Over a decades-long collaboration, the American artists suggest their own creative activism and informal reshaping of the artworld

In Las Vegas Ikebana – the current retrospective of work by sculptors, performance artists and longtime collaborators Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi, at the Columbus Museum of Art at The Pizzuti – there is a work called Talking Book (1988). Hassinger ravelled and braided moss and twigs, part of her long practice of intertwining natural and industrial materials to make her sculptures, to create the shape of an open book holding a Sony Walkman with a cassette tape inserted. Hassinger and Nengudi mailed the tape back and forth between Colorado Springs and New York City, exchanging poetic observations of nature, natural soundscapes, excerpts from performance scripts and intimate narrations. During the sound piece’s little more than 12 minutes, Hassinger repeats, with increasing speed, the statement, “The weeds smell like iron. The wind smells of trees,” and after a brief silent interlude continues evenly repeating, “I want to remember how the fields and the trees look at sunset or dawn.” Their sound collage concludes with Nengudi saying, “Speechless. Wordless. Soundless. We rest. Our message of life sent. The overflow of liquid life running down my leg.” Talking Book encapsulates a connectivity between distinct voices, built over time through a ritual of sharing and vulnerability.

Las Vegas Ikebana is a curatorial compendium of Hassinger and Nengudi’s kinship. Including documentation of performances in video and photography, the walls are covered in decades of artistically and personally intimate correspondences that take the form of letters and art projects. Across nearly five decades of friendship and artistic collaboration, Hassinger and Nengudi’s partnership shaped and was shaped by the political and artistic drive among Black women artists to open the door for themselves and others in an environment that doubted their capacity and relevance. Las Vegas Ikebana documents the duo’s platonic and creative intimacy over decades while also chronicling the duo’s experiences pushing against racism and misogyny. Their partnership is one of discipline and devotion: they raised children together, sustained careers together. As I sat with Las Vegas Ikebana, I was left with a vibratory imprint of their love for one another, but also with troubling questions: how much difference does such a relationship make to the larger mechanics of the artworld? Is such a connection more personally transformative than politically or economically transformative?

Hassinger’s and Nengudi’s individual and collaborative practices came about during a post-Civil Rights Movement cultural explosion in American arts. In 1970 Faith Ringgold and her daughter, art critic Michele Wallace, began the organisation Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation. Black artist consortiums such as Spiral, Where We At, the late Black Arts Movement and the Black exhibition space Just Above Midtown – founded and directed by Linda Goode Bryant – sought not only to make their own infrastructure, but to transform the art community outside of themselves from exclusionary to inclusive. Nengudi first encountered Hassinger’s work in 1976 at the arco Center for Visual Art in Downtown Los Angeles in a two-person show with the painter William Mahan. Nengudi notes in multiple interviews that she was invigorated by encountering another Black woman artist focusing on sculpture and performance at a moment at which Black artists struggled for representation, especially when working in more experimental approaches. Although Hassinger and Nengudi recognised one another within their tight artistic circles in Los Angeles, they finally connected while teaching in a training programme at Brockman Gallery, one of the only Black-owned art enterprises in Los Angeles at the time. Both women had aspired to be dancers, and both of their rejections from dance programmes redirected them into more experimental journeys with art. From there they established a dedication to one another that not only included sticking hand-in-hand through life’s trials – raising children, caring for and losing parents, divorce and career struggles – but also ensuring that they both continued their artistic practices, even if only keeping them on life support. Given that the artists have spent more physical time apart than together, the correspondences in Las Vegas Ikebana extend like a chronological string through cyclical and spiralling ideas and sentiments.

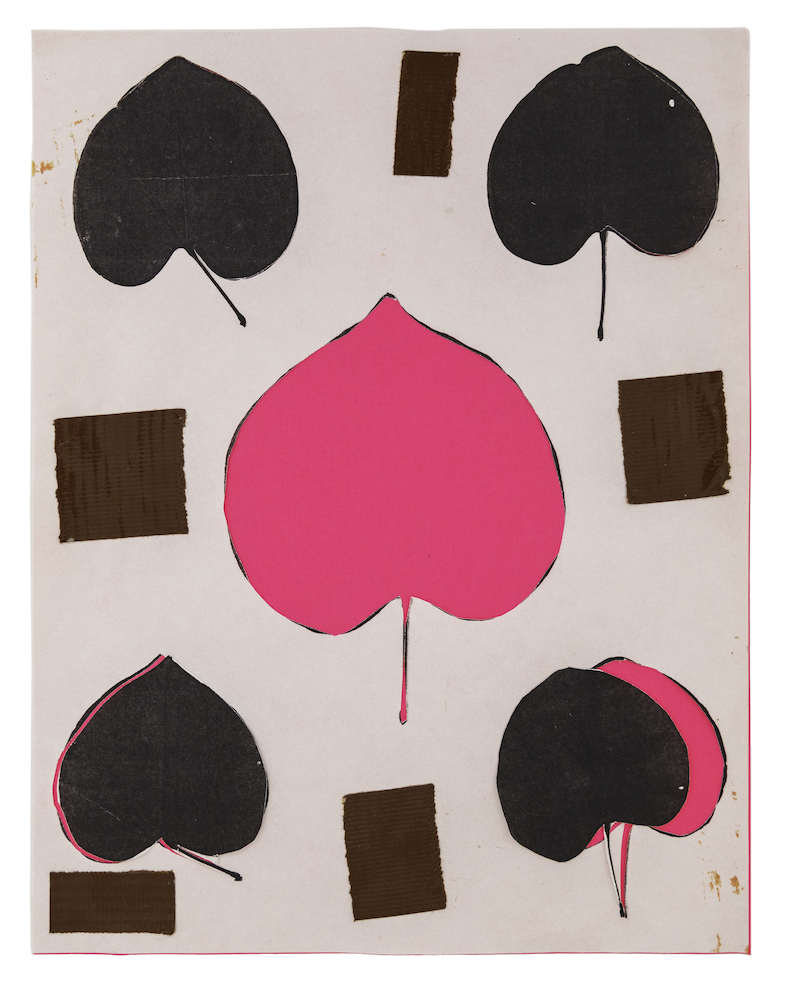

The exhibition takes its name from Hassinger and Nengudi’s 2000 project Las Vegas Ikebana, which includes more than 20 pieces of art mailed between them, inclusive of photos and collages. The first correspondence is a postcard, the front of which includes a centred image of Hassinger surrounded by a collage of magazine cutouts visibly held together and partially covered by masking tape. The note on the back, dated 30 November, reads, ‘Hi Senga, This is the new crap…’ In the space for postage, Nengudi wrote on 4 December, ‘Hi Maren, called you this morning to remind you of l.v.i. Just got this from you in the evening mail. Wow!’ In Hassinger’s contribution Shot Dead, leaf motifs with white circles and crosses are superimposed over playing cards and a text titled ‘The World Record Paper Airp-’. In another piece, titled Ikky Bana, Hassinger centres a hot pink leaf shape on pale pink paper, then surrounds it with subdued bronze squares and black leaf patterns. At one point, Hassinger’s responses explode in technicolour. In The Confetti Fell Like Rain, tattered multicoloured confetti pours in lines from abstracted pencil clouds on golden paper. Nengudi’s contributions are more abstract collage and sparse drawings. A shark with teeth bared floats among green vines and leaves in Untitled (12/9/00). One vine lifts above the leaves, and Nengudi places a purple and pink cosmic starburst at the end of the vine. A postcard from 3 December 2000 reads, ‘Hi Maren, I’m so very tired this evening. I’m going to take the long way out and just put a postcard up – unaltered for my l.v.i. for the day. Glad that we’re doing this. December can be such a pistol. Doing something every-day keeps me steady…’

While ikebana is a specific Japanese practice of arranging flowers, the title of the artwork-in-correspondence came out of a series of references: Hassinger’s mother was adept at flower arrangements, while Hassinger herself spent time working in a flower shop in la’s Pacific Palisades neighbourhood; Nengudi had travelled to Tokyo for a one-year postgraduate programme at Waseda University, where she studied Noh and Kabuki theatre. The ‘Las Vegas’ is more playful and aspirational, signalling the glitter, glitz and fantasy of America’s Playground.

