Like the launderette, the Internet café is, for me, a last resort when domestic appliances fail. An artwork consisting of fixtures from an Internet café might therefore be expected to evoke bad associations. This wasn’t the case with Johann Arens’s exhibition; if anything, it made me want to visit such places more often.

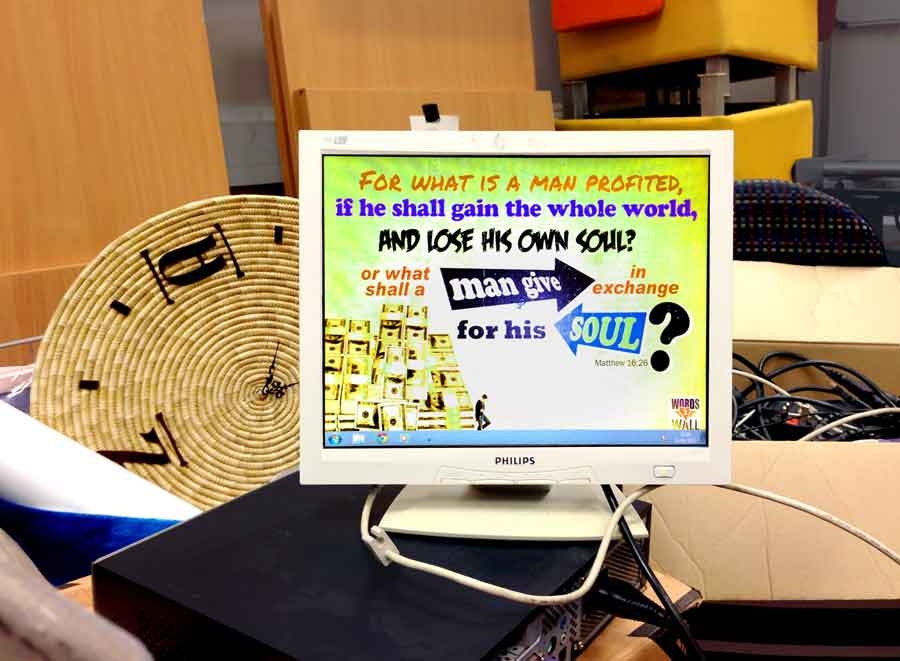

His installation appropriates equipment and furnishings taken from the Internet Centre & Habesha Grocery, an Ethiopian outlet in Tottenham that closed in 2013. In the basement space are six partitioned desks, each with its own PC and swivel chair, some 1990s modular furniture and a wealth of printed matter, ranging from posters offering free legal advice to biblical quotations and a sign requesting patrons to ‘stick your chewing gum here please’. Patrons have duly obliged, creating a neo-dada artefact in the process.

There are also coffee cups, walking sticks, sacks of turmeric used as mouse mats and a number of things that read as emblems of a deracinated community: miniature tom-toms, bags of green coffee beans, ceramic ornaments of animals presumably indigenous to Ethiopia. These recur as leitmotifs, some combined with computer accessories to make sculptures shown in vitrines: a stack of coffee beans with a toy wildebeest and a USB connector; an old PC embedded in a tangle of cables with leather purses and miniature earthenware casseroles.

The desktop computers aren’t online; you can open the browsers, but only to peruse the search histories of Habesha’s past users. Less an exercise in social participation, Arens’s project inclines towards postcolonial ethnography. Alongside the tom-toms and animal ornaments, the Ethiopian alphabet poster and wicker clock, the ‘Western’ elements – the ergonomic wrist-rests and clunky PCs, the dismal modular furniture – seem like trappings of a superannuated cultural hegemony, a collection of ailing Caucasiana. It’s not quite Orientalism in reverse, but there’s a subtle ‘othering’ of the Occident, a discreet chastening of Western technologies and their built-in obsolescence. Look, says the earthenware casserole, peeking out from its nest of cables, I’m still viable.

Is the Internet café still viable? Although, thanks to the smartphone, the idea of going somewhere specifically to access the web now seems anachronistic, such places continue to operate as social hubs. They are also aesthetic bulwarks against the hipsterisation of the high street. To inhabit one is to inhabit the opposite of an Apple advertisement. The hardware is ugly, nothing is cool and once you’ve taken your place in the chicken coop of squalid booths, all you are left with is the bare utility of your own thoughts. The anonymous online profile they confer – relative to the home user – may also be a factor in their appeal.

While it’s true that the grocery side of Habesha’s operation feels underrepresented, Arens’s appropriations constitute a diligent portrait, encompassing the full spectrum of its social character. Sure, the outcome feels embryonic, the research stage of an ongoing project rather than a fully realised work, but there is enough here to make you wonder how the Internet cafés of the future might function, who will use them and what other services, apart from online access, those users will require.

Maybe it’s where the books should go when they close down the public libraries, arranged Dewey Decimally in outlets across the city, Philosophy in Tottenham, Economics in Peckham… My point is only semifacetious. Common to both services is a sense of imminent redundancy. Also, a spirit of auto didacticism pervades Arens’s display, and autodidacticism may be big in the future, if the government’s higher-education policies bear fruit. Whether the Internet café is capable of evolving into a classroom is another matter.

First published in the March 2014 issue.