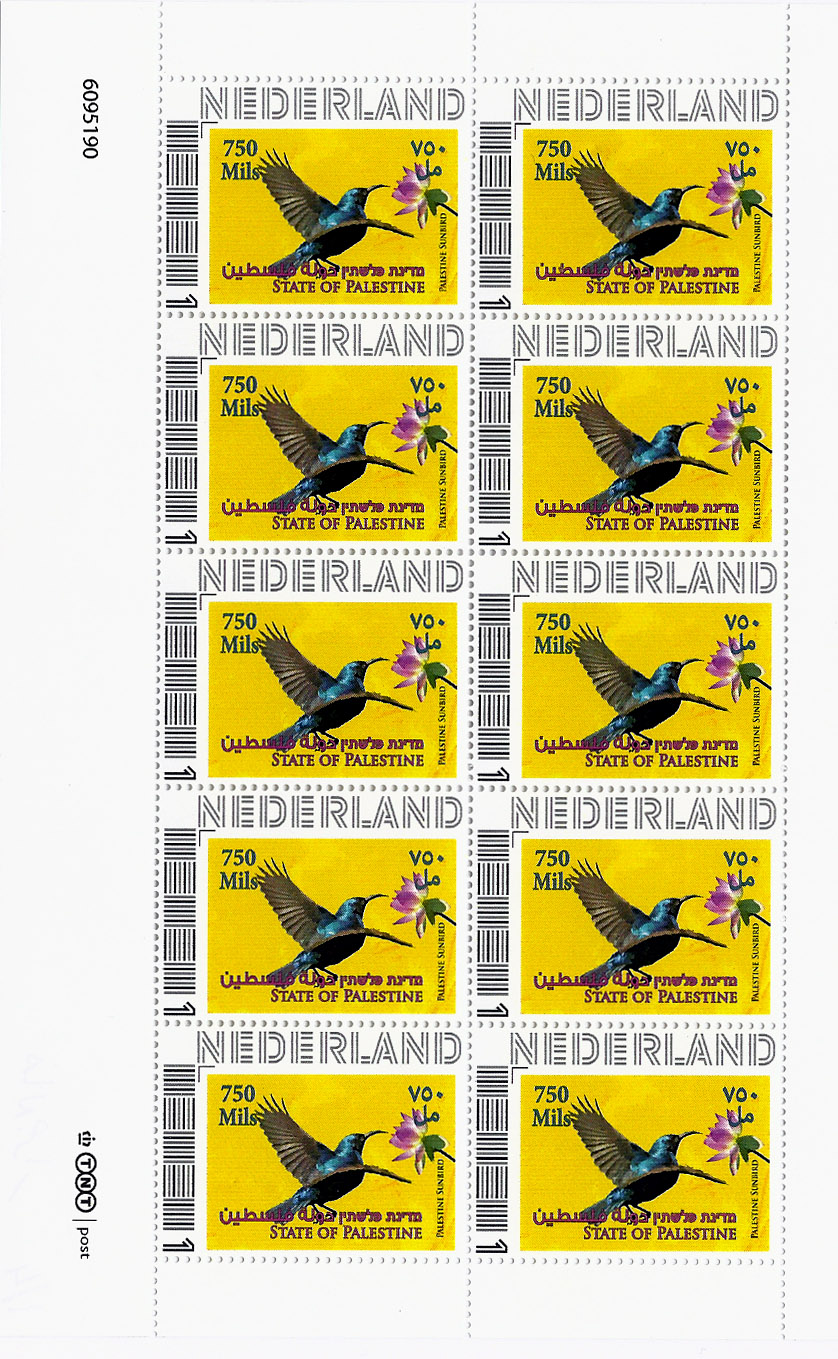

Jarrar first captured the media’s attention in 2011, the year he graduated from the International Academy of Art Palestine. He created a ‘State of Palestine’ stamp, with a design featuring the blue-flecked Palestine sunbird, and began offering – rather daringly, given the trouble the stamp might raise with Israeli authorities – to ink the passports of visitors to the West Bank. Part of the Live and Work in Palestine project (2009–), the initiative was documented by CNN in 2011 ahead of a vote granting nonmember observer-state status to Palestine at the United Nations, with Jarrar stating: “Nobody can deny our existence as Palestinians.”

