In The Substance, it’s old versus young; hot versus not; Demi Moore versus Margaret Qualley; the film versus its viewer – and no one wins

A body-horror satire that ostensibly takes aim at ageist beauty standards, writer-director Coralie Fargeat’s sophomore film The Substance casts a staggeringly gorgeous sixtysomething Demi Moore as a former Oscar winner named, insanely, ‘Elisabeth Sparkle’. Elisabeth has recently been fired from her network television job teaching on-air aerobics, after committing the unthinkable sin of turning fifty. On seeing a billboard of her face being torn down at the roadside, Elisabeth crashes her car and winds up in hospital, where a suspiciously modelesque male nurse slips a USB stick marked ‘THE SUBSTANCE’ into the pocket of her coat. (There is also a note: ‘It changed my life.’ The phrase ‘for the better’ is conspicuously absent.) When she plugs in the drive, she discovers that the Substance is an injectable serum, capable of splitting human DNA into two parts and allowing a new self – a younger, more fuckable self – to emerge from the body of the user. The original host, called the ‘matrix’, and the second self, called the ‘other’, are required to cut their time in half exactly: one week each, on rotation. The two halves do not share any memories or experiences; they can never be awake at the same time. They must sustain themselves, or ‘stabilise’, by drinking each other’s spinal fluid every day, or they will begin to bleed from the nose, and then disintegrate completely.

The treatment is, in other words, a frightening prospect, but perhaps not that much more unsettling than some of the work that real-life celebrities must undertake in order to retain their youthful glow. When Elisabeth embraces the procedure, which she executes at home in a white-tiled bathroom that suggests a chic reboot of Saw, a girl named Sue (Margaret Qualley) emerges from her spine. As promised, she is farcically perky. Seeing an ad in the paper for Elisabeth’s old job, Sue auditions and succeeds on the strength of her sexy baby affect and the undeniable perfection of her body. Soon, she becomes a star, and the weeks she spends awake are a whirlwind of Vogue shoots and late-night talk-show appearances. Elisabeth, meanwhile, spends all her allotted days hiding out in her apartment: a sad, shuffling recluse who sits in front of the shopping channel for so long every day that her ass has left a dent in the armchair. (Any questions the audience might have about her ass are, incidentally, answered by a lingering shot of it unclothed, which is included for the benefit of demonstrating that it sags a little in comparison with Sue’s.) What Elisabeth is getting out of this arrangement is not entirely clear, given that she experiences none of Sue’s successes, and the toxic bond between them starts to seem less and less as if they’re two halves of a whole, and more like that of a mother, and the bratty, pretty daughter she envies and admires in equal measure.

The procedure – as procedures tend to do in body-horror films – goes wrong, and Sue begins to steal more waking hours by draining additional fluid from the unconscious Elisabeth. As Sue’s world expands, Elisabeth’s contracts, and she ages at warp speed. Now, Moore is put in prosthetics to mimic papery skin; outrageously pendulous breasts; bulging, osteoporotic joints. As with the titular serum’s requirement that the user split their time between both bodies, the film seems to split its aesthetic depending which actress is onscreen: it is half hagsploitation movie, half that one Benny Benassi music video where the oiled-up women play with tools. That hot, twentysomething people are sexy is not news, and if The Substance had been sold to me as pure exploitation, its infatuation with Qualley’s glistening (also prosthetic) breasts and butt would be easier to swallow. Couple this infatuation, however, with the way that it uses Elisabeth’s rapid descent into old age as a kind of jump-scare, and things start to look a little murky, message-wise. A colossal photograph of Elisabeth in her ‘prime’ is the centrepiece of her minimalist apartment, meaning that Fargeat often shoots Moore sitting in front of an image that is Photoshopped to look like the smooth-skinned ghost of her 1990s self. Does she mean to ask us to compare them? If she does, is this an especially feminist thing to do? Again, I am asking these questions not because I am a killjoy who cannot appreciate sexiness or subversion for their own sakes, but because The Substance is presenting itself as a movie with provocative new ideas to impart, and for an onscreen examination of a toxic trope to feel actually subversive – as opposed to toxic, but now with an implied wink – it is not quite enough for that trope to simply be reflected back to us at an exaggerated scale, as if in a funhouse mirror. If Fargeat, a distinctive visual stylist with an obvious interest in grappling with ideas around gender and violence, wants us to interpret her film as commentary in addition to enjoying it as a body-horror romp, I would argue that it is a mark of critical respect to subject it to a thorough examination – to ask what it means to tell us, exactly, about the experience of being both middle-aged and female.

