Rather than interrogating present-day, citywide issues, the exhibition hovers at surface-level with muddled displays and obscure juxtapositions

‘Tip the world over on its side’, reads a Frank Lloyd Wright quote stencilled on one wall of Hammer Museum’s biennial showcase, ‘and everything loose will wind up in Los Angeles.’ The phrase revives midcentury stereotypes of LA as a sprawling postmodern experiment – an unplanned megalopolis tying disparate communities together with freeways – in contrast to the more concentrated European and Northeastern cities of Wright’s era. Now these aspects of LA are increasingly common across the US: Nashville, Atlanta and Charlotte are the nation’s most sprawling urban regions, and LA doesn’t crack the top five in terms of racial diversity.

But through three floors and many gallery spaces at Hammer’s indoor–outdoor complex, Made in L.A. adopts this earlier vision of the city as its premise. This edition’s curators, Essence Harden and Paulina Pobocha, have eschewed a central theme, instead emphasising a curatorial strategy that, in their words, captures how ‘Los Angeles is many things to many people, and its dissonance is perhaps its most distinguishing feature’. This eclecticism seems to insist on an outdated view at the expense of its selections, ignoring shared interests and experiences in favour of a tired trope. Just as LA used to be, in Aldous Huxley’s words, ‘19 suburbs in search of a metropolis’, Made in L.A. is 28 artists in search of a curator.

Angeles.