In 2020 Al Jazeera released a documentary on Jarrar’s State of Palestine project, which has also incorporated the production of postage stamps, starting with a set created using the Deutsche Post AG ‘individual stamp’ service for the 2012 Berlin Biennale, followed by those created with postal services in Belgium, Norway, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands. When his proposal to collaborate with the French postal office was rejected that same year, Jarrar decided to create his own stamps and sold them for 75 cents with Galerie Polaris at the FIAC art fair in Paris.

The State of Palestine icon has since become an enduring symbol. It continues to circulate in different forms, most recently appearing in the iconic music video director Farid Malki made for Palestinian-Jordanian singer Zeyne’s powerful track 7arrir 3aqlak/Asli Ana. It’s also been printed on t-shirts, with or without Jarrar’s permission (he doesn’t mind), and reproduced on hand-painted fridge magnets, with Jarrar’s consent, to sell to tourists. Jarrar sold those magnets himself as part of a 2024 group exhibition at Timespan in Scotland, to raise funds for the nonprofit Disarming Design for Palestine. For that show, he also produced Palestine Sunbird (2024), a lifesize bronze sculpture of a sunbird, perched on a granite block commonly used for gravestones.

Palestine Sunbird is both monument and memorial. Much has changed for Palestine and the artist, after all. In September last year, Palestine was granted a seat at the UN General Assembly, marking a historic moment amid Israel’s devastating assault on Gaza, despite an earlier veto by the us to grant it full UN member status. That ongoing denial of Palestinian existence is mirrored in Jarrar’s latest project. After receiving his temporary green card following his relocation to America in 2023, he discovered that, in another act of erasure, his place of birth was changed from Palestine to ‘unknown’. Jarrar has given that title to the olive oil he plans to auction in clay vessels created in collaboration with master potter João Lourenço, based on an ancient artefact attributed to the Philistines.

Recently presented in his show Land After Art at Forum Arte Braga, organised by the Cera Project and curated by Inês Valle, Jarrar’s ‘unknown’ oil comes from olives he was finally able to harvest in 2022 from his land in the West Bank. He purchased the plot in 2016 with money he made selling sculptures of everyday objects – including a football, Jerusalem bread and an olive tree trunk – cast from concrete chiselled off the Israeli separation wall. Utilising the infrastructure of his oppression and an industry that tends to fetishise it, Jarrar sold these forms easily within the art market, enabling the artist to reclaim a piece of Palestine as his own.

Still, Jarrar’s Palestinian plot naturally tells a collective story. It honours his grandmother Shafiqa, who fled amid the Nakba, losing her family’s land in the Jezreel Valley. As a boy, he helped her harvest olives for other farmers, never understanding why they couldn’t farm their own field – a forced separation that continues to shape the Palestinian condition. Take Jarrar’s uncle, a farmer with no access to his mother’s field, who worked in construction in Israel before he was employed to build the separation wall. ‘It’s important to understand how Palestinians are implicated, more and less directly, in Israel’s settler colonial enterprise,’ Jarrar wrote in The MacGuffin. ‘Like the Palestinians whose only way to make a living is to construct Israeli settlements on Palestinian land, my uncle actively contributed to the physical infrastructures that have imprisoned him.’

Jarrar himself is likewise implicated. Until January 2023 he was employed by the Palestinian Authority, the governing body in the West Bank, as a member of its security forces, which polices the Palestinian population. This background highlights the artist’s undeniably unique life story. Born in Jenin in 1976, he grew up to study interior design at the Palestine Polytechnic University, smuggling himself into Nazareth to work illegally as a carpenter after graduating in 1996. In December 1997 he joined the police force in search of secure employment before swiftly being recruited into the Presidential Guard, completing his training in June 1998 to serve as Yasser Arafat’s bodyguard until the leader’s death in 2004.

