John Rogers, showing at the Brent Biennial, on how psychogeography gives power to the people

John Rogers has produced an audio portrait of the area surrounding Kensal Rise Library, which people can download from signage outside the library, and that unfolds as a series of interviews with locals which draw on their memories of the changing streets and communities.

John Rogers is an artist, filmmaker and author of This Other London – adventures in the overlooked city. He directed the feature documentaries The London Perambulator (2009), Make Your Own Damn Art – the world of Bob and Roberta Smith (2012), London Overground (2016) and In the Shadow of the Shard (2018). He produced and copresented the popular Resonance FM radio show and podcast on walking, Ventures and Adventures in Topography. He also produces a regular series of walking videos on his YouTube channel.

ArtReview Tell us more about the work for the Brent Biennial.

John Rogers It’s a geographic sound map or trail of Kensal Rise. The form the project takes has partly been informed by the COVID-19 restrictions. I had planned this beautiful archive inside the library and some of the sound works were going to be burnt onto vinyl which could be listened to within a listening booth. We’ve not got those, but its ok, those were outcomes, they weren’t really the work itself which is a portrait of the community in their own words. By ‘community’ I mean the community of the library. Where it becomes geographic is that the emphasis is on the subjective responses to the environment and the changes within that environment rather than looking for some objective, dry, historical overview of the area, or even contemporary commentary on the area.

If you look up Kensal Rise, a lot of the narrative surrounding the area is around its recent gentrification, how people have moved in from Notting Hill or how it is the ‘new’ Notting Hill. And within those narratives the voices of the people who have lived there a while tend to be forgotten or overshadowed. When you have periods of rapid change it’s very easy for those narratives to get buried under estate agent chatter.

