There’s a fine view of the Danube from a room in the Ludwig Museum, a room covered with pink posters illustrating a hammer and sickle design where the hammer looks suspiciously like a toilet brush. A piece of paper is taped to the window, bearing the clunky legend, ‘My friend dildo says to you take posters, ride on Boris Popovič and take photo and send us please!’ Below, a suction cap adheres a large rubber phallus firmly to the pane. Ride with Self-Photographing (2014) is an installation by the Sarajevo-born Marko Brecelj, who clearly has a bone to pick with Mr Popovič, the current mayor of Koper in Slovenia. In this group show of malcontents and provocateurs, such Frank Zappaesque irreverence is the predominant tone.

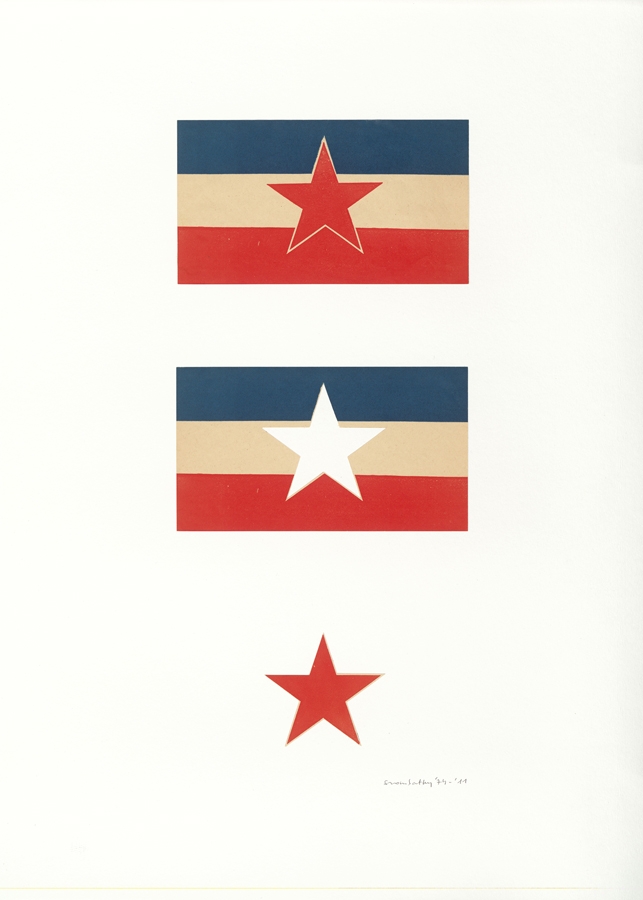

Evoking similar derision are staged photographs by Bálint Szombathy titled Lenin in Budapest (1972–2010), which feature him walking around the city carrying a picture of the old tyrant on a stick. Szombathy also appears in a performance video called Flags I, II (1993–5) where he dances demonically in front of a map of the now-vanished Yugoslavia. More tyrants are destroyed metaphorically in the disrespectful (à la Otto Muehl) canvases of drMáriás, who gives us Stalin in Jackson Pollock’s Studio (2014) and Franco in Joan Miro’s Studio (2014). Deep incongruity follows, then, as we confront 12 heart-clawing drawings by Syrian children from 2014 that feature helicopters, kids on stretchers and planes dropping bombs.

Writing in the London Review of Books (20 November 2014), the historians Nora Berend and Christopher Clark argue that contemporary Hungary, under its prime minister Viktor Orbán, does not register a ‘temporary resurgence of the “far right” in response to economic stress, but a fundamental realignment of political culture, achieved through a combination of populism, intimidation, the distribution of spoils to loyalists and authoritarian tampering with Hungary’s constitutional, electoral and legal structure’. Good timing, then, to hold an exhibition here about the freedom of artists to muse on anarchy and revolution. But exactly how much wriggle room have the locals got right now?

The answer has to be ‘not much’. Most of the works on display, while worthy, are dated and were made in immediate response to the fissures of Mitteleuropa following the fall of the Berlin Wall. There is, to my eye, nothing that challenges the distortions implicit in new monuments here that whitewash Miklós Horthy’s regime in the early-to-mid-twentieth century, which led the country into alliance with the Nazis; nothing that worries about new media controls, little that demands truth and reconciliation. A hint of optimism comes from SI-LA-GI’s work Apology (2008). This framed text piece lists armed conflicts with countries apologising to each other for their aggression – the artist is quoted as proposing this ‘psychologically difficult first step’. Who in power here is listening?

This article was its published in the March 2015 issue.