Can the self-styled ‘nomadic art biennale’ – with its socially-engaged mission – withstand the weight of its own contradictions?

In November 2018 two tenements in the impoverished, densely populated centre of Marseille collapsed, killing eight people and making around 800 homeless. It was a catastrophe that alerted residents to chronic failures in the way their city was governed: the conservative local authority, it transpired, had been enabling a process of managed decline, allowing the housing in Marseille’s poorer quarters to fall into disrepair while ignoring tenants’ complaints and failing to make crucial repairs. That the majority of the district’s inhabitants came from immigrant backgrounds only added to their sense that they had become the victims of an administratively engineered conspiracy.

This tragedy looms large over the latest edition of Manifesta, which was entering planning stages just as the collapse occurred. The self-styled ‘nomadic art biennale’ has always explored the social context of its host cities, but in this instance there was an added urgency. The latent social issues that suddenly exploded into municipal discourse in the wake of the disaster – institutional racism, homelessness, inequality and gentrification, to name a few – are explored countless times across the 20-plus venues of the exhibition’s sprawling official programme, which takes the visitor on a whirlwind tour through crumbling public museums, project spaces and repurposed industrial structures, and repeatedly attempts to prove that it is more than a glib contemporary art event with a side order of social platitudes: a reasonable description of the previous Manifesta, in Palermo.

The best projects here tackle the political concerns highlighted by the 2018 calamity head-on. Algerian-born architect Samia Henni’s display at the Musée d’Histoire de Marseille, a local history museum improbably located in a 1990s shopping centre, sees her plastering its walls with oral histories from Marseille residents that testify to institutional police racism, as well as maps and statistics explaining the corrosive effects of urban mismanagement. In one damning instance, we learn that the Marseille police force – a body with strong ties to the Pied-Noir community (French colonials born in Algeria who returned to France following Algeria’s independence) – spent decades failing to solve the murders of Algerian nationals; arrests were only made when the killers were caught in the act.

Another gut-punch comes courtesy of the biennale’s single best segment, a show themed around the variable meanings of ‘home’ at the Musée Grobet-Labadié, a former haut-bourgeois townhouse converted into a museum. Martine Derain presents a series of photographs of empty rooms on Marseille’s Rue de la République, a once-bustling street rendered silent when its inhabitants – again, mostly from immigrant backgrounds – were forcibly evicted to make way for an as-yet-unrealised redevelopment project. Footage of protests by a local residents’ association plays out on a TV screen, providing a frenetic contrast to the eerily serene interiors of the vacated spaces.

Elsewhere among the bourgeois furnishings of the Grobet-Labadié, the show turns its eye on America. Cameron Rowland presents part of an ongoing documentary project in which he explores the electronic monitoring of individuals paroled from the US prison system and the profiteering agenda of the contractors tasked with enforcing it. Attached to the wall is an example of the kind of handheld monitoring device used to surveil prisoners on probation, alerting them to curfews and no-go areas: if its instructions are violated, the user faces a return to incarceration. The cost of surveillance is paid for by the prisoners themselves, meaning that the now-widespread law enforcement practice is a lucrative industry. Quite how common this kind of monitoring has become is spelled out in documents displayed alongside: nearly four million people are currently on parole in the US; and some 45 percent of inmates entering prisons in the US have been sent down for electronically detected parole violations.

