Nikhil Chopra’s For the Time Being chose an expansive fuzziness over the confrontations that a more explicit manifesto might invite

There’s a buzz around Aspinwall House on the opening weekend of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale (KMB). A growing pool of visitors and workmen swirls around this grand colonial waterfront bungalow – the sometime residence of a ‘coir magnate’ – that serves as the unofficial headquarters for the biennale. The deep foghorn of a passing cargo ship, leaving the historic port of Cochin (now India’s first international container transshipment hub), blends with the whine of power tools and the hum of ambient chants issuing from one or more of the installations or performances at this site. I took it for an inadvertent soundtrack for the butoh dancer Yuko Kaseki who was floating through the premises, but it may have been one of the acapella interludes in Sheba Chachi and Janet Price’s video installation Beauty/Pain (2025), or the ‘polyphonic soundscape’ accompanying Bhasha Chakrabarti’s quilting piece Diasporic Transcriptions (2025).

The sense of intermingling artworks and realities seeping into one another pervades the biennale by happenstance as well as by design. The curator’s note by Nikhil Chopra (along with the collective HH Art Spaces) describes the event as ‘a living ecosystem where each element shares space, time and resources and grows in dialogue with each other’. This edition’s reassuringly contingent title recalls the familiar Hindi motto chalta hai (so it goes/let it be). It’s also a provocation, given that timeliness has been an issue for the festival. The biennale returns three years after the previous edition – itself delayed. The subsequent postponement of this sixth edition was attributed to ‘financial constraints and unavailability of venues’.

As the current edition opened, some of the more ambitious works, such as Bani Abidi and Anupama Kundoo’s Barakah (2025), an arklike community kitchen of Kerala timber and thatch, or Utsa Hazarika’s monumental steel sundial, Yantra (32° N/Horizon) (2025), were still works in progress. The status of Marina Abramović’s video installation Waterfall (2000–03), touted as something of a headliner, was initially a topic of media speculation, opening two days after the inauguration.

Chopra had already invoked a small rosary of other key words in his curatorial vision for KMB: live art, durational work, participatory moments and friendship economies. Like the title of the event, these all suggest a blurring at the edges of the art encounters in Kochi. This was combined with an explicit focus on ‘the body’ – less an individual body than the universal site of refuge and reconciliation. ‘Our bodies are not entirely ours,’ Chopra said.

My own reading of this curatorial manifesto was that Chopra was attempting to genially accommodate the fractious polarisations of global, national and local politics through the self-conscious contingency of ‘for the time being’. Choosing an expansive fuzziness over the confrontations that a more explicit statement might invite. Whether this should be seen as nuance or evasion (or perhaps nuanced evasion), and whether it is a successful strategy, is a verdict that may be clearer by the end of the biennale. Inevitably, KMB retains many of the familiar pathologies of the artworld: the tendency to dress up the artist’s cosmopolitan privilege as exile and displacement; the love for the exegetical; the naive faith in ‘the body’ as a place of universal consensus; the last has already come home to roost as a controversial if relatively harmless irony, as we shall see.

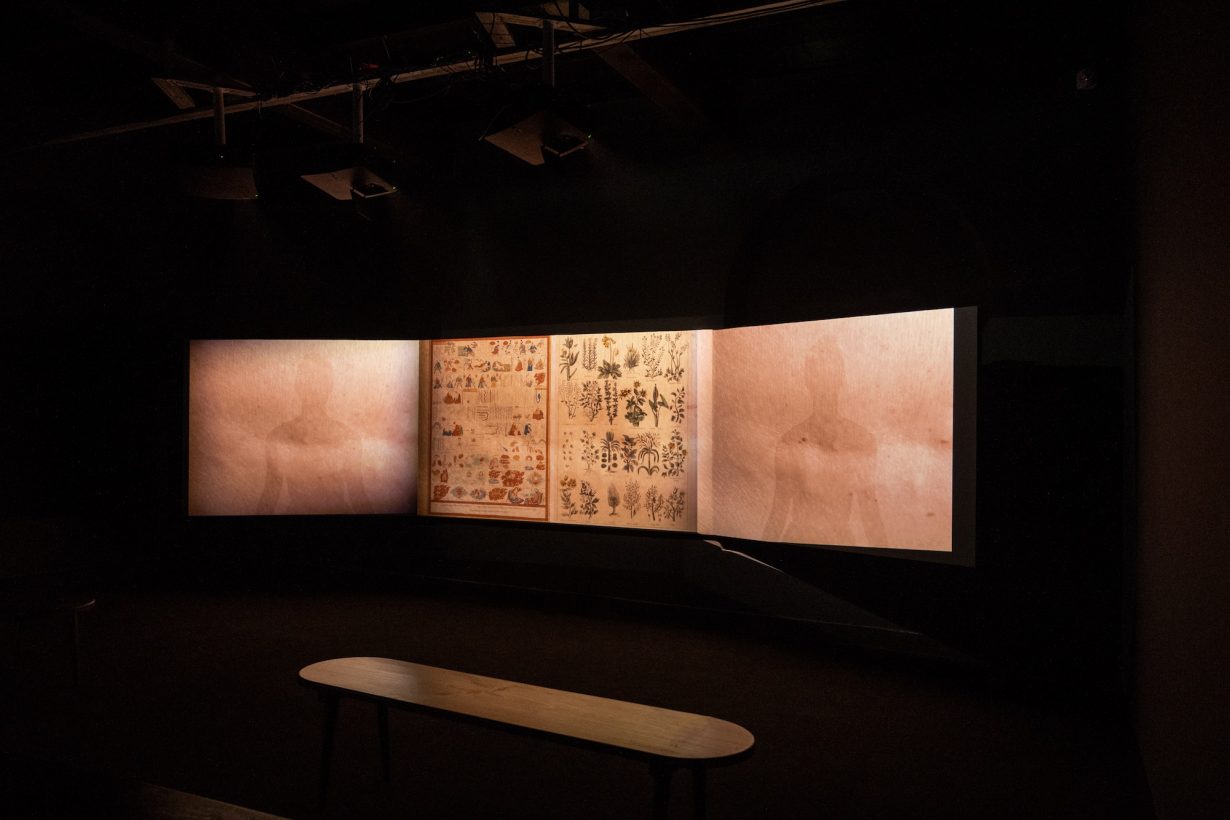

(installation view, Kochi-Muziris Biennale). Courtesy the Kochi Biennale Foundation

I had my favourites among both the largespace installations and the more intimate pieces of performance and of two-dimensional art. At the Anand Warehouse, Ghanaian artist Ibrahim Mahama had installed the latest iteration of his project Parliament of Ghosts (2017–). Mahama’s chamber, draped in recycled gunny sacks and peopled with a throng of reassembled or repaired wooden chairs, offered an imposing and affecting tableau that both evokes and subverts collective memories of Euro-colonial spaces of governance – and the histories of imperial commerce behind their curtains. In a nearby hall, Indian artist Kulpreet Singh’s Indelible Black Marks (2022–24) referenced the farmers’ protests that encircled Delhi in 2020–21 (forcing an uncharacteristic climbdown by the Modi government) and the ongoing air pollution crisis in the Indian capital. It featured a film of the familiar (to a Delhi citizen) fields of flaming rice stubble on which the artist and his collaborators enact an apocalyptic danse macabre, screened amid bleak canvases rubbed with aromatic soot and straw. In its raw materiality, the piece was a particularly effective pairing with Mahama’s installation.

Among other arresting works were Tino Sehgal’s choreography piece (Kiss, 2003) in which a young man and woman snaked balletically (if horizontally) across the floor, their eyes locked in erotic tension, a disconcertingly intimate spectacle in which the viewer is soon a self-conscious intruder. Another corporeal body of work – the Sri Lankan photographer Lionel Wendt’s (1900–44) delicately rendered images of subaltern men’s bodies – was charged with gentle power and eroticism. These beautifully crafted photographs also express a quiet rebuke to the incantations of theory in which so many solidaristic artworks are draped. Wendt’s photographs resonate sympathetically with Not What You Saw (2024–), Keerthana Kunnath’s vibrantly contemporary portraits of South Indian women bodybuilders (part of Edam, a show of artists with roots in Kerala that runs parallel to KMB).

Courtesy the Kochi Biennale Foundation

I had wondered whether Tino Sehgal’s Kiss might provoke an outburst of moral policing, but in the event, it was a painting by a prominent local artist, Tom Vattakuzhy, that provided KMB’s first curatorial crisis. Vattakuzhy is known for finely lit scenes of everyday life rendered with stylised naturalism. However his allegorical Supper at a Nunnery (2016), depicting 12 nuns at a table with a central, bare-breasted female figure (who, the artist maintains, represents Mata Hari), was reproduced in a magazine article on the Edam show and soon decried as offensive by some Christian groups. Some 18 percent of Keralans are Christian, and given the potential repercussions in an election year, the Edam curators and the artist (who happens to be Christian himself) announced that the painting would be withdrawn.

The suspense surrounding the Marina Abramovic´show persisted for some time after we arrived at the Island Warehouse. A gigantic shed of sheet metal, its stark utilitarianism, its nonchalant scale and modernity, are a salutary contrast to the colonial charm and decadent tropicalism of the colonial warehouse venues in Fort Cochin. At the back of the hall was an array of blank screens that finally flickered to life at the appointed hour. Waterfall is a wall of sound – and light – displaying the faces of 108 Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns, all chanting the Heart Sutra. ‘Form is emptiness,’ the Heart Sutra tells us. ‘Emptiness is form.’ The sutra’s ancient wisdom resolves into a foam of white noise that you can absorb in supine comfort from one of the deckchairs arrayed at the foot of this sensory cataract. After a long day’s biennale (17,000 steps, said my fitness app), this was an utterly soothing experience. It was also an uncanny metaphor for the tide of imagery of the biennale itself. As the roar of the swarm onscreen recedes, you are drawn to the individuality of the faces facing you. Some chanting faster than the collective cadence, some more deliberately. A few look back mutely, resolutely evasive. At least for the time being.

Kochi-Muziris Biennale: For the Time Being. Various locations, Kochi, through 31 March.

Read next What Keeps Marina Abramović Going?