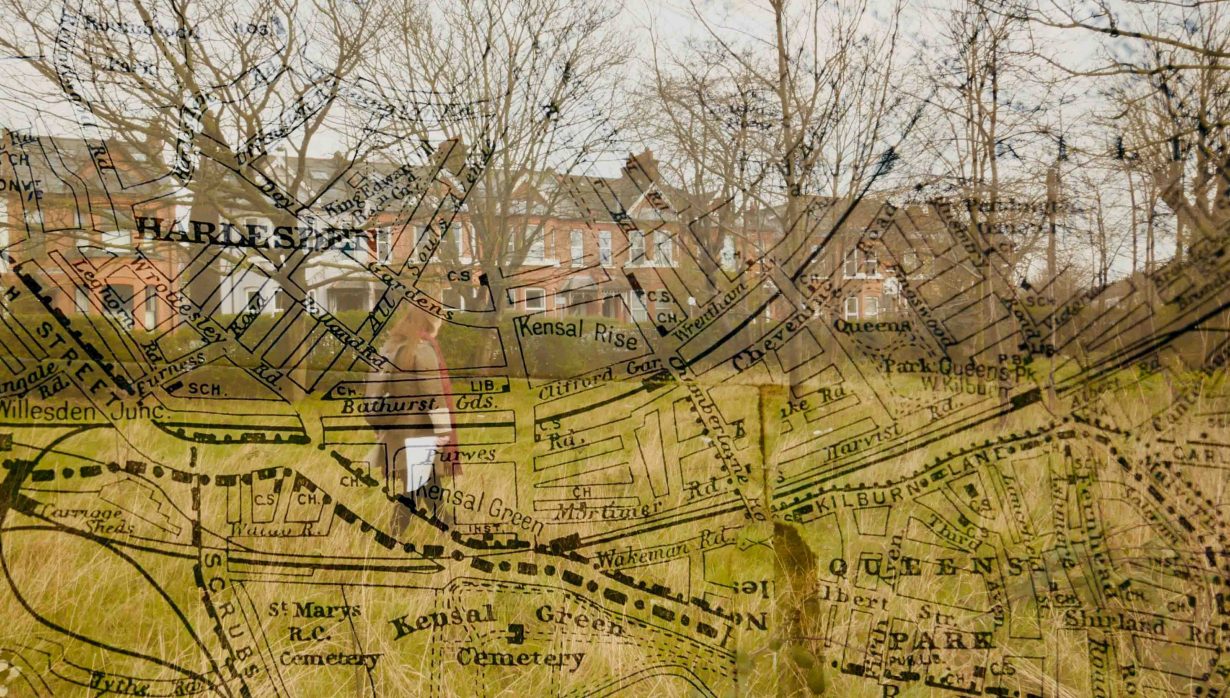

Originally, I wanted everyone to take me out for a walk and I recorded many like that, but then others are sit-down interviews for practicality, if the subject is older or because of the elements. What would really open it up I realised is giving people a map of the area dating from the 1920s. Some areas of London, if you look at a century-old map, the layout is relatively similar. In Kensal Rise the basic triangle is there but mostly it’s radically different. So everyone took that map and gave their own subjective response to it.

AR And who did you interview?

JR A whole range. The youngest person was probably in her early twenties, the oldest was a ninety-year-old lady who moved into a street that was newly built on fields and everything beyond was still open land. She has very vivid memories of the war obviously as well.

AR Have you used maps as a trigger before?

JR I use maps all the time actually. Maps contain multiple stories. It’s a provocation and an invitation to explore. On a project like this my first stop tends to be to the local archives – before I speak to anyone – where I will dig out an old map and overlay it onto a current one. In doing so, I’m looking for the contours of tension within the landscape. I will push at those contours, explore them and see what comes from that. There were much older maps: if you look at a 1860 map of Kensal Rise there isn’t really much there to be honest, the development comes after. Some of that farmland was there right up to the 1950s and 60s.

AR How did you become interested in psychogeography?

JR I came across the term, as a situationist expression, through music journalism. I was a kid reading about punk, post-punk, and back then – it seems a bit dead now – people wrote about music in terms of cultural theory. I’ve also always been interested in walking, in the environment. I grew up in the Chilterns where I walked a lot with my dad, and I travelled a lot in my twenties. Walking was always the way I connected with a place.

I had been living in Australia for a year and when I came back, my hometown, High Wycombe, was undergoing a period of redevelopment. They were tearing the guts out of the town, but how do you articulate that? The council and the planners had all their metrics about how they were going to redevelop the town: traffic flow, yield per square metre and the like. How do we respond to data? Psychography seemed to provide a set of tools which allowed people to respond to the environment and the proposed changes. This was around 2004–5 and I got a grant from the arts council to make Remapping High Wycombe.

AR Is the context of the library relevant?

JR The ethos of the Kensal Rise Library is at the heart of the project. About 60 percent of the contributors are connected to the library, as users or in some other way. You can’t listen to any of the clips without feeling the presence of the library. It had a very high-profile campaign to save it; the people who run it are campaigners with a passion for it. Margaret, one of the voices you can hear in the work, runs an under-five club but also devotes most of her spare time to the place and was heavily involved in previous campaigns supporting it too. In fact, one of the stories I was keen to get down is about the older campaigns. You can read about the most recent one in The Guardian because it had loads of celebrities involved or whatever, but the campaign from 1980 has sort of been lost in that noise.

It was also important of course to reflect the diversity of the community: there’s people in £2 million houses living across from people renting from housing associations. Those narratives needed to come to the surface too.

AR Is there a tension?

JR No actually, not in terms of walking the streets day-to-day. People embrace the change, but I think there’s a need to acknowledge the communities who have lived there all their lives. Communities have dispersed from the area, that has to be acknowledged: this area used to have a very strong African-Caribbean community for example, a very strong Jewish community, which is not so much the case now. One interviewee recalled that there used to be five synagogues in the area and all but one has now gone. One guy I spoke to went to a Jewish school at one of them, which is now an ugly block of flats. He is actually the nephew of Leon Kossoff, who spent a lot of time in Kensal Rise and even painted it. This all comes from reading the map.