Singapore Art Week celebrates its tenth outing – reviewed

Now in its tenth year, the annual Singapore Art Week (SAW) has grown ever more far-reaching, extending its presence to the island’s farthest nooks. Malls, a hawker centre, shophouses and even a holiday chalet have been transformed into art venues, with more than 130 events happening over two weeks. Such dogged persistence is cheering, to say the least, in the uncertain twilight zone of COVID-19 endemism in Singapore. The country is operational but in a tense and watchful way, with restrictions on dining out and private gatherings that may or may not be tightened as the country braces for the Omicron wave. In the past week, daily COVID-19 infections have reached the four-digits, and the state is officially gearing up for a 25,000 daily case load in the weeks ahead…

But SAW continues! Without a marquee event or overarching theme, it is remarkably diverse in focus, with in-person and digital events, exhibitions, talks and screenings. Thematically, there were several clusters of recurring ideas. These include explorations of the affective realm (there were shows about happiness and affirmative unhappiness), Gen-Z urban culture (music, street art, fashion), as well as the inevitable environmental focus, with artists exploring how to co-exist with different species amid climate exigencies.

Where to start? Well, most people began their tour at the newly minted arts cluster in Tanjong Pagar Distripark, an industrial area near Keppel Harbour in the south of Singapore, which explained the snaking queues for entry over the last two weekends. Thanks to the Singapore Art Museum (SAM) moving in late last year, the distripark is becoming cool again. The area used to house arts tenants like Valentine Willie Fine Art and Ikkan Art Gallery, but these galleries moved out over the past decade due to dwindling business and footfall. Now, a new crop of businesses have moved in, including 39+ Arts Space (which is, incidentally, showing a very relaxing installation of sunrises and sunsets by Mit Jai Inn).

SAM’s three exhibitions include Refuse (all exhibitions 2022), a multidisciplinary show by experimental music collective The Observatory that explores mushrooms and fungal growth as metaphors for the group’s entanglements with other media. The pace picks up in Korakrit Arunanondchai’s post-apocalyptic exhibition, A Machine Boosting Energy into the Universe. Here, you will find paint-splattered mannequins in ripped clothes, a naga made from electric cables winding around a scaffolding structure, and blue tie-dye cushions from which to watch his video, Painting with history in a room filled with people with funny names 3 (2015-16). Arguably the apotheosis of the Krit universe, A Machine Boosting… provides a sustained and satisfying exploration of the porousness between human, machine and the divine.

At the distripark, there were also four open-call exhibitions by young curators. The most conceptually assured was Bad Imitation, curated by Berny Tan and Daniel Chong and revolving around the idea of copying, which includes a broad range of artistic strategies that range from faithful miniaturisations to deliberate corruptions of source material. In her series Twice As Far Away (all works 2021 unless otherwise stated), Catherine Hu makes half-sized replicas of the wooden benches and blue-tiled tables found in Singapore’s public areas. These end up being surprisingly tender tributes to Singapore’s overlooked public furniture. Also celebrating common areas in Singapore’s housing estates is Khairullah Rahim and Nghia Phung’s joint work, after-party. Here, the inspiration is the cheap and cheerful furniture abandoned or deliberately left outdoors by residents in working-class neighbourhoods. These pieces of furniture are often adapted into makeshift lounge or recreational areas. Gathering these objects together, Khairullah and Phung’s joyous installation implies an idealised gathering point that is still haunted by the spectre of police surveillance, which happens in most public spaces in Singapore. Discarded construction hardhats and Anchor Beer cans allude to the proletarian at rest and play. But someone is always watching. Perched on a baby highchair, on the seat of an exercise machine and next to a gas canister are CCTV cameras.

Several doors down is the fourth edition of SEA Focus, the boutique art fair curated by Joyce Toh and styled as a free-flowing exhibition with no individual booths. The theme of ‘chance… constellations’, exploring connections in Southeast Asia amid a chaotic world, is a broad church. On show, for example, are Moses Tan’s flesh-coloured phallic sculptures decorated with dainty chains and pearls and Khvay Samnang’s photographic portraits of a dancer donning ritualistic animal masks developed with the indigenous Chong community from Cambodia’s Areng Valley, where a planned hydro-dam threatens their homes and livelihoods.

