Tippett’s infernal new film, thirty years in the making, is the culmination of an aesthetic that has transformed cinema – but may well be left behind

Artistic depictions of hell tend to focus not just on its horrors but also its infernal logic. In Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), it is the realm where the proud rebel angels are punished for their treason. Dante’s Inferno (1320) operates a system of contrapasso, or poetic justice – the punishment mirrors or mocks the crime. Collin de Plancy’s Dictionnaire infernal (1818) constructs a hierarchy of demons, categorising all multitude of sins in the process. Occasionally, a figure will descend into the underworld on a mission, whether Jesus (in countless Harrowing of Hell paintings) or Dulle Griet who lays waste to the underworld with her fellow Flemish matriarchs, as depicted by Bruegel the Elder in 1562. Phil Tippett’s Mad God is a descendant of these lineages and yet his feature-length animation, released after a thirty-year gestation, is enigmatic. To find its message, we must accompany it down into the abyss.

Abandon plot all ye who enter may be overstating the formlessness of Mad God. It begins with a broken contract whereby humanity has built a Tower of Babel to challenge the heavens, one borrowed from Bruegel’s spiralling ziggurat design. The world of Mad God appears to be the punishment that followed. It is a disproportionately punitive place without hope or mercy, antithetical to our modern sensibilities, perpetuated by a monstrous God, the Last Man, whose only excuse must be madness or nonexistence. We explore this world via a mysterious First World War-adorned figure called the Assassin, sent by the Last Man to detonate a bomb behind enemy lines with only a deteriorating map to guide him. The nameless inhabitants he encounters are devoid of characterisation or individuality – most strikingly one such group of the suffering are lumbering, spindly humanoids who, with every feature removed, are like living – or dying – Giacometti sculptures. In Tippett’s world, hard-won achievement is instantly undone at terrible cost: monoliths topple over and crush their builders; scavenging creatures are preyed on in turn. Any small victory or tender moment, as when the Assassin encounters one pitiful pleading figure as he is about to go through a trapdoor, is rewarded with torment. It is a world of wanton cruelty and futility.

Mad God challenges us to keep watching. It seethes and squirms, full of corrosion and pestilence, wallowing in filth and degradation. But the first impression of its meticulously rendered stop-motion world is archaeological. We delve down as if hell is one vast landfill site containing ancient fossils, festering viscera and modern junk. Settings are filled with fragments and recognisable traces of our world: telescopes, bicycles, grandfather clocks, music on the radio. Where narrative is outweighed by texture, Tippett’s meticulous eye for detail and world-building is as expansive as it is claustrophobic. Every scene conjures up endless questions, secret histories, a feeling of awe in its terrible as well as wondrous sense. This all reflects the spolia quality of the movie itself, which, in keeping with Tippett’s singular, Oscar-winning style (special effects credits include Stars Wars, 1977; Robocop, 1987; Jurassic Park, 1993), also feels reconstructed from earlier influences. The descent has that cavernous ‘future gothic’ feel of H.R. Giger, especially his work on Alien (1979). Upon landfall, the apocalyptic landscapes of Bosch and Bruegel, teeming with surreal creatures, echo throughout, while the junk that fills each environment bears the (acknowledged) influence of Joseph Cornell whose found-object collages imply unknown histories. Mad God is a film located where Goya’s real-life war atrocities meet his occult apparitions. The question is: what is the purpose of all this?

The answer is not immediately evident. After a while, you start to feel a bleak humour – the despoiling of a Day-Glo Eden for example, or the pointless ingenuity of Heath Robinson-esque contraptions. The fates of the featureless humanoids begin as desperately tragic but through repetition and a kind of semantic satiation, the viewer becomes numb and then callously amused by their fates. Perhaps this is the function of all horror, from Grand Guignol to heavy metal iconography and burgeoning genres like grimdark and cosmic horror – they are not really journeys into the abyss but rather comforting distractions from it.

