Björk at MoMA, New York, 8 March – 7 June

Even following recent institutional retrospectives for Kraftwerk and David Bowie, a MoMA survey of Björk’s last two decades may register as pushing it. Yet artist and venue effectively meet in the relativist middle, since neither are what they once were – the institution, like many others, now something of a populist funhouse; the Icelandic musician, her lauded new album aside, lately appearing increasingly interested in multimedia projects like 2011’s record, app and invented-instruments live extravaganza Biophilia. Of course, Björk is a cross-media phenom in general, her videos trumping many artists’ work for ideation, her acting winning prizes at Cannes, etc. Björk additionally promises the increasingly de rigueur upending of the survey format, embedding a semifictional biographical narrative (written with Icelandic writer Sj.n) and building to an ‘immersive music and film experience’ made with LA filmmaker/ artist Andrew Thomas Huang and design team Autodesk.

Les Oracles at XPO, Paris, through 11 April

Curated by Marisa Olson, the German-born, US-based artist/curator/writer who once auditioned for American Idol as an art project, wrote a dissertation live online, is widely credited with giving post-Internet art its name and cofounded the early ‘surfing club’ Nasty Nets, Les Oracles inhabits a different quadrant of the emphatically contemporary. Its ten women artists take science fiction as a vehicle for themes (‘futurism, fantasy, utopia/dystopia, the frontier, embodiment, xenophobia, cosmology & theology, technological change, and evolution’), pulling these together under the sign of the oracle, the frequently female deity that forecasts the future. Smart parallax should be in play – how much of this came true, and in what unexpected ways? – in the work, by artists including Julieta Aranda, Aleksandra Domanovic and Katja Novitskova. And because no show thus far in this column is complete without a fictional component, sci-fi by writer/musician Claire Evans will grace the catalogue.

Simon Ling at Bergen Kunsthall, through 5 April

Simon Ling’s exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall, The Showing Uv It, also sets itself against a sci-fi backdrop: Russell Hoban’s exceptional 1980 novel Riddley Walker, set a couple of thousand years in the future in a postapocalyptic Kent where language has regressed (à la the exhibition title) and a new generation is struggling, in part, to understand objects and what can be intuited of their inner realities. This is surprisingly germane to the English painter’s plein-air urban landscapes and studio-constructed still lifes, which intently track – and rebuild through tilted planes and subtle, pulsing distortion – the haphazard bricolage of London streets and tumbling arrangements of objects. If the looking couldn’t feel closer, hot fringes of fluorescent orange amid the realist paint-handling suggests a transfigured world beneath the outward one, one we can’t quite grasp; as Bergen Kunsthall curator Martin Clark has noted, Ling’s method also has resonances with speculative realism, making him a rare painter broaching that philosophic territory.

Paul Johnson at Focal Point, Southend-on-Sea, through 4 April

At Focal Point, simultaneously, is a mise-en-scène that also feels emphatically after – Paul Johnson’s The Sunless Sea, in which the British artist zooms into futurity in order to consider how we might see the present from then – as a post-utopian scrapyard of sorts, it seems. Processes of time collaborate with the artist’s hand: a dune buggy, made from recycled parts, stands upended and rusted, while ‘sculpture’ as a category also comes to encompass something – seemingly a wallet, though it no longer looks like one – that accreted for five years in one of Johnson’s pockets. Meanwhile, a jerryrigged mythology is suggested by mixing imagery from ancient Yemen with traces of beer crates and plastic bottles. If this sounds like a downer, though, the intent is to blow on embers: to quote the gallery concerning works made from leftover wood in the artist’s studio, ‘The sense of significance bestowed to the objects, which would more commonly be disregarded, offers optimism that these moments of utopia will be regarded in the future and offer a glimmer of hope that such thinking could exist once more.’

Possibilities of the Object: Experiments in Modern and Contemporary Brazilian Art at Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, 13 March – 25 May

The artists in Possibilities of the Object: Experiments in Modern and Contemporary Brazilian Art mostly precede such post-utopian hang-ups. These objects from the last Brazilian half-century or so were intended to be figuratively graspable and actively transformative: often with the aim of reshaping society, as see the work of Cildo Meireles, Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Artur Barrio; sometimes for mystical-formalist reasons, as in the work of, say, Mira Schendel. Since the outset of Neo-Concretism, that aim has often been established by interaction, from Oiticica’s work to the pendant, spice-filled biomorphic structures of Ernesto Neto, such that one legacy of Brazilian art since the 1950s is a decentring of the object – it becomes not something to look at but something to travel through. How far that’ll be reaffirmed or challenged by the curator, Rio art critic Paulo Venancio Filho, remains to be seen. But the show certainly features a scatter of lesser-known names amid the designated hitters, so expect an eff ervescing history lesson at least.

Ydessa Hendeles at ICA, London, 25 March – 17 May

The ICA’s theatre is to become a courtroom (though it might equally be an anatomy class or slave auction, according to advance information), courtesy of Ydessa Hendeles. For From her wooden sleep…, 150 wooden mannequins dating from 1520 to 1930 will gather around a central figure, in a freewheeling argument concerning the past’s pressure on the present, the relativism of artefacts, the power relations between individual and group. Hendeles has form in this regard: formerly a sharp-eyed gallerist in Toronto, she’s also a collector, curator and increasingly something more – her show Partners (The Teddy Bear Project) (2002–3), for example, featured thousands of family photos linked by the presence of the eponymous toy, an archive via the incidental. If that was a curatorial project and, like her others, a well-received one, the self-described ‘object-savant, and an exhibition-maker’ is now, following shows at Andrea Rosen in New York and Johann König in Berlin, being branded as an artist-curator. See for yourself if the first half of the hyphenate feels true.

Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the Work of Six African Women Artists at Wiels, Brussels, through 3 May

More bodies, unsurprisingly, in Body Talk: Feminism, Sexuality and the Body in the Work of Six African Women Artists. Possibly no need to explain what that’s about, then. But it ought to be illuminating, the development of feminist African art since the 1990s perhaps not being hugely familiar to everyone. The best-known figure here, for most, will be the South African Tracey Rose, longstanding maker of superbly confrontational, often performance-oriented videos and photos; others include Marcia Kure, whose watercolours and photographic works hybridise hip-hop style, Victoriana and male and female bodies, and Billie Zangewa’s satire-driven tapestries, revolving around the position of women in urban and social landscapes.

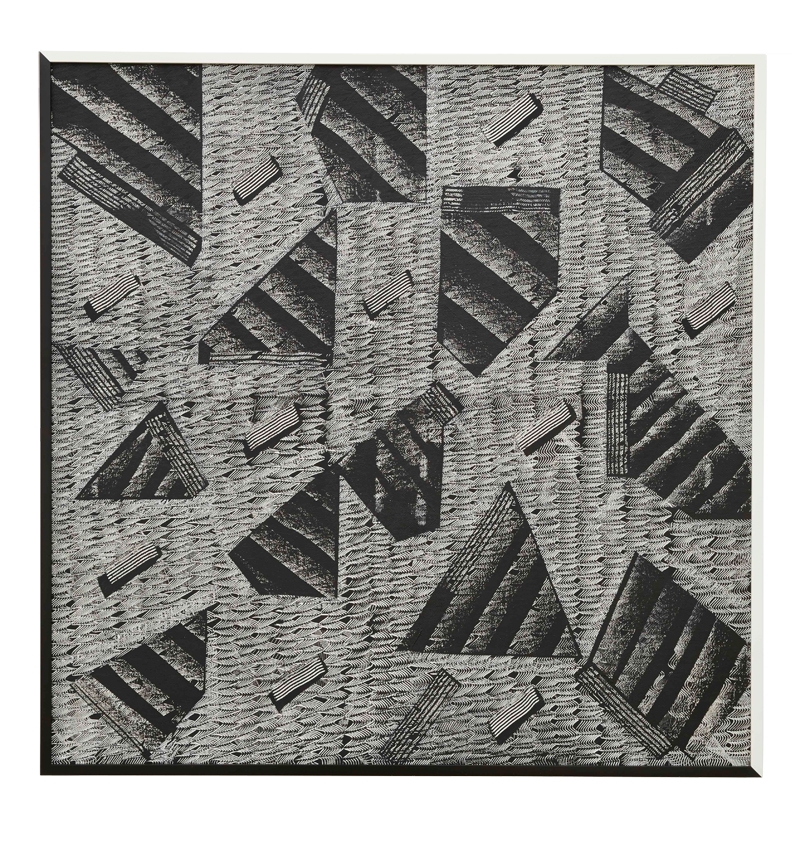

Julia Dault at Marianne Boesky, New York, 20 February – 21 March

Maker’s Mark is a small-batch Kentucky bourbon, lately sold to a Japanese distillery. It’s also the title of Julia Dault’s new show – fittingly, given the name, since her work concerns itself with the conditions of its own making. In the ascendant young Canadian artist’s sculptures, bent or folded and shiny or iridescent materials are tenuously belted together, advertising the forces keeping them in precarious equipoise; in her paintings, often on synthetic supports (pleather, spandex), she paints only to later remove paint, bringing the offbeat ground back. The works take a circular approach to meaning that derives from Postminimalism self-reflexivity, but they also open onto questions of the value of artistic labour. Meanwhile, the pop-giddy, manmade surfaces Dault uses signal further ambivalence, being pleasing to the eye but also inhuman, figuring the maker’s labouring hand as a holdover in a postnature scenario.

Juliette Blightman at Isabella Bortolozzi, Berlin, through 4 April

Juliette Blightman practises discreet intransigence: I’ve seen a show of hers where a cine projector was turned on once a day, briefly, was silent otherwise, and when running showed not much. In a 2008 show, she exhibited an apple plus a goldfish in a bowl and a plant, which her brother came in to feed and water every day at 3pm. The presentation of liminal, unassuming moments is her forte; this, her work asserts, can have a disproportionate recalcitrant force and weight. For her second show at Isabella Bortolozzi, the English artist is expanding into paintings that might, themselves, suggest film stills, as well as a film capturing interim moments in the artist’s life before focusing in on books addressing, pointedly, the notion of selfhood and one’s place in the world. Meanwhile – not clear how yet – the show will also continue in the basement, to a 4/4 rhythm.

Pennacchio Argentato at T293, Naples (offsite project in Naples bank), through 13 April

In the past, artists Pennacchio Argentato have turned the threatening recorded speech – ‘You will never be safe’ – of one of the men who hacked British soldier Lee Rigby to death in Woolwich in 2013 into Perspex lettering and strafed it with fractal imagery, filtering it through technology so that it becomes gaudy, mediated, near-meaningless. They’ve also made body parts out of Kevlar and wavering, ghostly transparent sculptures from the packaging material methacrylate; their work, they’ve said, emphasises ‘the impact of technology and communication, and how these two forces reshape our identity and redefine our assumptions about the nature of ethics and political rights’. What emerges is tactical garbling and amputation of the visual and verbal. For their latest exhibition, expect figures cast from titanium standing in a row and wrinkled, solarised surfaces (of some sort) gracing the walls. This, the artists claim, all points towards a future scenario that asks, specifically, what constitutes the human in a technocratic world based purely on processes of exchange – hence the show being held not in Naples gallery T293, who organised it, but in a Neapolitan bank. Here, evidently, is where the unsafe and the bank safe coexist.

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue.