The author weaves his personal experiences of New York with the story of World Trade Center architect Minoru Yamasaki in a multifaceted memoir

This is a personable, erudite memoir that ambles through a series of theoretical and historical musings linked to the author’s emotional, intellectual and practical engagement with New York City from 9/11 to sometime shortly before the pandemic. Towards its end, Beal, an artist who had previously studied architecture, quotes from a 1993 interview with Ada Louise Huxtable, the powerful American architecture critic, then approaching the late phase of her career, in which she rues the gradual collapse of optimism in what the built environment can achieve. ‘We truly believed that the horizons of technology, the horizons of art were going to lead us to a better place and make us a better people,’ she says. ‘We found this wasn’t true.’

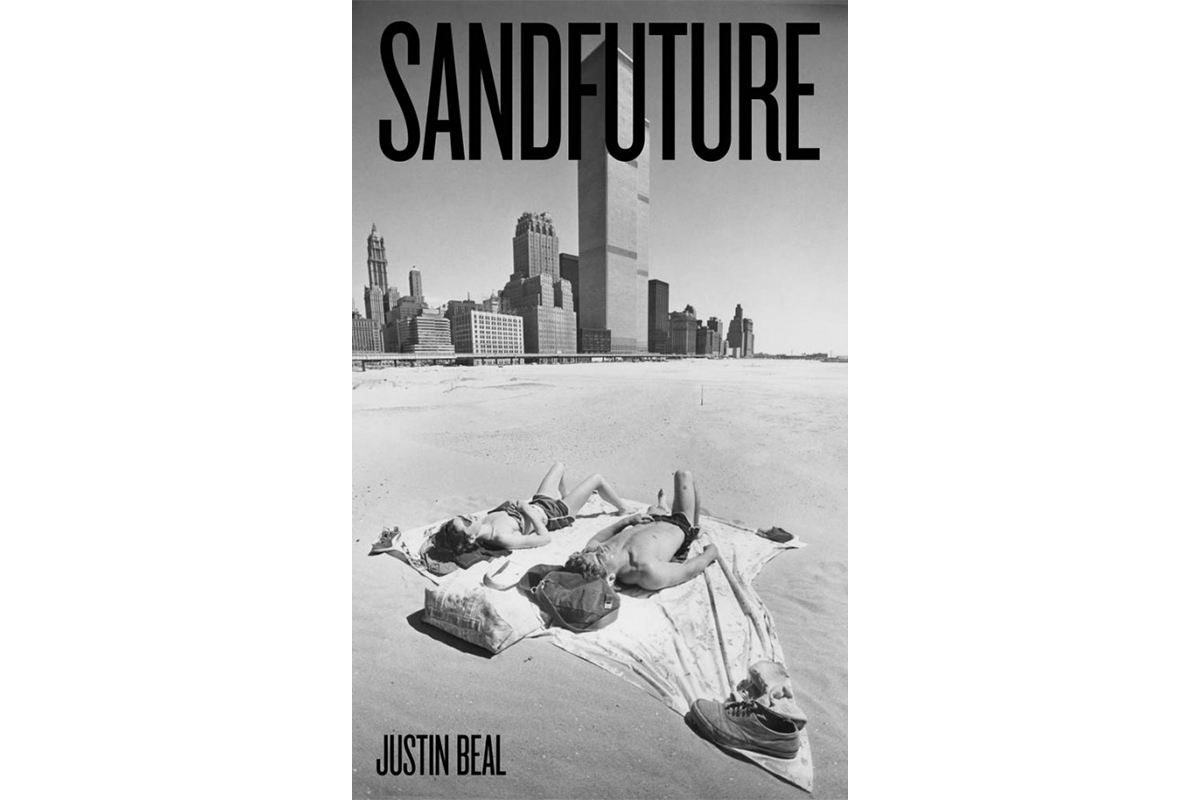

It’s an assessment with obviously broader resonances that Beal examines afresh here, albeit from a different generational standpoint, but nevertheless anchored in contexts that were at the heart of Huxtable’s criticisms. Among the latter is the World Trade Center, the destruction of which occurred 20 years ago this month, and the story of its architect, Minoru Yamasaki, whom Huxtable championed early in his career and essentially renounced late in hers, and around whom much of the book revolves.

Beal writes in short passages that bounce around, stretching the reader’s ability to make connections: a memory of standing in the WTC plaza and looking up at the buildings; an account of Hurricane Sandy’s arrival and inundation of New York’s low-lying areas; a new romantic relationship with a gallerist; a first sighting of a residential tower rising at 432 Park Avenue; a brief history of migraines and their literatures (Joan Didion, Oliver Sacks). Gradually, through repetition and expansion, the main storylines emerge, though the links remain ambiguous, our attention repeatedly pulled away by the distraction of learned asides and well-researched nuggets.

We meet ‘Yama’ the architecture student, also nicknamed Sockeye by fellow students for his gruelling summers spent canning salmon in Alaska, and learn of his rapid professional rise through the war years, his resistance to late modernism, a suspect daintiness in his work, the initial triumph of his design for the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St Louis (the later demolition of which was famously – and slapdashedly, in Beal’s estimation – labelled by architect Charles Jencks as the day modern architecture died), his poor health, the paucity of information about his inner life and, later, the steep decline in his reputation. Nevertheless, it remains a fact that Yamasaki was commissioned to design not one but two of the tallest buildings the planet had ever seen.

Set up in opposition or as a contemporary parallel to the WTC is the story of the Rafael Viñoly-designed 432 Park Avenue (completed in 2015), the tallest example of Manhattan’s new ‘pencil towers’ – ultra-thin, ultra-high residential buildings made possible by aggressive workarounds of zoning restrictions, design innovations and the highly stratified nature of late-capitalist society – which Beal likens to a gnomon telling time across the sundial of Manhattan. Beal is not unaware of how his opposition to this tower, as pithy as it is damning, could be read as a contemporary equivalent to the bitter objections that greeted the construction of the WTC.

This informative and empathetic text, dense with lightly worn histories (modernist architecture, hospitals, disease, pharmaceuticals, the Port Authority, the economics of the midsize art-gallery), operates in multiple personal registers as well, from Beal’s accounts of falling in love to becoming a father. It suggests a lively daily writing practice occurring alongside his teaching and artmaking, as well as the embodied belief that, for better or worse, we are powerfully affected by the built environment. Rather than directly answering Huxtable’s pessimistic assessment, Beal seems to want to acknowledge it and move on.

Sandfuture, by Justin Beal, published by MIT Press