The Lakȟóta artist creates space for Indigenous knowledge within the realms of artificial intelligence

In an artist talk, Kite once posed the question, “What are computers, but stones or rare minerals mined from the earth, melted, soldered and transformed into computing machines? Animate stones which emerge from a specific place – an already established web between humans and nonhumans?” These questions centre Lakȟóta cosmological understandings and Indigenous research ethics, guiding her practice as an artist, composer, professor and now head of the Indigenous AI lab at Bard College, Upstate New York. For Kite, computers and stones are intimately linked, Lakȟóta visions and dreaming are research methodologies, and dreams, like artificial intelligences, are not the product of unknowable forces but a complex set of electrical pulses, currents, inputs and outputs.

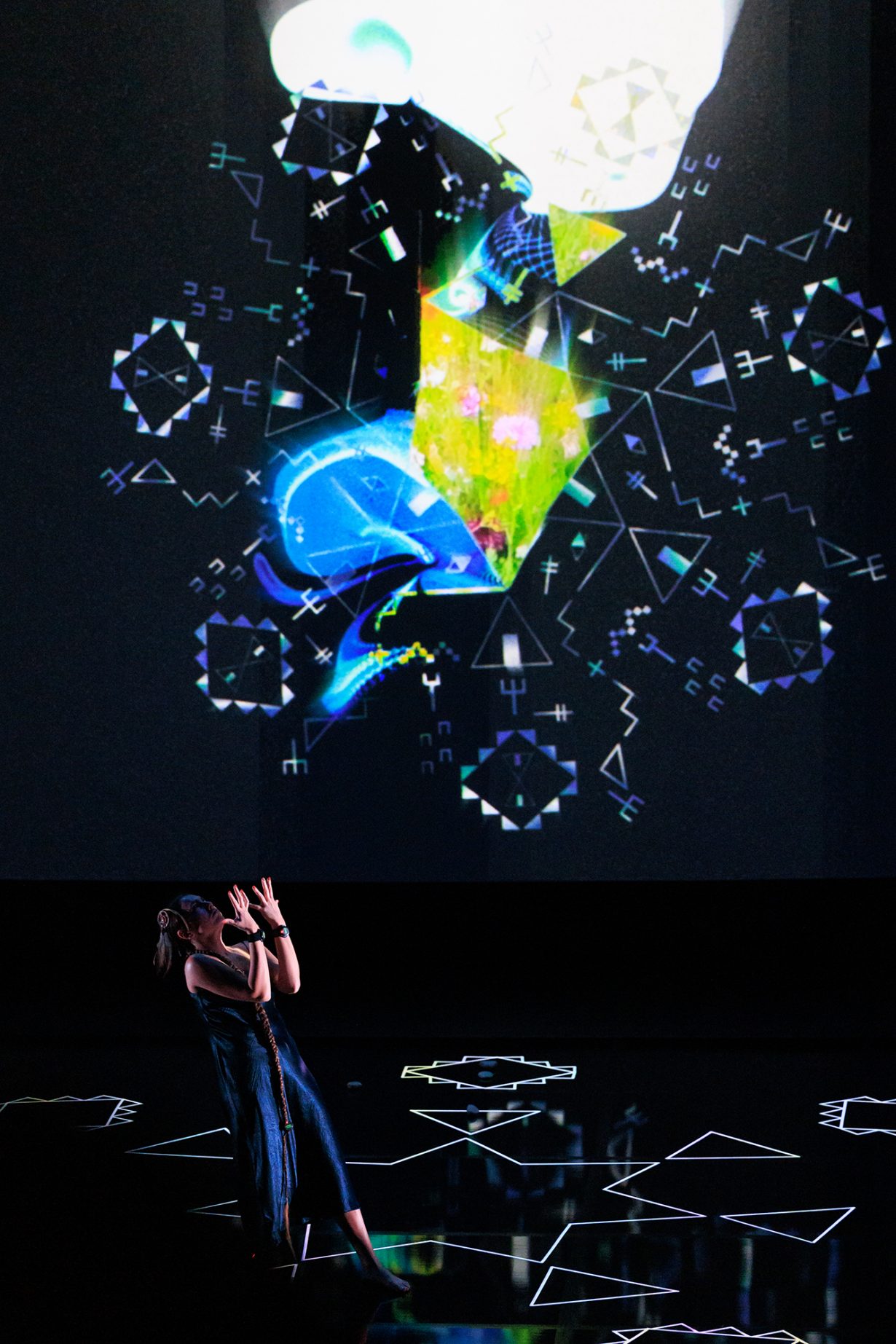

In a recording of one of her soundworks, the lilt of a solo viola stretches out as if it were travelling across an open plain. The sustained tone of the instrument’s voice, punctuated by a slight wavering trill, returns me to the familiar sound of a singer at a ceremony or powwow – though absent is the usual accompanying heartbeat of the drum. Emerging from the ground of this sonic field, shimmering strings fade in and out, dancing like grasses in the wind. Meanwhile, the crackling static of synthesised thunder lingers like a thick cloud. To create this composition, Hél čhankú kin ȟpáye (There lies the road) (2021), Kite moved and manipulated a sensor-embedded, ropelike braid of synthetic that hung from the ceiling. Through AI, the sounds of existing musical improvisations were transformed in real time to create a lush, astral soundscape for her movements and storytelling.

The dreamy, almost magical sound is in fact produced with a machine-learning interface called the Wekinator. As Kite moves through the performance space, slowly draping and bending the suspended braid against and alongside her body, the software collects data from the sensors in the plait, learning her movements and adjusting the sound outputs accordingly in a dance between human and machine. The computer, like another kind of instrument, gives sound to the artist’s physical movements. Unlike a viola or a harp, this hair-braid technology, which appears across Kite’s performance oeuvre as both a research output and a tool of artistic creation, is not just voicing or sonifying, but actively listening and learning too.

