Hanns Eisler (1898–1962) was one of the first artists blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee. The Jewish Austrian composer left Europe for the United States in 1938, escaping the Nazis, and was deported in 1948 for suspected communist activities. Eisler’s FBI file is available on the bureau’s website. Its 686 pages of typewritten notes are almost all redacted, evidence of the fear and suspicion that the celebrated composer, who was nominated for two Oscars for Hollywood film compositions, was a communist informant.

Eisler is the subject of Part File Score (2014), a 12-speaker soundwork in which Susan Philipsz deconstructs three of Eisler’s compositions for film: music for Walter Ruttmann’s Opus III (1924); the piece Eisler is best known for, Fourteen Ways to Describe Rain (1941), which replaced the original soundtrack to Regen (1929), a silent film by Joris Ivens; and a retrospective score for Charlie Chaplin’s The Circus (1928), which Eisler began to develop in 1947, but never finished because he had to leave the US. In Philipsz’s hands, these musical works are trimmed down to a single violin, with each note playing on a different speaker. The speakers are suspended from the ceiling to reach the audience’s eye and ear level. Walking through the space, one cannot stitch together the distinct, individuated sounds into some unified whole. The compound music is intermittent, fractured, and so reflects not only on the life of Philipsz’s subject but also the general atmosphere of anxiety and fear that pervaded the US during the Cold War.

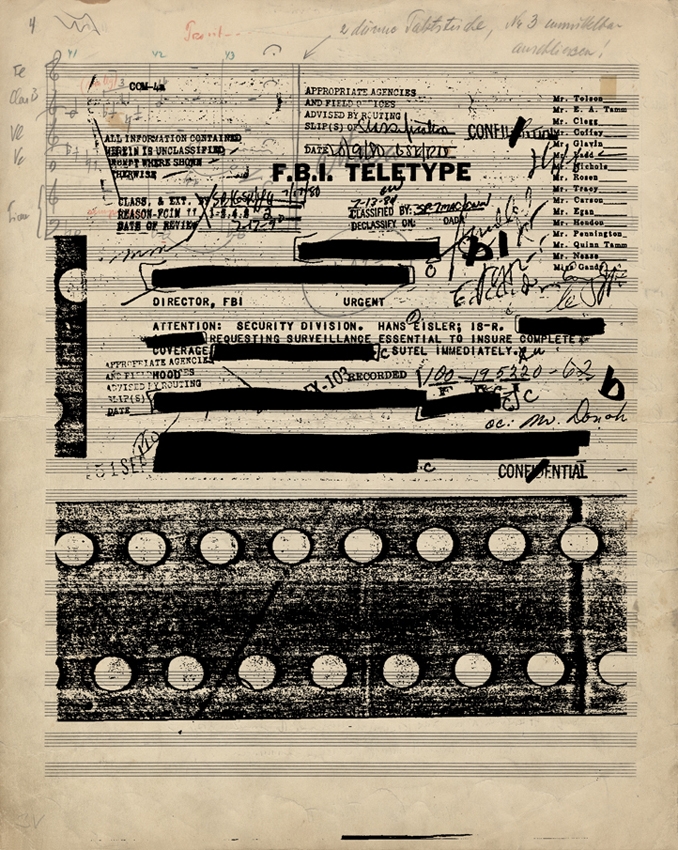

On the gallery walls Philipsz displays 11 digital reproductions of Eisler’s FBI records superimposed over his musical scores. The large framed prints include details from the composer’s life, such as a list of Eisler’s acquaintances, including T.W. Adorno, ‘Bert’ Brecht, Chaplin and Fritz Lang (the name of a person who worked for the Bell Telephone company was erased), as well as letters, internal FBI memos and other ephemera, all printed over Eisler’s scores, which are hand-worked and full of erasures and additions.

The prints are remarkable for the level of detail they reveal about Eisler’s story, but also because they reverberate so strongly today. In light of Edward Snowden’s leak of the US National Security Agency’s illegal wiretapping and the way that these revelations have changed the discourse surrounding governmentsponsored surveillance and the right to privacy, the aesthetic of these prints – the redactions, the stamps reading ‘Confidential’ and ‘FBI Teletype’ – is chillingly contemporary.

As with Study for Strings (2012), Philipsz’s site-specific installation at the Kassel train station for Documenta 13, for which she reworked a composition written in the Theresienstadt concentration camp by the Jewish Czech composer Pavel Haas, here Philipsz shows once again that she is at her best when working with historical material. Her treatment of sound, already a visceral element, which she breaks apart or brings back to a space from which it was drained, offers a substantial emotional experience. It’s never didactic and always contemporary. Hers is not an art of great gestures: it’s the work of slowly chipping away at history, exposing something that is both a mesmerising tribute and a lesson for today.

This article was first published in the March 2015 issue.