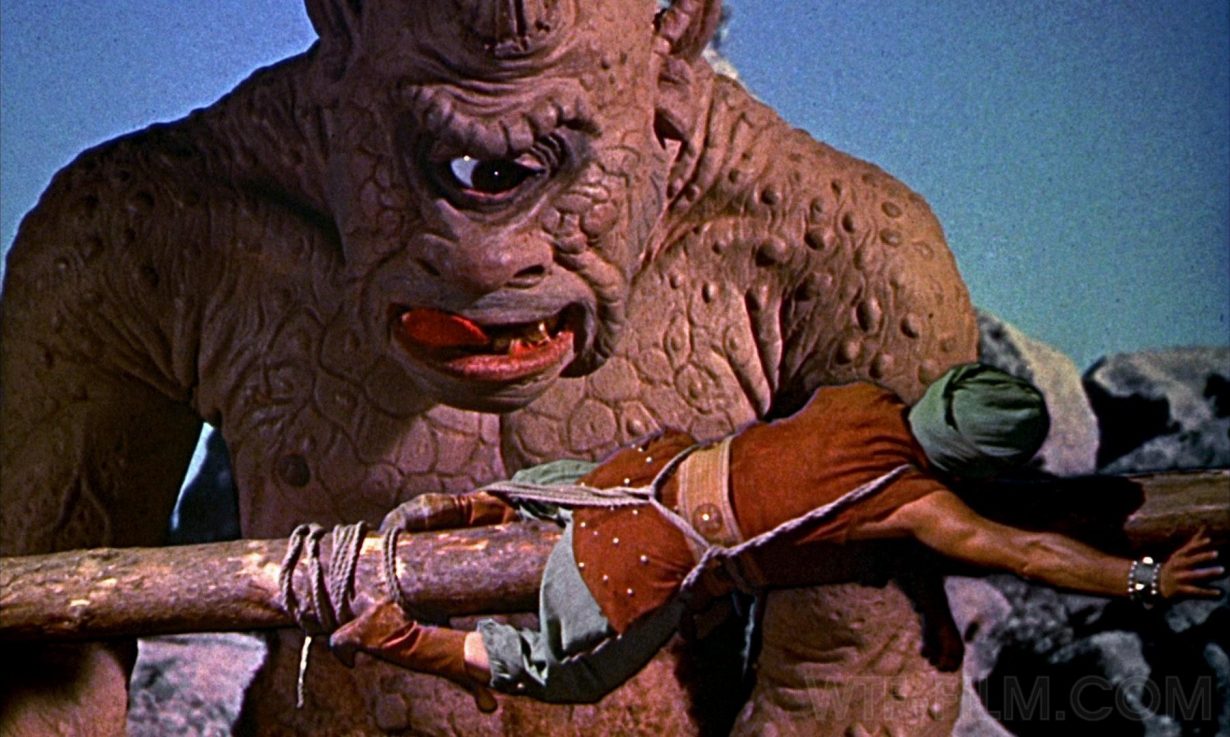

It would be tempting to see Mad God as a jaded commentary on the rise and fall of Tippett’s stop-motion method (or ‘go-motion’, as he likes to describe it), from his childhood amazement at Ray Harryhausen’s cyclops and dragon battle for The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (1958), a film that, by Tippett’s own admission, changed his life, to the ignominy of training the very computer-assisted animators on Jurassic Park, who would replace him. “I think I’m extinct”, Tippett said to Stephen Spielberg after viewing the footage of the effects, a line so resonant that it was paraphrased in the film itself. Mad God doesn’t feel like a journey from optimism to disillusionment though. The film is a resounding testament to what will be lost with the end of stop-motion. This is a world that could not be created in any other medium. CGI rarely reaches the sense of three-dimensional solidity and believability that stop-motion can achieve. Nor can CGI yet reach the strange uncanny valley body-horror depths that almost-human practical effects can achieve (compare John Carpenter’s The Thing in 1982 to its 2011 prequel, for instance). The assumption that CGI would liberate animators in time and labour is questionable; the machine seems only to increase the demands, with Marvel recently receiving complaints about dire special effects and poor working conditions. Tippett may appear to have a jaded view of the universe in Mad God but the real cynics are the studios.

The cumulative effect of watching the film makes you want to somehow cleanse yourself. Perhaps, however fantastical the movie is, this is because we know that every fragment within it is something that has actually happened. And, beyond the physical puppetry, what if our revulsion isn’t because of its gratuitous excess but because Mad God reminds us that dystopian horrors do really exist – and so aren’t that dystopian at all. We do not even need to look back to history’s recent chambers of horrors, to S-21, Jasenovac, Colonia Dignidad, Unit 731 and so on. We know there are secret prisons and black sites operating right now, countless human beings working in toxic mines or living on rubbish dumps, homes transformed into charnel houses by missiles from the sky. There’s no shortage today of destroyed cities, machines despoiling the earth, children living in abject squalor. The nightmarish waste, particularly of human lives, exhibited in Mad Dog is not exclusive to the world of fiction. Perhaps that is why we are tempted to turn away.