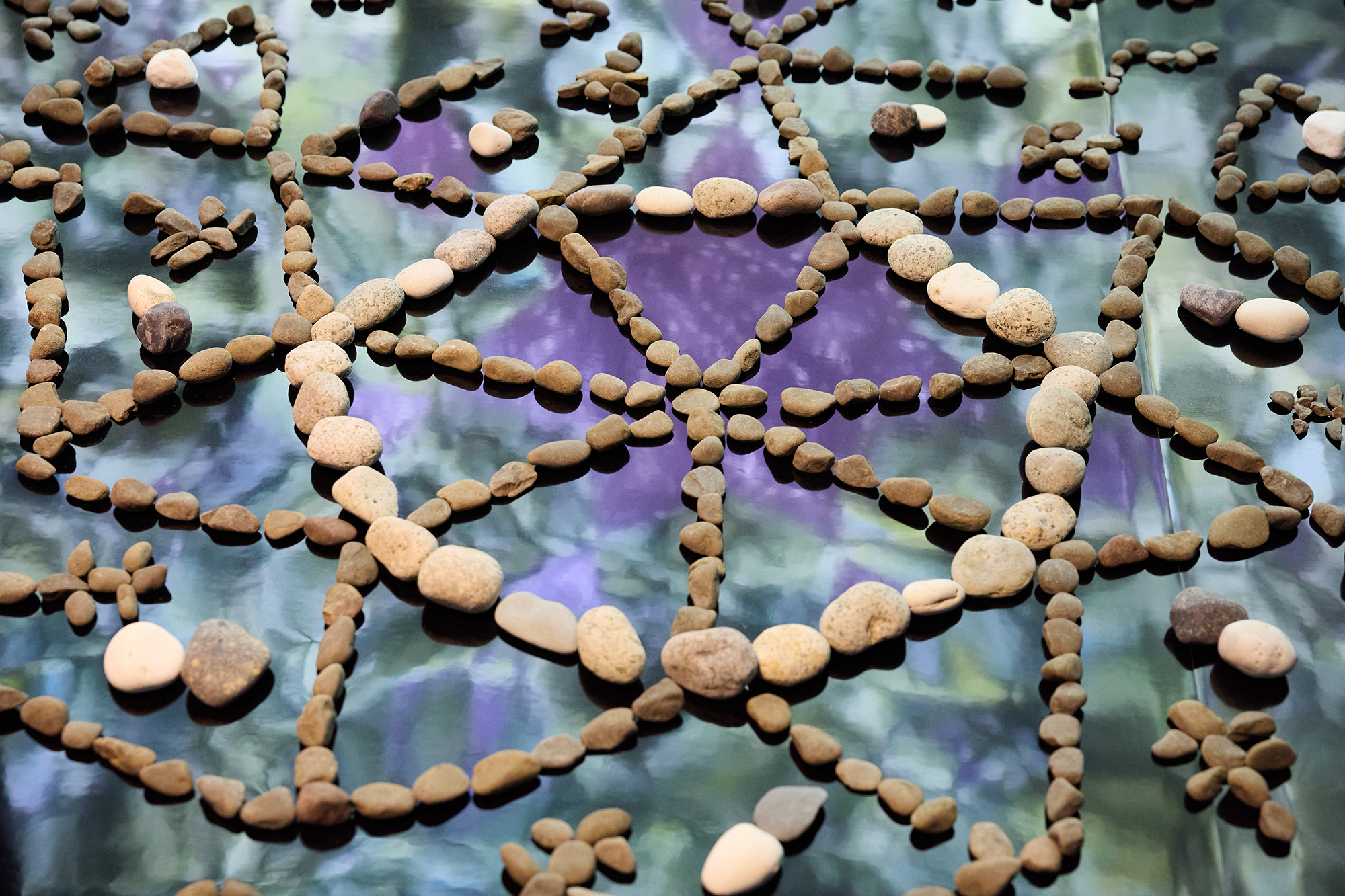

Her recent solo exhibition at MIT’s List Center, List Projects 31: Kite, centres the installation and performance work Wičháȟpi Wóihanbleya (Dreamlike Star) (2024). When I walked with Kite through the dark space of her installation, it felt natural for us to speak quietly. In the modest space of the faintly lit gallery, an animated video of a pool of water (at the bottom of which lies a bed of stones) is projected onto the wall, and the viewer assumes the perspective of someone who has plunged their head beneath the surface. A labyrinthine design of animated geometric patterns and Lakȟóta symbols – forming a Lakȟóta visual text – scatters across the pool of water. Light from the projected video reflects across the polished floor, where we walk around stones similarly arranged in patterns that are AI translations of Kite’s dreams. These stones are both part of the physical installation work and form an instructional score for musicians to follow, should they be able to read it. Drawing on knowledge from Lakȟóta elders like her grandfather Maȟpíya Nážin, these arrangements express Lakȟóta ontologies in which stones are animate beings; they are teachers, storytellers and relatives. While watching the video of Kite’s performance Pȟehínkin líla akhíšoke (Her hair was heavy.) (2019), I chuckled in agreement when I heard her grandfather say, in a voiceover, “We [Indigenous people] have always known about quantum physics. We just didn’t call it that.”

Kite considers some wearable technologies, such as her sensor-embedded hair braid, as extensions of embodied knowledge production. Moreover, they are continuations of traditional technologies made by Indigenous women and passed down by elders. To use another example, a ziibaaska’iganagooday (jingle or prayer dress) is a type of dress adorned with conic metal jingles that originated in Ojibwe communities, conceived of as a kind of sonic healing technology in 1918 during the influenza pandemic. A different technology of adornment, embroidery, features in other works by Kite, such as Thehpi Chapcheyazala Wakhan (Unknowable Black Currant Hide) #1 (2019). Developed as an expansion of Lakȟóta women’s geometric designs, some of these works use conductive thread embroidered onto hides of leather or satin wall hangings. Other embroidered designs are musical scores; others still are the result of AI translations of Kite’s dreams.