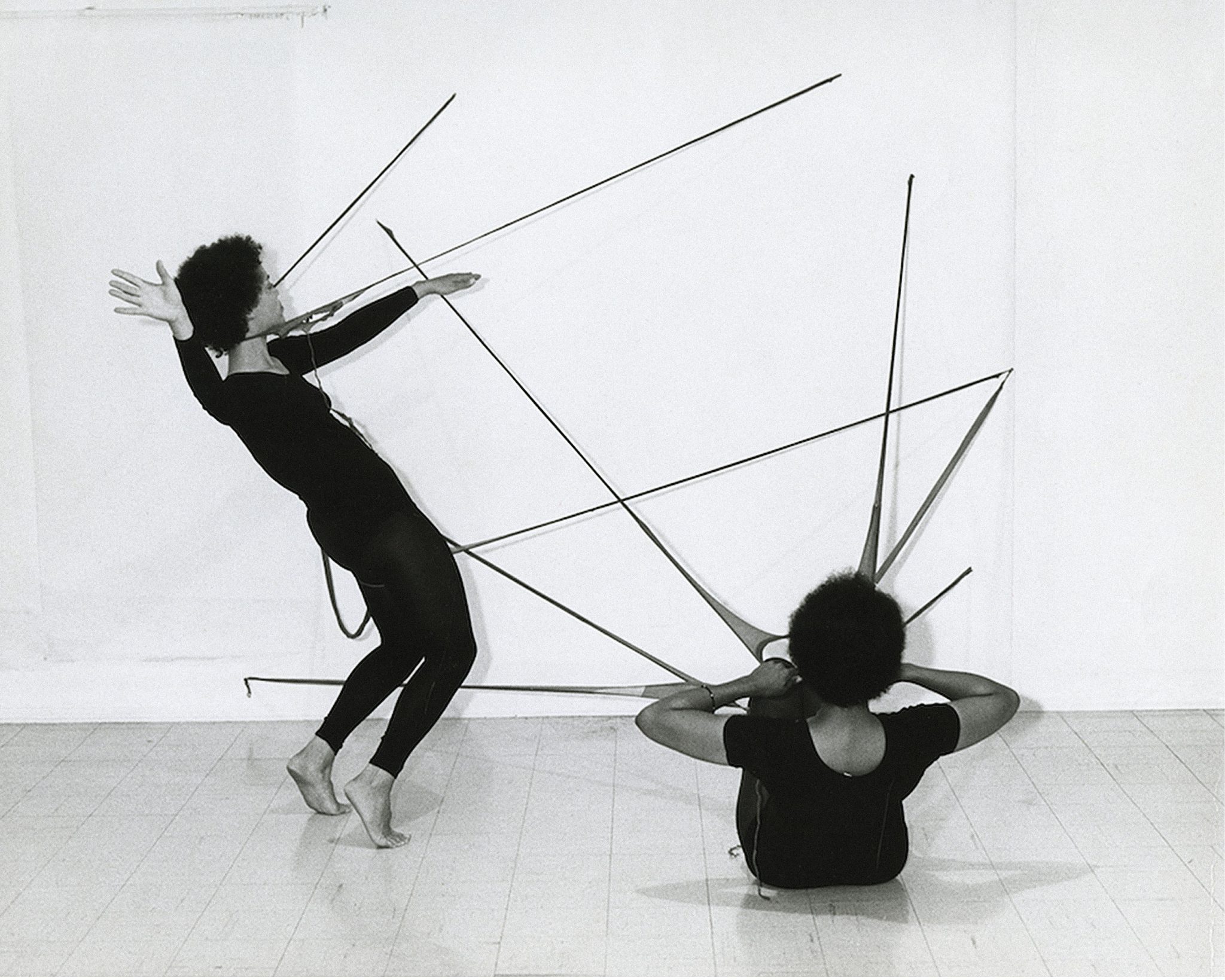

In one of the opening galleries of the exhibition, the legendary dark, nude stockings from Nengudi’s installation and performance r.s.v.p. (1976/2024) are combined with Hassinger’s wire-rope sculptures Leaning (maquette) (1979) and Splintered Starburst (On Dangerous Ground) (1981/2024). The placement emphasises the uniqueness of each artist while highlighting the aesthetics that converse in later galleries. Both Leaning and Splintered Starburst are made from angular bundles of unravelled wire rope – wavy with the remnants of its former wrapped state. The Leaning sculptures in the centre of the gallery appear like meagre fistfuls of wheat frozen in a windswept state. The disk of Splintered Starburst radiates an energy drawn from the wavy pattern in the wire rope, a heavy sense of outward push doubled by its shadow on the white wall. While Hassinger’s work is often grounded in the displacement of nature by human folly, Nengudi’s art is more curious about the body, its softness, its pliability and vulnerability. The stockings of r.s.v.p. are precariously pinned to two points anchored across a corner. The material splits at the crotch of the stockings and is grounded diagonally on the floor by sand-filled nodules. The installation suggests the biological and social stresses of women’s experiences in the world. A phrase that comes to mind from the work is ‘every which way’, a good descriptor for women’s experience throughout history: being pulled every which way. Throughout Las Vegas Ikebana are photos of both Nengudi and Hassinger performing with r.s.v.p. over 40-odd years, using their bodily weight to respond to the tension in the stocking material.

One of Hassinger and Nengudi’s first collaborations was for the piece Ten Minutes (1977), performed in David Hammons’s studio/ dance hall Studio Z. The studio was often used by Hassinger, Nengudi and others to stage performance labs and exhibitions. The opening paragraph of a collective artist statement from 1977 associated with an exhibition titled Studio Z: Individual Collective, held at Long Beach Museum of Art, reads: ‘studio z is a group of artists and associates who joined together through mutual feelings that all forms of the arts are interrelated and should be presented so that painters, writers, musicians, actors, dancers, and crafts-persons will have the opportunity to work together.’ The artist statement reflects the radically inclusive ethos of the time. Similar to other exhibitions in which Hassinger and Nengudi participated, the goal was to invite in people based on shared affinities rather than exclusive demographics. Ten Minutes was conceptualised by Hassinger and involved extemporaneous, lyrical movement between six participants, including Hassinger’s former husband, the writer Peter Hassinger. In photos of the performance at the exhibition, everyone is dressed in white shirts and white pants cinched at the ankle, lithe, extended bodies, exaggerated expressions and gestures, with performers mirroring one another’s movements, emphasised by the performers waving peach tree limbs.

Throughout their career together, Hassinger’s and Nengudi’s practices have been called upon to be in exhibitions that doubled as activist and educational spaces. The piece Talking Book was selected for the 1987 exhibition Coast to Coast: A Women of Color National Artists’ Project, curated by Ringgold and Clarissa Sligh for The Women’s Caucus for Art National Conference in Houston. Ten Minutes emerged from collective acts of making spaces for people to practise togetherness and create networks at David Hammons’s Studio Z. The synergy found in the meeting of art and social justice efforts provided opportunities for Hassinger and Nengudi to push the boundaries of how Black arts were categorised and imagined. The experimental artist Betye Saar, also a Los Angeles native, had set an example for Hassinger and Nengudi to pursue, proving to them that Black arts could be experimental, interdisciplinary and politically effective. The exclusion they faced in their emerging and mid-careers was not only on the part of predominantly white institutions, but also from within the Black community: some artists in the Black Arts Movement often resisted the introduction of artforms that were not figurative or easily monetised. Both Hassinger and Nengudi were part of the 1988 exhibition Art as a Verb in Baltimore, alongside artists like Hammons, Lorraine O’Grady and Howardena Pindell; in an anecdote recounted in an interview in the Las Vegas Ikebana catalogue, Lowery Stokes Sims, art historian and cocurator of Art as a Verb, recalls participating in a panel during the show where afterwards several artists – members of the Black Arts Movement – said to her, “You are destroying Black art! There’s nothing to buy!”

