Richard Hawkins’s art might be summarised as fissures of tightly packed imagery in the midst of devil-may-care gesturalism. This binary interlocks as an emblem of the dynamics of desire. Photographic detail shows the brush what it is questing towards. Abstraction breaks its introversion to reach after a fetish object – a young Matt Dillon, for example – that is interchangeable with a fetishised art object: an Acropolis sculpture of a naked boy.

Exhibiting an early 26-page collage series (Still Ill: An Illuminating Manuscript, 1984) alongside new paintings, Hawkins renders this dynamic retrospective, self-reflexive; ironically, because Still Ill makes the act of drawing a metaphor for onanism. In 2002, he wrote, ‘My daily routine consists of painting in the morning for a few hours and then going back to bed for a long, leisurely stroll through some Brazilian she-male porn. I’m not sure that the former informs the latter, but the latter certainly does inform the former.’

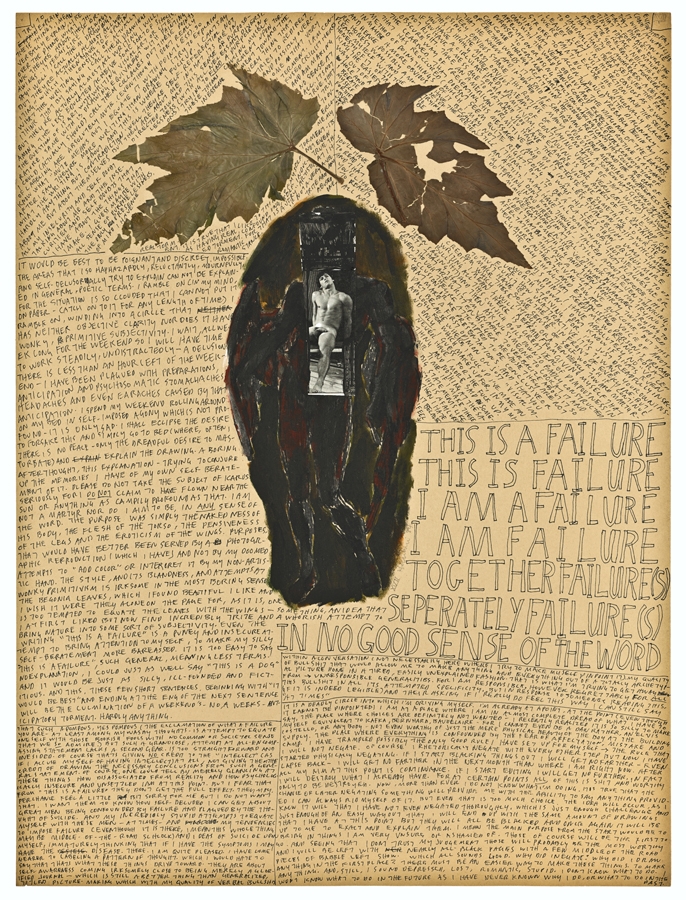

Still Ill diversifies blocks of stream-of-consciousness handwriting with a leaf or a Post- It note, and Polaroids of gay porn. On sheets the size of a broadsheet newspaper, and of a yellowishness that now looks like a sign for age, the writing switches from horizontal to diagonal to spiral formations with a testosterone-fuelled inventiveness. One heading reads, ‘RELENTLESS, INEFFECTUAL, ANGUISH-RIDDEN BULLSHIT WITH NO PURPOSE BUT SELF-AFFLICTION AND NO MEANING OUTSIDE THE PAIN IT CAUSES ITS MAKER’, but quoting seems beside the point: the texts accumulate into a uniform monologuing buzz that corresponds with their visual reduction to a monotone setting for the porn vignettes. Consistently, it is pathetic, beseeching, as self-dramatising as it is self-lacerating, wrestling with the demons of ennui, alienation and sexual frustration.

These were the emotional touchstones of early-1980s postpunk (much of which had gay undercurrents), hence the title of the series, referencing a track from the Smiths’ great self-titled debut album of 1984. It has never occurred to me how onanistic that title was, given Morrissey’s romanticising of the self as a closed but yearning shell of sexual longing. The simultaneity of a cultural reference and a personal testament is typical of Hawkins. His revelations prove to be more objective than they seem. Youthful desperation is recontextualised as a historical phenomenon, a pop-cultural snapshot, its confessional mode as performative. This lets Hawkins off the hook, excuses his callow melodramatics by making them synonymous with the foibles of an era. Allusion and appropriation work both ways: when Hawkins line-draws a pornographic entanglement, he is both placing himself into the proceedings and claiming the protagonists for his world.

But as he points out, 1984 was ‘the first summer of the [AIDS] epidemic and the first deaths of close friends and lovers’, and Still Ill doubles as a memorial to the AIDS dead. ‘FUTILITY’ and ‘FATALITY’ in portentous capitals grey-ghost the print. The models were his ‘cum-triggers’, but the series – or Hawkins’s retrospective framing of it – converts them into archetypes of human vulnerability and transience, isolated by the ebb and flow of his handwriting’s static. They are lost idols, poignantly naked, humiliated by their preposterous poses.

The new paintings – caricaturish depictions of gnarly old queens in bondage gear lording it over skinny teens – form a lugubrious middleaged coda to the studied theatrics of Still Ill. A series of overpainted document folders by William Burroughs, displayed in vitrines, tie into the prevailing theme. Airbrushed streaks of scarlet offset a cutout of a gripped erection. Their inclusion emphasises the literary context of Hawkins’s performance. Nods to Thomas Bernhard (in the press release) and Samuel Beckett (portrayed in a collage) feel like formal references, while the work’s DNA binds it into a gay tradition of cruel desire held at bay by the florid artifice of its literary delivery: de Sade, Genet, Burroughs, Dennis Cooper. The distance between Hawkins’s fifty-thre- and twenty-three-year-old selves is a metaphor for that division between mind and body. As Morrissey, like a dandyish, modern-day Descartes, artfully repined (in the song Still Ill): “Does the body rule the mind or does the mind rule the body? I don’t know.”

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue.