Leckey’s show at Julia Stoschek, his biggest for a decade, considers images as a religious force in a godless age

The title of Mark Leckey’s biggest show for a decade, Enter Thru Medieval Wounds, is a useful shorthand for what it’s tempting to call his metaphysics. In the Middle Ages, the contemplation of religious images – ‘channels of grace’, as the British artist calls them in the exhibition booklet – was considered something like a throughway to the divine. Today, in a relatively godless age, Leckey wants to posit that the collective archive of filmic images – from the earliest cine recordings through the history of videotape and into contemporary computer-generated imagery – might similarly serve as a quasi-magical portal into other times, places, mental states; and that filming and being filmed might have something to do with eternity.

In retrospect, as this labyrinthine, three-floor, 50-plus-work show demonstrates, that’s been the thrust of his art all along, even at its most seemingly worldly. Arriving late in the exhibition is a big-screen presentation, augmented by one of the artist’s bespoke sound-systems, of his 1999 calling card Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore – Leckey’s abstracted, spectral 15-minute video history of UK dance subcultures. Splicing together vintage amateur videotape footage ranging from Northern Soul dancers in brightly lit ballrooms to sky-high blokey acid house dancers, Fiorucci, it’s now clear, was ahead of what came to be called ‘hauntological’ culture in looking back, not without nostalgia but also a sense of creeping unease, at postwar British culture from the millennium. It’s a wayback machine, but Leckey’s footage is so fucked-with – slowed, distorted, with clubbers’ faces sometimes cutout and eerily floating – that it also decisively estranges you from those times. If it’s not the medieval era, the beat that’s still going on is a world away. Yet the film is also an implicit hymn to working-class creativity and entertainment and what’s happened to that under neoliberalism and precarity; and the artist evidently remains interested in how a British underclass might make, or improvise, their fun.

Whether you think that this might, at some point in a successful artist’s career, come to constitute class tourism is up to you. In any case, the show opens with a bevy of recent works, and one of the first we see, after passing through a roomful of sodium lighting that turns skins grey and baptises visitors in a secular, 1980s streetlamp glow, is the video-sculpture To the Old World (Thank You For the Use of Your Body) (2021), screen set into a sculptural bus stop. ‘Fun’, now, for a serfdom of broke bored teens with nowhere to go, might consist – per this video’s core action, variously digitally manipulated – of filming yourself crashing through a bus stop’s window. In another video, Carry Me into The Wilderness (2022), Leckey wanders a London park after the end of pandemic lockdowns, talking ecstatically into the mic about the rapture of being in nature, this alternating with modified imagery of a painting by medieval Sienese painter Lorenzo Monaco depicting a saint in the wilderness, which Leckey has edited to remove said mystic, as if he’s returned to the social world. In dazzleddark (2023), a digital animation based on the amusement park in Margate, a unicorn and a carousel horse marooned on a beach, away from the funfair, have a sort-of-spiritual encounter with a glowing star. You sense the artist aiming, a little effortfully, to reenchant the tawdry contemporary through the prism of the mystical past.