It’s easy to think about the act of translation in terms of what is lost to the process – meaning, inflection, intent – but as dreams, knowledge and stories are transformed by Kite from the immaterial to pictorial language to sound, they accumulate new associations and perspectives with each iteration. In making work she considers “legible to [her] elders”, Kite’s practice aligns with that of xwélmexw scholar and artist Dylan Robinson, taking a position against what they call ‘Hungry Listening’ – a term coined by Robinson to describe the settler-colonial refusal to recognise Indigenous song as knowledge, document and law, and the simultaneous desire to consume it. In many of her works that incorporate scores, such as Iktómiwin (My Grandfather’s Vision) (2023), an installation that exists as both a physical arrangement of stones and a written score for musicians, the geometries unveil multiple registers of legibility across different communities – Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Through this range of legibility, she affirms the idea that “our [Indigenous] knowledge is not for all people, nor for at all times”.

When Kite activates Wičháȟpi Wóihanbleya through her performance, she uses her body and her braids to create a ‘Lakȟóta dataset’, which is taught to the software on the computer – or as the artist puts it, a machine made of stones and rare minerals. Though she has performed this work at institutional exhibition spaces, including MIT’s List Center and HKW in Berlin (2024), Kite’s work refuses to be positioned as a conceptual fetish object of the Western system of documentation or museum vitrine. Her commitments to Indigenous research protocols are best outlined in her research paper ‘How to Build Anything Ethically’ (2019), in which she maintains the specificity of her Lakȟóta understandings and cosmologies, and prioritises her work’s legibility to Indigenous people. Her collaborators are diverse: musicians, researchers, her relatives. And as a kind of conduit (or conductor), her work allows her to move research funds through to Lakȟóta elders and knowledge holders.

Though her work is multi-authorial, she emphasises that artificial intelligence is not a collaborator, but a vessel, instrument or other kind of conduit. Recent news has fuelled the image of artificial intelligence as an unstoppable, opaque, deitylike force of technocapitalist acceleration. As an aesthetic, it conjures up uncannily smooth, slick ‘slop’ that litters the internet. Its newness to the cultural lexicon, its vague threats to render our livelihoods inert and its ubiquity all contribute to public overwhelm and suspicion. But here, in Kite’s hands, this technology is capable of exchanging poetry, singing songs and making art that abides by Indigenous research ethics. Kite’s insistence on ethical use, guided by Indigenous protocols and her animating of materials reminds us that these technologies are not omnipotent totalising forces, but a series of inputs and outputs dictated by a combination of human and nonhuman agencies. It is a process that is both overwhelmingly complex to comprehend and simple to observe on a material level. Kite’s interactive sculpture Ínyan Iyé (Telling Rock) (2019) includes a wide range of materials listed as ‘song, power, sound, processors, machine learning decisions, handmade circuitry, gold, silver, copper, aluminum, silicon, and fiberglass’. Here, several hair-braids are connected together to be handled by the viewer in a collaboration between supposedly ‘inert’ materials and the forces that animate us humans. Abstract concepts like ‘machine learning decisions’ are made tangible – made real – through Kite’s insistence on their materiality and our physical manipulation of them. Recalling her performance Pȟehín kin líla akhíšoke. (Her hair was heavy.) Kite told me, “The braid became so heavy, and honestly kind of gross, as I swung it around and dragged it across the floor.” Our exchanges in listening and speaking were punctuated by a raucous little laugh to ourselves, which carried throughout the space.

List Projects 31: Kite is on view at MIT’s List Visual Art Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts, through 18 May

Rachel M. Tang is a writer and research fellow at Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.