By the time the film approaches the two-hour mark, Elisabeth has transformed into a bald, misshapen crone, and Sue has unceremoniously kicked her to death. (Long live the new flesh, indeed.) At this point, The Substance slips into hysterical hyperdrive, and the change in tone is not unwelcome: Sue has been chosen to present the TV network’s New Years’ Eve show, but with Elisabeth dead, she has no fluid left with which to stabilise herself. She decides to go against the rules and enact the original Substance procedure again. Rather than a newer, better Sue emerging from her fully-formed, she is transformed into a lumpy, many-limbed, multi-mouthed Sue-Elisabeth hybrid. The creature, with Sue’s blue gown draped in tatters on her body, takes to the stage at the New Years’ special, where the scene culminates in a literally explosive splatterfest that evokes late-80s Peter Jackson, or the climax of Brian Yuzna’s 1989 film Society.

I had no doubt that Fargeat was having fun at this point, and I was having fun, too, and I wondered whether I’d been wrong to assume that this film was ‘about’ anything serious at all. And yet: the final shot seems to cry out for analysis. Elisabeth, now simply depicted as Demi Moore’s face atop a heap of wriggling tentacles, drags herself onto her star on the Walk of Fame to die. As she does, she dissolves into slush, and a street sweeper cleans her up like garbage. Her vanity has made her desperate, then monstrous, and then a fatality. It is a vivid image, and one that scans as several things at once: nihilistic, tragic, darkly comic, and perhaps even – whisper it – a touch misogynistic.

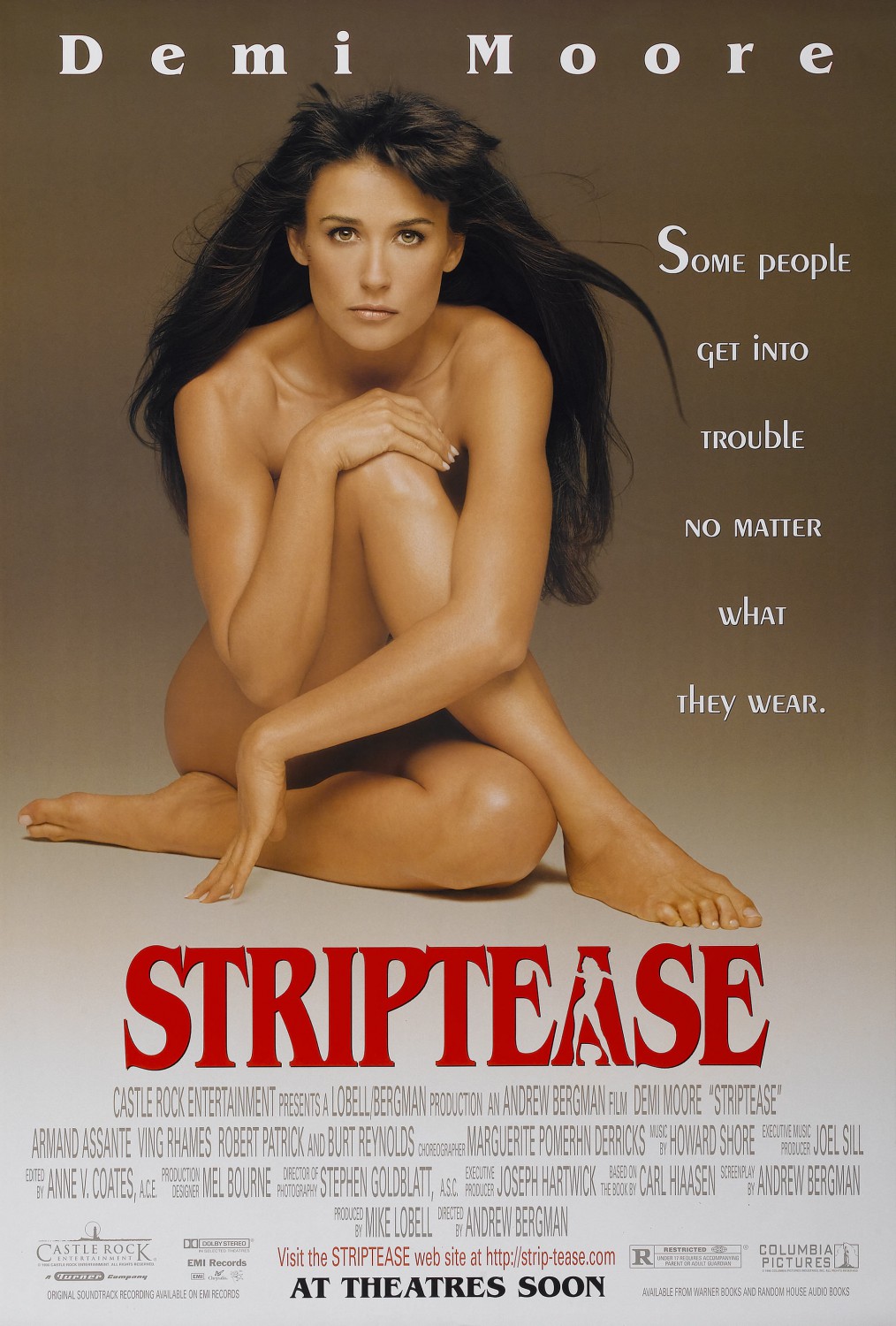

Describing Moore’s performance in The Substance as ‘fearless’, as many critics have, makes sense: she is terrific in the film, and the intelligence she brings to the role gives Elisabeth a necessary dignity that’s sometimes absent from the script. It is worth noting, though, that one of the fears she is being asked to face is that of appearing old, and the bravery implicit in her willingness to do so is reliant on the assumption that ageing is gross and absurd – a thing best done in private, and ideally not at all. If we say that Moore is ‘in on the joke’, we must admit that at least part of the joke is: ‘Demi Moore is older than she used to be.’ In 1996, when the much-maligned film Striptease was released, I was eight, and I vividly remember seeing Moore for the first time on the VHS cover: fully nude, staring straight into the lens. I did not know then, of course, that Moore had earned the nickname ‘Gimmie Moore’ for demanding to be paid $12.5 million for the role, which was at that time the highest fee ever commanded by an actress. I did not know either that by the time Striptease was released, she was 34 years old, and that if she’d asked for a huge payout it was probably not because she was, as the papers claimed, a ‘super-diva’, but because she knew that the industry might not see her naked body as extraordinarily valuable forever. Being Demi Moore has always taken work, and it is a job that she has executed with great strategy and skill. I would not say that the graft she has put into staying fit and gorgeous makes her monstrous or tragic. I would say that it makes her a very smart woman who is gaming a monstrous, tragic system as best as she can, in the same way that asking for $12.5 million before taking off her clothes did back in 1996.

Now, I myself am a couple of years older than Moore was when Striptease was released, and although I’ve no idea what it is like to age as a beautiful celebrity, I do have a decent idea of what it’s like to age as a regular woman. I can’t emphasise enough the number of hours I have wasted feeling frantic about some new flaw I have noticed on my body, and obsessing over how to fix it. I wonder fairly often how much more room I would have in my head to form interesting thoughts if so much space weren’t taken up by all this self-hating shit, and as I watched The Substance and absorbed its ‘satirical’ suggestion that being old and female is hell – its implication that grey hairs and liver spots are monster-movie repulsive, but the body of a twentysomething girl deserves our slavering attention – I simply thought to myself, well, there’s another 140 minutes of my life I’ve spent considering that.

I presume I will be told, as I was in the glory days of Promising Young Woman’s (2020) rapturous post-festival reception, that the things that feel to me like expressions of internalised misogyny in the film are actually there to comment on internalised misogyny. Well, perhaps so. Still, since I myself am not a new-to-the-world sexy baby a la Sue, I am already aware that depiction and endorsement are two different things, and even armed with this knowledge, I find myself somewhat dissatisfied here. I do not need a satire to provide me with answers as to how I ought to live, or think, or age. I do require it to do something other than cheekily reproduce the awful status quo, however stylishly it does so. By all means, gimmie Moore – but I beg you, give me substance, too.

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norfolk. Her latest book is Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object (2024)