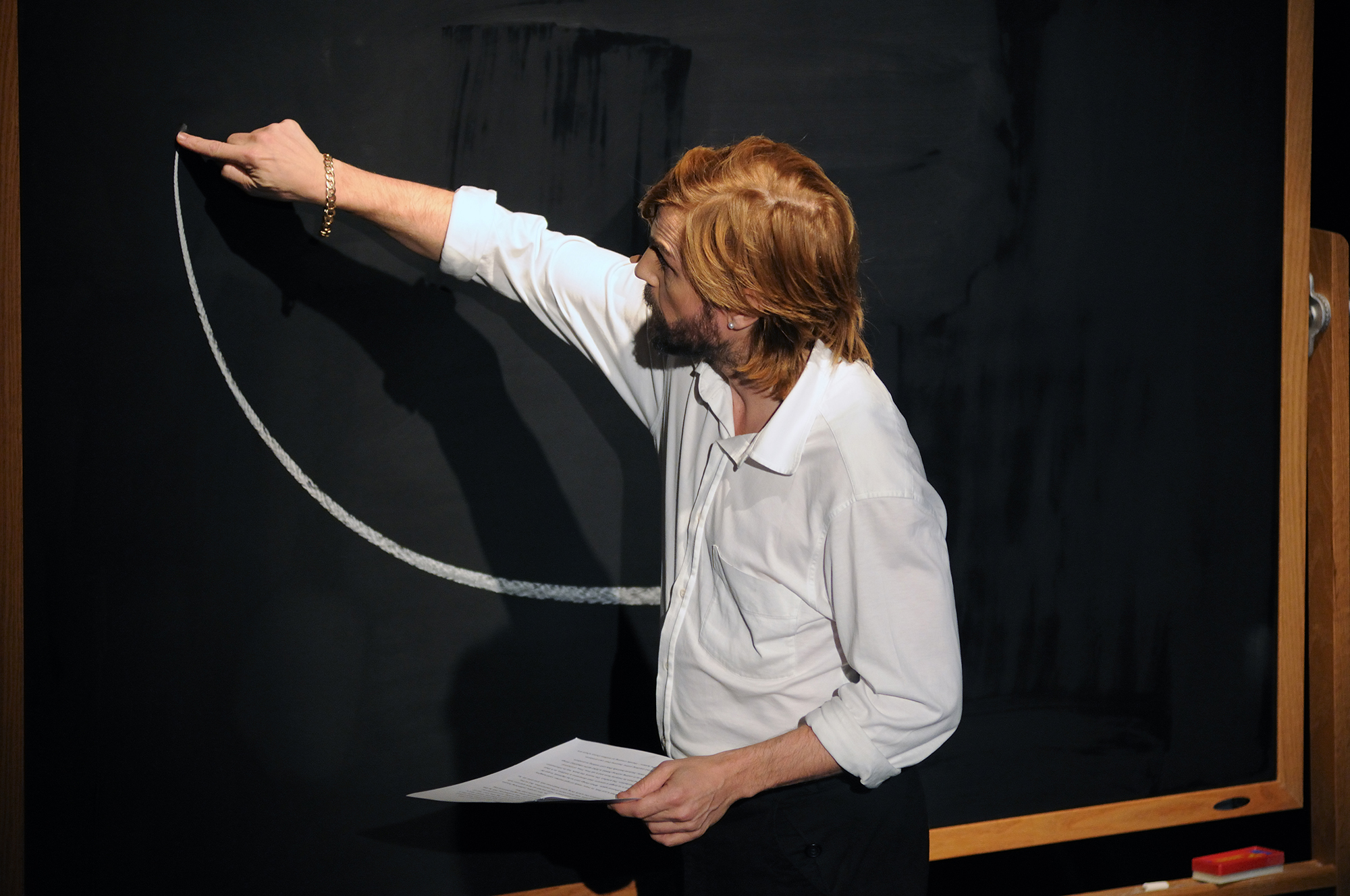

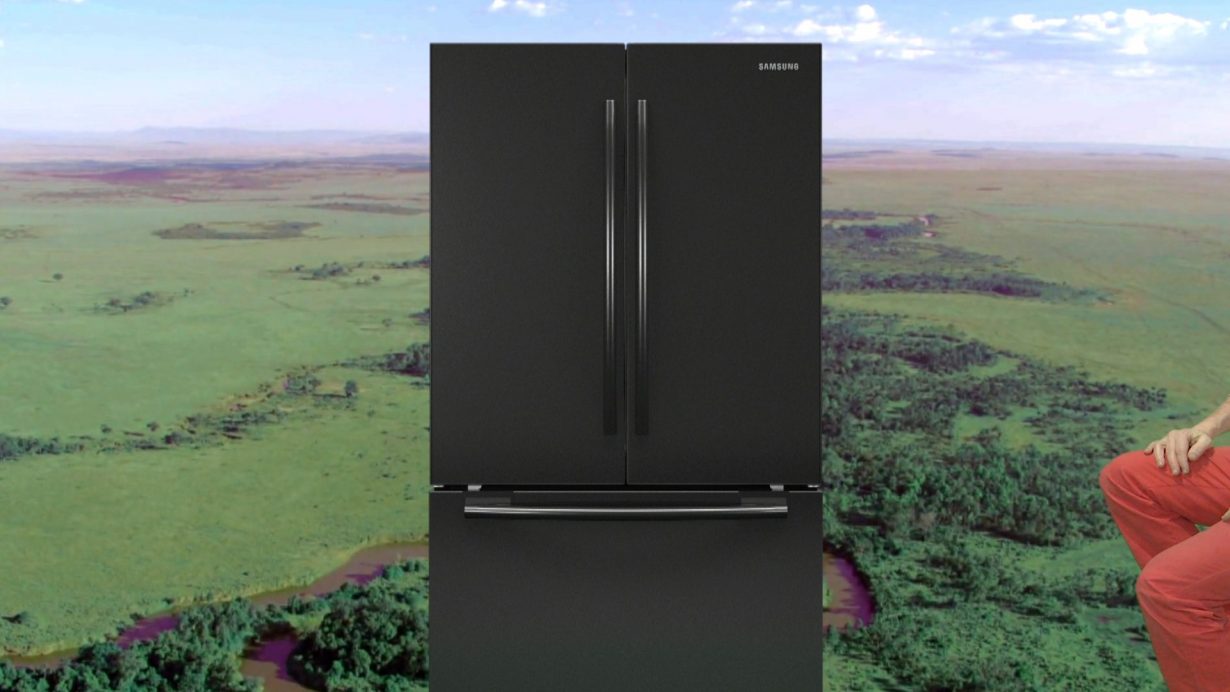

Elsewhere, and relatedly, what comes across repeatedly is Leckey’s advocacy for a kind of technological animism – the act of recording, perhaps, conferring eternal life or at least a burlesque of it. Monitor video Felix Gets Broadcasted (2007) recreates the moment when Felix the Cat became – via a filmed, rotating papier-mâché mannequin of the cartoon feline – the first image broadcast on television. During the contemporaneous filmed lecture-performance Cinema-in-the-Round (2006–08), which moves fleetly between Garfield and Titanic and Philip Guston and much more, Leckey discusses the hyper-solid blackness of cartoons of Felix in terms of a kind of uncanny weight, suggesting that certain 2D images can actually begin to shift into something like three-dimensionality. You can admire the artist’s nuanced semiotic eye here while still feeling that he’s dealing in opinions and mild provocation. But that movement between two and three dimensions is also a leitmotif of his practice, for better or worse. It’s hard to make a living out of video art, and so Leckey has increasingly placed one foot in the sculptural while considering the life of unalive things. That worked well enough in GreenScreenRefrigerator (2010), the artist’s sentient ‘smart’ fridge placed in front of a greenscreen backdrop, which discourses in increasingly haywire, emotive and violent language on how it keeps its contents from going bad. But elsewhere, space-filling elements such as the metal structures into which Leckey increasingly sets his videos, the funfair-ish text-driven light piece VOID (2025) and the polyurethane Inflatable Tetrapod (2025), which mimics the concrete tetrahedrons placed on beaches to combat erosion, so closely mimic the drabness and tackiness of the originals that they’re just depressing to look at.