The artist continues to reflect on how these violent experiences have shaped him. During the First Intifada, at the age of eleven, he joined hopeful youths from across the Occupied Territories to hurl stones at heavily armed Israeli soldiers in a bid for freedom. In 2002, amid the Second Intifada, he was shot during the siege of Arafat’s compound in Ramallah. “Later I replaced stones for a gun,” he tells me; “then I found art.” But while art has been a vehicle for the artist’s clear-eyed resistance to Israel’s occupation, another thread in his practice embodies a more introspective confrontation with his past as a soldier, first for the Presidential Guard, and then for the Palestinian Authority – a bridge between revolutionary Palestine in the twentieth century and its subsequent pacification post-Oslo, into the twenty-first century.

First performed at Al Mahatta Gallery in Ramallah in 2009, the year Jarrar left active duty to start a media department for the PA’s security forces, The Soldier involved Jarrar standing like a statue in his military uniform on a pedestal. Docile Soldier (2012), included in the 4th Thessaloniki Biennale, comprises photographic portraits of Jarrar’s subordinates, while the video I. Soldier (2011) captures a brigade from above, the camera following their shadows. A later video, I Am a Woman (2018), depicts Jarrar screaming the work’s title in Arabic, a reference to verbal punishments meted out to Presidential Guard recruits who want to quit. Jarrar’s performance confronts the patriarchy that shaped him as a soldier and the power that conditioned him as a result. As he points out, under occupation, “few Palestinians have the luxury of living in a bubble of ideological purity”.

The red beret Jarrar wears in his soldier works is indicative of that impurity. The switch to green berets that occurred around the time of Prime Minister Salam Fayyad’s reforms, Jarrar says, represents the security forces’ transformation, when a new generation of soldiers were trained with Western input, and career politicians and officers proliferated. Reflecting on the neoliberalisation of Palestinian statecraft, Jarrar recalls a photographer telling him about a meeting he documented, when Tony Blair apparently advised Palestinian businessmen to give Palestinians something to lose. “Because when Palestinians have nothing to lose they are fearless fighters,” Jarrar explains. “But give them loans and they can’t resist.”

All the Wounds to Close, his 2023 show with Wilde Gallery in Geneva, confronts this condition with chainmail garments – a mask, beret, brassiere, gloves and socks – made from Israel’s ten-agorot coins, which Arafat highlighted in a 1990 UN address, given the map of ‘Greater Israel’ he saw in its design. (Benjamin Netanyahu wielded a similar map at the UN in September 2023.) The mask in particular points to money’s control over mind and body, a cage in service of colonialism, which circles back to Jarrar’s PA connection. Having pursued an international career as an artist while being employed by the PA, it has been hard for Jarrar to shake off suspicions among some of his peers, whether in the arts or in the security forces, leaving him caught between nation and state.

Perhaps Jarrar’s last ‘State of Palestine’ stamping action was an attempt to transcend that capture. After two days of inking passports in Oslo for Runa Carlsen’s solo show at Fotogalleriet in 2012, he went to the square where the Oslo City Hall is located, a stone’s throw from the Nobel Peace Center where Yasser Arafat, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres received the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize following the 1993 Oslo Accords. These interim agreements, which paved the way for the so-called two-state solution and the Palestinian Authority, led to a betrayal, Jarrar felt, allowing Israel to outsource the occupation to Palestinians like himself. So he placed his original stamp on the ground and smashed it with a hammer. When I ask why he did this, he replies with a warning, if not a personal reminder: “There’s nothing worse than when the oppressed becomes the oppressor.”

Stephanie Bailey is a writer from Hong Kong

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.