Yiadom-Boakye’s new paintings at Corvi-Mora explore a dialectic between expression and enigma

In a largescale oil painting, a man holds the skull of a magpie aloft, elbow cocked to bring the bone level with his eyeline. Below his feet, a row of semicircles in green and white decorate the frame like footlights. Behind, or perhaps upstage, another man limbers up, his arms flexed and pulled together by interlocked fingers. The backdrop is a wash of golden brown, blotted by dry black shadows in illogical patterns – an expressive non-space. We view An Oracle In Flight (2024) with bated breath. What might one thespian say? What movement does the other prepare? In Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s paintings, the world’s a silent, disquieting stage.

Indeed, Yiadom-Boakye’s new exhibition of oil paintings and charcoal paperworks explores a kind of dialectic, between expression and enigma. In No Capital To Sing For (2024), two Black women sit facing one another, legs outstretched but propped upright as if leaning against the edges of the canvas. One lifts her arm to the other in a kind of port de bras, her index finger extended to a point. Above, familiar golden textures hang like soupy mist. We aren’t necessarily allowed in – and Yiadom-Boakye gives little context; only cryptic titles and a mystical poem in place of an exhibition text.

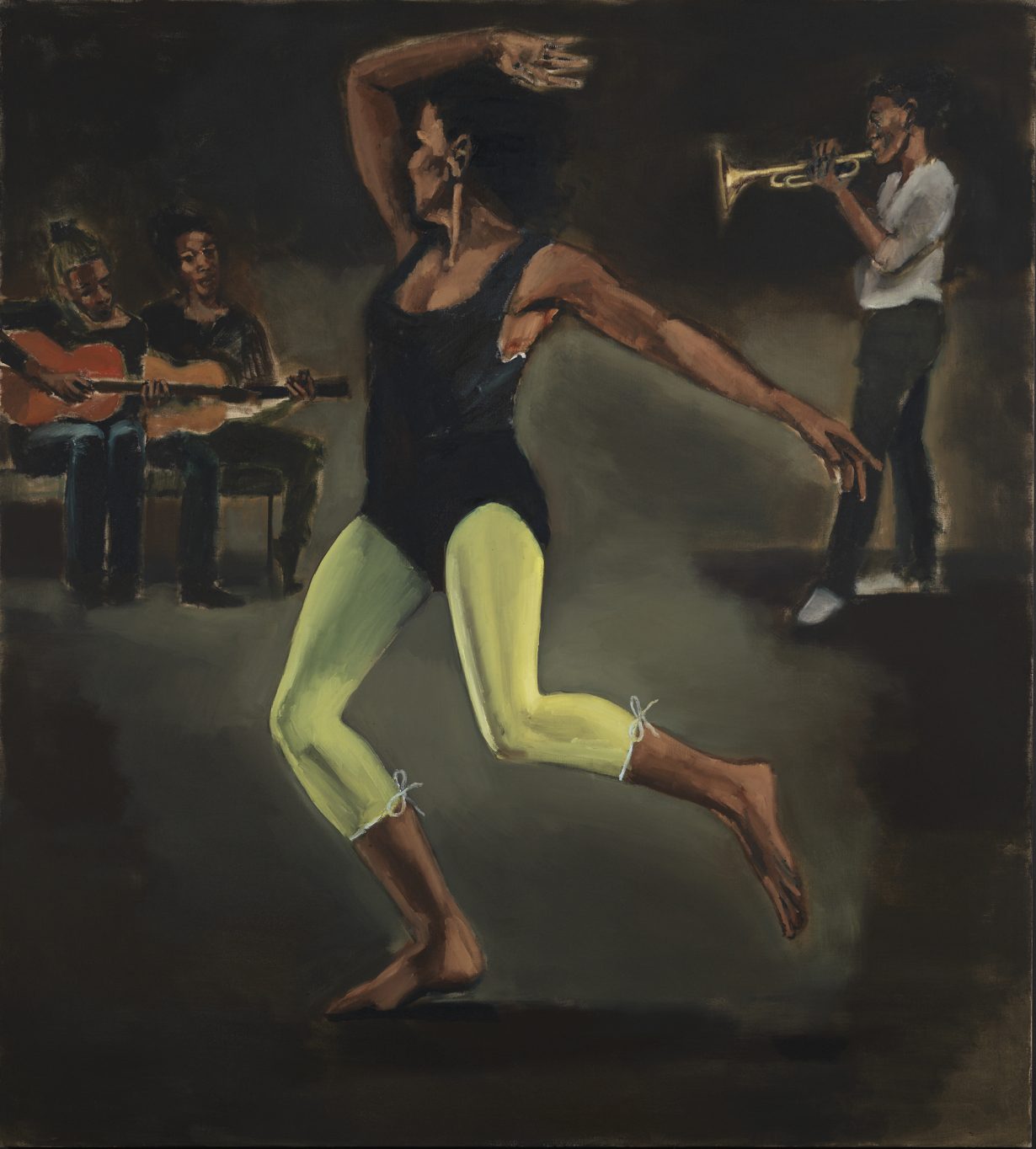

The activities we see in Keep The Moon Amongst Ourselves often suggest forms of performance, allowing Yiadom-Boakye’s characters a world unto themselves, an introspection mirrored by her sparse, dark compositions, and a silent language of the body. In A Herald In Spring (2024), a woman dances to a trio of musicians. Her leggings, tapered into a delicate bow at the hem, are a radiant lime-green – brave and forthright as her movement, on unapologetic display. Many of the artist’s subjects wear tight white garments – like leotards or base layers. Yet, in places, the dry white paint overflows. One figure’s hand is smudged by it; another’s wears it like a glove; in Vernacular Warnings (2024), a trouser hem seems to disappear as white strokes run down a figure’s dangling foot. This absurd injection of the artist into their painted world is disarming. In the exhibition’s dreamlike logic, skin is something a painter, well, paints the colour of. Something we choose and define, for ourselves. Fiction, performance – they’re all about artifice, and the world we might create when we’re experiencing it differently, not living immediately in its present moment.

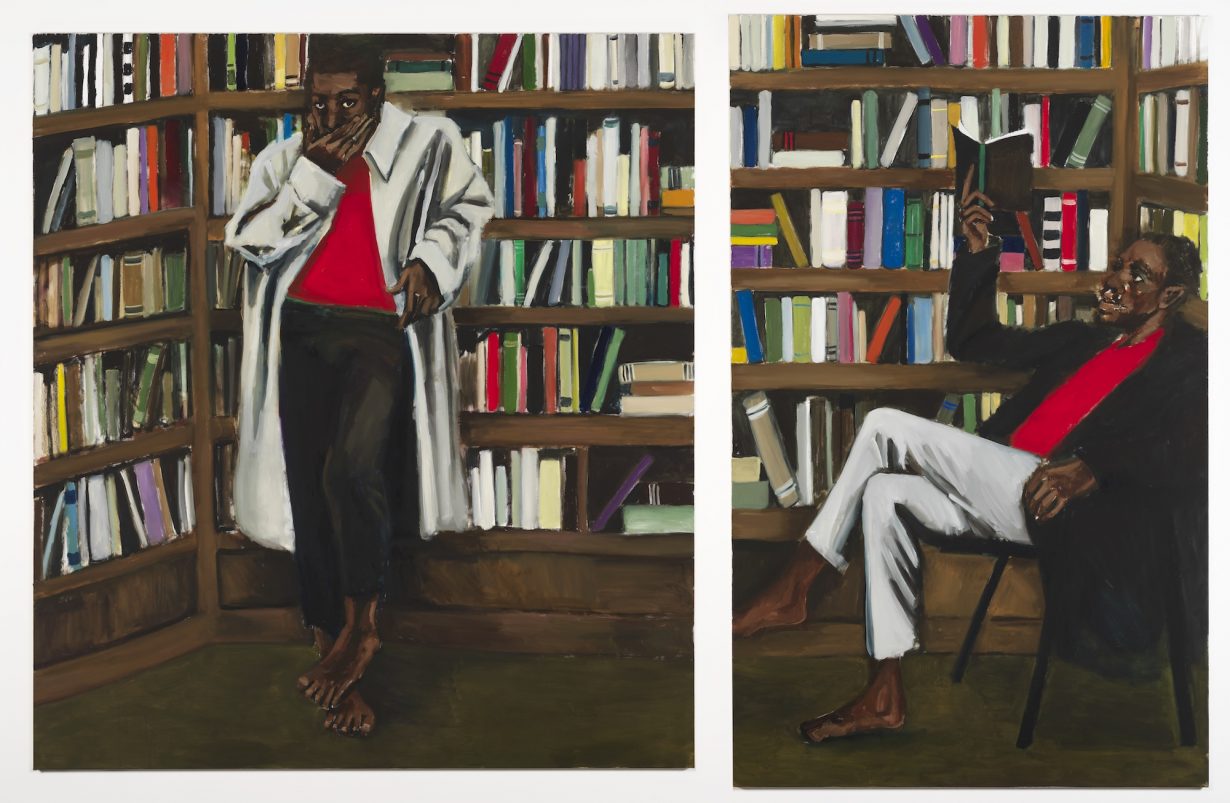

In this world, gazes are important. In A Herald In Spring (2024), the dancer’s face is whipped away from the viewer – perhaps spotting in pirouette, or following her musicians, but certainly uninterested in our scrutiny. In the charcoal work The Maximum (2024), a male figure stands in profile, looking off beyond the frame’s edge; with aggressive markings and large swathes of untouched paper, it presents like a negative of the oil paintings. A sense of melancholy is never far from Yiadom-Boakye’s work, a loneliness that unknowability can also engender. In fact, it’s a rather modernist sensibility which she enacts with art historical acuity: there’s much of Goya’s dark vision of the world in a void, or the melancholic individualism of Manet, another great painter of self-consciousness. And so her characters, evenly spaced around the rectangular gallery, surrounding the viewer, only truly feel in communion with each other, not us. A figure leaning against a bookcase in the diptych The Spine, The Spleen And The Reason (2025), in a greyish trench coat with ripples textured like brushed marble, looks at the viewer and holds a hand to their mouth. Perhaps they’re sniggering in secret, or gasping at the sight of us. Perhaps they know something we don’t.

Keep The Moon Amongst Ourselves at Corvi-Mora, London, through 1 March

From the March 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.