Film, in all its potential recombinant elasticity, is his wheelhouse. In Dream English Kid, 1964–1999 AD (2015), one of his best latter-day works, Leckey constructs a sidelong, cultural autobiography, a preservation of both film and self, by assembling (mostly found) footage for every year of his life prior to his emergence as an artist: moonshots, vintage film clips, loitering-friendly underpasses, a Joy Division concert bootleg, shots of now-vanished London (eg ‘sexy’ Soho), etc. The queasy, nerve-rattling Shades of Destructors (2005), meanwhile, a kind of allegory of dead-end youth in revolt, departs from a 1954 Graham Greene story about a teenage gang demolishing an old man’s house from within. To make it, Leckey cuts between a grotty 1975 TV adaptation of the story, bits of Donnie Darko (2001) and documentation of Gordon Matta-Clark’s 1973 architecture-cutting project Bronx Floors. As times, places and cultural echelons collapse together, and as the film climaxes with postpunk-ish music by Leckey’s band Jack Too Jack pummelling on the soundtrack, footage shot in Leckey’s studio purports to show the house’s interior, walls progressively and almost occultly graffitied, over and over, destroyed and reborn. Something wounded and dying and coming to new and perhaps eternal life, all at once: film, recorded media, as the crucible. If you didn’t know what Leckey was getting at back then, you likely do now.

Enter Thru Medieval Wounds at Julia Stoschek Foundation, Berlin, through 3 May 2026

From the November 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.

Read next In 2014, Mark Leckey spoke to J.J. Charlesworth about what it means ‘be’ in the midst of a world where images have become things