Hassinger and Nengudi have dedicated decades of discipline and tenderness not only to one another, but also to a wider community of Black women artists. Hassinger and Nengudi’s methodologies, despite their aesthetic distinctness, are marked by what many Black women in the arts between the 1970s and today are endeavouring to do through institution building, protest and communal connections: to make more space and invite in more people in an effort to be included in, and eventually transform, exhibition practices, art historical categorisations and the art market. Though by the 1990s some ripple effect of their conviction was evident – with American and Western European gallery spaces showing the work of Renee Cox, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker, Alison Saar and Chakaia Booker, to name a few – we might still ask: how lasting was the impact of the work of these artistic partners? Were there institutional changes that resulted in more readily available opportunities for artists to gainfully but equitably participate in the arts? Even a comparison of Hassinger’s and Nengudi’s individual exhibition histories alludes to these questions. In recent interviews, Hassinger is candid about her lack of institutional inclusion. While Nengudi had opportunities such as exhibiting at the Musée Rath in Geneva in 1971, and was able to continue and sustain an internationally known practice, there was a moment during the 1990s when Hassinger, while lauded, fell out of recognition because of the unevenness in opportunities and resources.

In 1987 Pindell published a report titled ‘Art (World) & Racism: Testimony, Documentation and Statistics’, a compendium of letters between gallerists and museum directors and statistics from art institutions. The findings of Pindell’s report demonstrated that there was indeed a crisis around the inclusion of women and people of colour, especially Black women, in major exhibiting institutions. The 2022 Burns Halperin Report, like Pindell’s, investigated the racial and economic metrics of the artworld in the United States and found that Black American women artists represented only half a percent of acquisitions in 31 of the most visited us museums. While the economic and infrastructural transformations that took place between Pindell’s report and The Burns Halperin Report are great, the actual shifts for Black women artists seem minuscule. Perhaps what Hassinger and Nengudi’s relationship suggests is that such shifts are quieter, building informal institutions that might seed eventually change.

A viewer ends their experience of Las Vegas Ikebana where they begin. In the foyer of The Pizzuti stands an installation bathed in hottish

pink light. A soft, white, gauzy scrim wavers over a blush-coloured

wall intermittently stamped by rosettes made from the rolled-up stockings from previous installations of Nengudi’s r.s.v.p. Some of

the marks are haloed in gold glitter that crackles in the shifting light. To one side, on a low white plinth, a ceramic vase holds a leaning bunch of branches, unbraided wire-rope and a steel cable. Within the entanglement are bunched, stuffed and knotted stockings hanging in the bouquet like resting birds or strange flowers. The installation, also titled Las Vegas Ikebana (2024/2025), contains within it a summary of the gestures that Hassinger and Nengudi have spent a lifetime rehearsing and revising to preserve their togetherness. The coruscating play of Nengudi’s work embraces the heady, open grace of Hassinger’s sculptures to create an installation of joint power. Sentimental, tender and sharp, there is a completeness in this new installation that suffuses the exhibition with excitement and possibility. It embodies the questions: what is possible when we centre community? What is possible when we foolishly depend on love? What is possible when we turn away and starve the systems that become stale without our invention? Retreat from institutions that go broke when they cannot abuse us? How do we coalesce with enough social and emotional maturity to accept that change and resistance will not always be perfect, but that acting in step with one another is always necessary? This retrospective from Hassinger and Nengudi impresses upon the audience that their communal work needs expansion: more partnerships, more communal intent. Las Vegas Ikebana proves that both are transformative. And yet, there is that yawning test between those actions and their ability to replace, if not topple completely, the structures that surround us.

Las Vegas Ikebana: Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi is on

view at Columbus Museum of Art at The Pizzuti through 11 January

From the November 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.