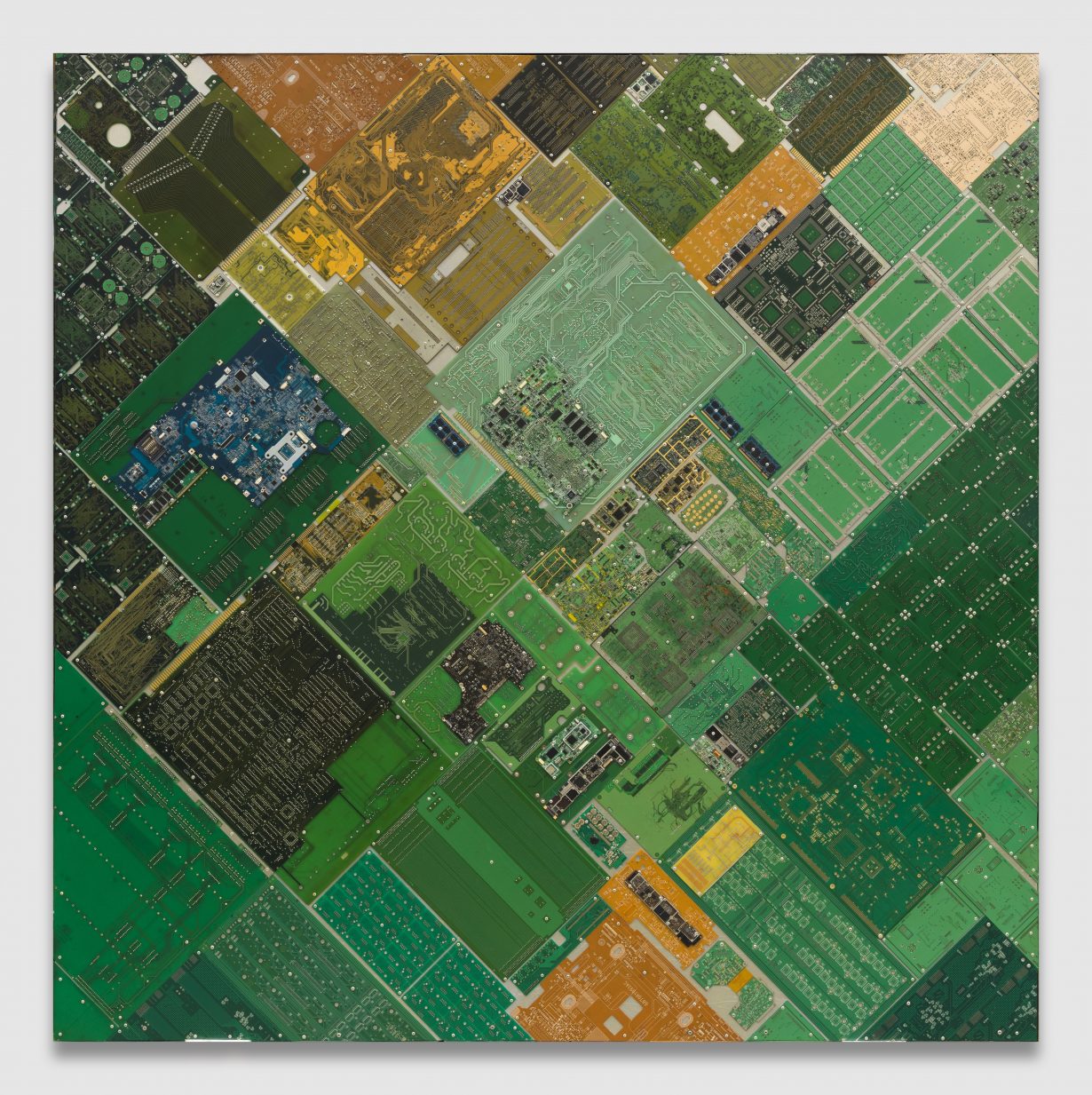

LA art has long thrived on humorous, enlightening juxtapositions – Ed Ruscha’s iconic text-image collages, for example, often combine photographs of majestic Western vistas with banal commercial phrases, culling a new Romantic sublime from LA’s natural beauty and Hollywood-fuelled consumerism – but here curatorial comparisons shade into incoherence. In one room, Alake Shilling’s cartoonish, downtrodden ceramic animals inexplicably abut Carl Cheng’s experiments with midcentury appliances and electronics. From one angle, both artists investigate the ways capitalistic business models shape people and environments, but such comparisons feel strained. Shilling’s Fashion is a Lifestyle Said the Purple Panda in Pucci (2025) features a bemused-looking bear dwarfed by his enormous sneakers and colourful clothing, and Cheng’s 1960s–70s Erosion Series displays piles of sediment worn down by the artist’s retro homemade machines in small wooden boxes, like informational dioramas.

If Ruscha used the city’s cultural contradictions to illuminate deeper truths about LA life, the contrasts present here – in medium, colour and tone – seem to primarily promote an ethos of superficial difference. Amanda Ross-Ho’s Untitled Thresholds (FOUR SEASONS) (2025), a series of four monumental doors each decorated for a scrambled array of holidays – a sequinned pumpkin cutout rests above a green tinsel clover – feels banal alongside Greg Breda’s hauntingly earnest paintings of posed, contemplative Black figures. In the same gallery’s centre are 12 of Brian Rochefort’s biomorphic ceramic vessels, which seem oddly mass-produced in context. Unifying threads between these artworks are difficult to locate, and their juxtapositions obscure, rather than reveal, each artist’s strengths.

framed. Courtesy of the artist

The most thoughtful, relevant explorations on view feel diluted by muddled display, especially in photography and video selections. In a second-floor gallery Peter Tomka presents eerily intimate analogue photographs of everyday still lifes and self-portraits, the result of the artist turning his studio apartment into a homemade camera and darkroom. Across the museum’s terrace, Mike Stoltz’s standout four-channel video installation Pinktoned (Exploded View) (2025) dismantles past and present la street views into component parts, with aged pink slides and contemporary shots appearing on adjacent TV screens. Nicole-Antonia Spagnola’s one-channel video 1-2-3: Apartment Gallery (2025), hidden in a hallway near the restrooms, is a wittily stylised, self aware pastiche of reenacted film tropes. Elsewhere, THEATER (2025), a captivating six-episode narrative series by New Theater Hollywood proprietors Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff, uses documentary footage from NTH’s own stage productions to chart the fictional restoration of an abandoned venue by a fresh Angeleno ‘avant-garde’.

As conventional Hollywood studios struggle and local movie production stutters, many selected artists’ deconstructions of media resonate with shifts in the city at large. Echoing across LA’s film industry and artworld, these present-day, citywide issues are exactly what Made in L.A. could – and should – address in its theme and curating. Instead the exhibition hovers at surface-level, foreclosing deeper, bolder investigations of the city’s experimental and entrepreneurial spirit today, both in the museum and beyond.

Made in L.A. 2025 at Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, through 1 March

From the January & February 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next Ira Sachs on Peter Hujar