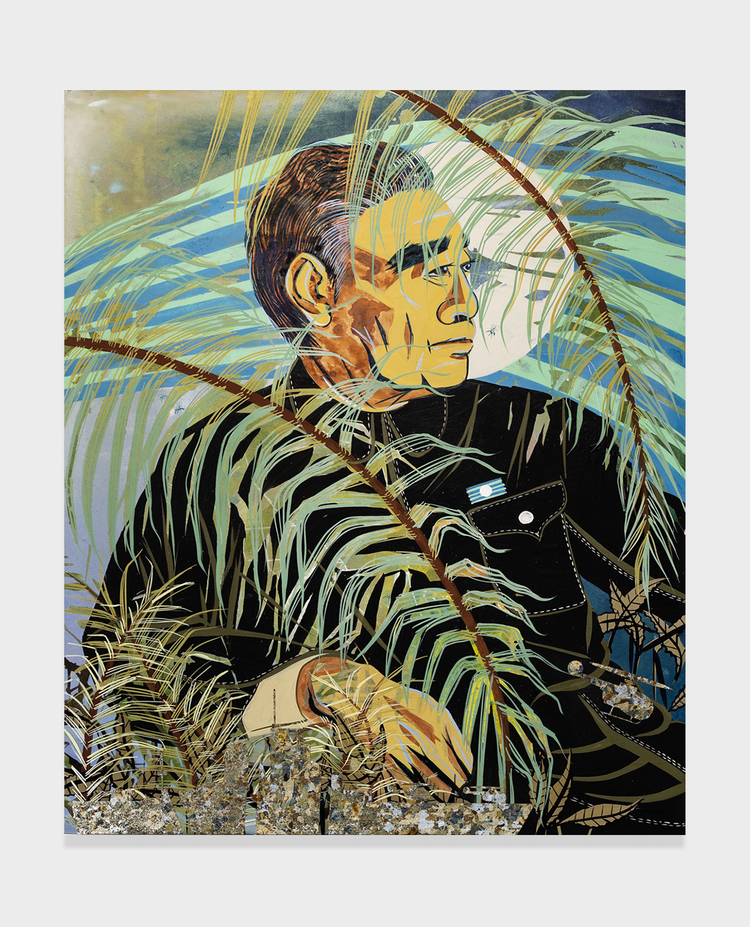

An intriguing discovery for me was the work of US-based artist Tammy Nguyen, presented by Tropical Futures Institute from Cebu. She is showing four paintings from a body of work themed around ‘Forest City’, a failed, catastrophically underpopulated mega development project in Malaysia. In Nguyen’s work, Forest City has become a speculative nation around which she creates images that play on ideas of utopia, hubris and failure. On show are paintings of four historical characters she casts as the military leaders of Forest City, depicted in languid movie star poses amid tropical foliage. These were key figures in 1955’s Bandung Conference: Zhou Enlai, Premier of China, Carlos Peña Romulo, the Secretary of Foreign Affairs of the Philippines, as well as Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru, prime ministers of Egypt and India. The Conference was convened to oppose colonialism and represented a moment of solidarity among what was then called Third World nations. In Nguyen’s work, the four men are the charismatic heroes of an idealised sovereign state; but the paintings’ air of bygone glamour reminds us that the set-up remains firmly in the realm of aspirational fantasy.

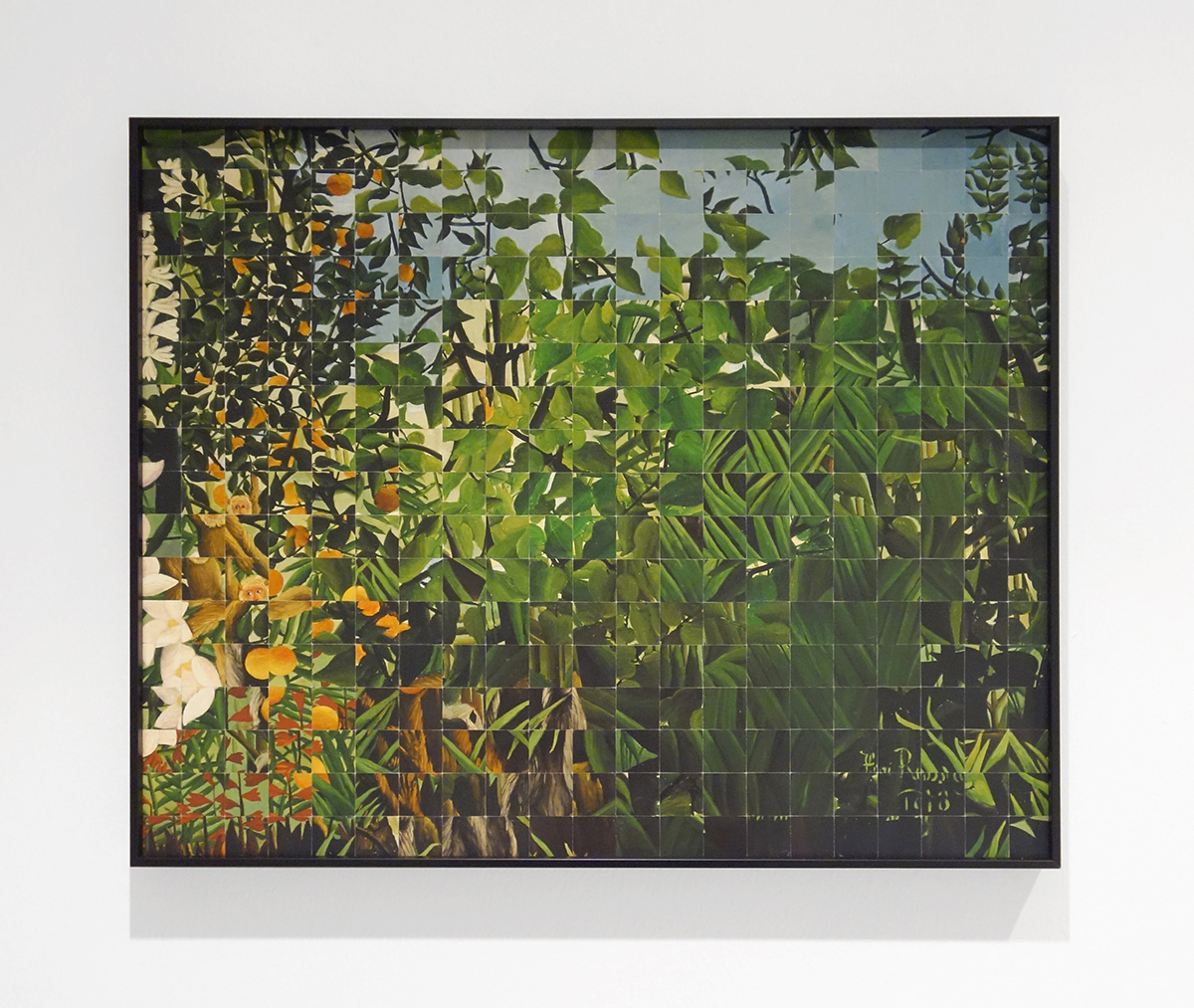

Over at Gillman Barracks, festivities were also in full swing. Nature takes over. In Fost Gallery’s Somewhere Else: The Forest Reimagined, Donna Ong appropriates and subverts representations of tropical forests in the media, advertising and the military, creating works that explore notions of camouflage and unknowability. Images of tropical jungles from nearly four decades’ worth of issues of National Geographic are cut out and collaged into huge greenish prints that look like a camouflage pattern from afar (Tropical Shades: Rainforest Narratives from the National Geographic 1980 – 2019). In another series, she isolates the four colours used in the camouflage print of the Singapore Armed Forces uniform and tiles them into grids (Four Colours Make a Forest, 2017), further abstracting an abstracted pattern. And NTU Centre of Contemporary Art’s Free Jazz IV. Geomancers programming brings together film screenings and performances that explore planetary intelligence and awareness, including Katie Patersen’s incense burning ritual using specially concocted scents inspired by the imagined smells of Earth’s ‘first and last forests’.

SAW officially closes on Jan 23, but most of the exhibitions and programmes run on longer. Somewhere in Bedok blooms the blushing rouge of embroidered roses is hosted in artist-collector Johann MF’s flat, and provides an interesting tension between art and its surroundings. As suggested by the grandiose title, the space is a lot – decorated in chinoiserie, chintz, antiques and gilded fixtures. Against this high visual drama, a group of artist-friends create works in response to the theme of the Freudian unheimlich, including Masuri Mazlan’s Swarovski-studded tentacle-like sculptures that snake around a collection of Chinese and European china.

An interesting pairing of solo exhibitions is Proximities at Objectifs and l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$ at Yeo Workshop, which both deal with Malay identity. Proximities features Zulkhairi Zulkiflee’s probings into the racialised Malay male body, inspired by the trope of the bare-bottomed Malay boy in Singapore pioneer artist Cheong Soo Pieng’s works. The video contains a mix of critical discussion of the trope interspersed with footage of contemporary Malay men and their self-portrayals. Fyerool Darma’s l♠nd$¢♠pΞ$ is a riotous exploration of Malay textiles that straddles both the physical and digital worlds. Internet stock images of songket (traditional woven material) are blown up and stuck onto walls haphazardly, like bad wallpaper. The shapes of palm trees – evocative of Southeast Asia or more generally, the tropics – are cut out from them. Hanging throughout are fabric scraps and actual weavings inspired by the blurred colours of poor source images. Together they constitute a kind of half-ruined cultural ‘landscape’ informed by clichés and internet imagery of dubious lineage, and an artist impishly trying his hand at making sense of it all.

SAW, in its tenth year, has come a long way. It began in 2013 as a state-sponsored cheerleading event for Art Stage Singapore, and whose aim was to capitalise on international art tourists passing through. But SAW has since grown into its own. For one, it survived Art Stage, which went on a steady decline until its abrupt cancellation in 2019. It also survived COVID-19, moving into digital and hybrid formats last year. Now, as nobody’s side show, SAW has ballooned in its number of events and venues, attesting to a resilient art scene that sees commercial galleries and independent, self-initiated projects coming together for a celebratory two-week festival, international tourism be damned. As a result, SAW has become the kind of lovable and frustrating monster festival that locals complain about being unable to finish – which, given the circumstances, is not a bad problem to have indeed.