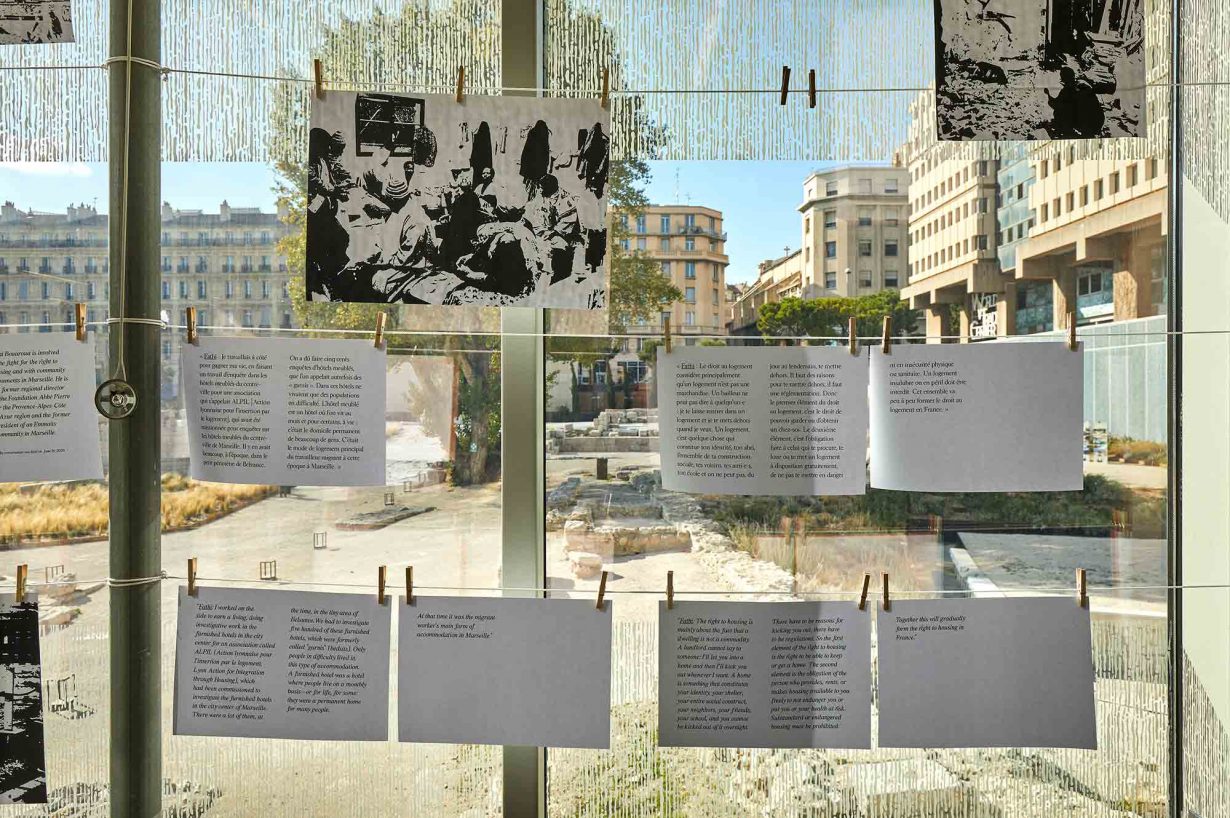

Equally impressive is the biennale’s satellite educational programme, which showcases the archives of various local activist groups. So far the programme has presented an impressively diverse selection of causes, from a pioneering LGBTQ rights collective, to a local hip-hop group that for years campaigned to have a street renamed in honour of a murdered colleague. Filled with vitrines packed with significant documents, film projections and installations, the former cafeteria that serves as a base for the programme is a perfect articulation of the identity Manifesta likes to project: intelligent, inclusive and resolutely contingent.

There are disappointments, too. Some are beyond anyone’s control, not least the cancellation of a planned project at the Musée Cantini by Marc Camille Chaimowicz, who was forced to pull out due to COVID-19 travel concerns. Other failings are less fathomable. Over at the Palais Longchamp – a preposterous Second Empire wedding cake of a building housing the city’s Musée des Beaux-Arts – the prevailing seriousness is offset by Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s daft totemic sculptures, created from recycled taxidermy animals and light-industrial objets trouvés; interspersed with the museum’s Baroque hunting scenes, they strike an odd note. If this was intended as light relief, it doesn’t really work.

Perhaps the most instructive project of all plays out in the courtyard of a slightly down-at-heel musical conservatory, where Mohamed Bourouissa has created a truly disorienting sound installation based on the coded vocal signals Marseille drug dealers use to alert each other to the presence of the police. Watching musical students eating their lunch as the discordant soundtrack plays out immediately puts you in the position of the flâneur, observing at a remove. You wonder what the dealers pursuing their business beyond the conservatory walls make of it all.

This brings us to the complications of this biennale. There is a strangely self-conscious tone to this Manifesta – the official literature constantly reminds you that there is only so much art can do in the face of social upheaval and global pandemic – and small wonder: ever since Marseille won the bid to host it in 2016, there has been a degree of local hostility. Associations of the sort profiled by the educational programme have complained that municipal funds that might otherwise have been available to them were siphoned off to pay for an art event of minimal significance to Marseille residents. Despite the team’s best efforts, this sentiment has never entirely dissipated.

Furthermore, despite Manifesta 13’s focus on the ruinous effects of thoughtless ‘urban regeneration’ schemes, events like this one play their role in enabling the kind of gentrification they condemn. In fairness, the curators – the ICA’s Stefan Kalmár, the V-A-C Foundation’s Katerina Chuchalina and Alya Sebti of Berlin’s Ifa Gallery – will happily discuss this in person. They have done an impressive job given the shit hand they’ve been dealt. Nevertheless, you’re left wondering quite how far an explicitly socially conscious initiative like Manifesta can withstand the weight of its own contradictions when faced with unignorable tragedy. The next edition, in Kosovo, will test this to an even greater extreme.

Manifesta 13, various venues, Marseille, 28 August – 29 October; online visits and events continue until 26 November