The artist’s first retrospective in his home country – at MAC VAL, Vitry-sur-Seine – reveals a career spent poking at notions of fame and value

Opening Matthieu Laurette’s first retrospective in his home country is a CRT monitor that plays a looped excerpt of a 1990s French talkshow in which the young artist, straight out of art school, explains, straight-faced, to millions of viewers how to eat for free by taking advantage of the money-back guarantees and other marketing strategies of big brands. Titled Money-Back Products (1993–2001), the project started out as a sort of anarcho-capitalist lifestyle experiment that allowed him to survive as a young artist. It is presented here in the various guises it took over the years: a vitrine display of the eligible products that toured around France as an artwork-cum-information stand; flyers advertising his tour stops and ‘guided tours’ of supermarkets; a very Jeff Koons-ian hyperrealist lifesize wax sculpture of himself pushing a shopping cart filled to the brim with ‘free’ products; and a slew of press clippings from France and abroad, blown up into posters lining the wall below the monitor, with such killer headlines as ‘King of Freebies teaches canny Scots how to bid bills “au revoir”’.

The project is emblematic of Laurette, who for the past 30 years has been operating between the artworld and the real world as a sort of jester figure poking at notions of fame and value (economic, identity, artistic, cultural) in the age of spectacle and unbridled neoliberalism. Laurette’s work could be the love child of conceptualism (and institutional critique), pop art and social sculpture, legacies he acknowledges head-on with remakes of iconic works by Joseph Kosuth, Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys, among the many art-historical references present in the show.

Infiltrating the media and tv in particular became an artistic pursuit for Laurette, sometimes as an actual guest (he famously starred in a very popular dating show, and sent out ‘vernissage’ card invitations for the show’s scheduled broadcast time), or else as a member of the audience, or as ‘wallpaper’, which involved him appearing in the background of on-the-ground news reports waving placards such as ‘Guy Debord is so cool!’ Part artwork, part documentation, the placards and the compiled video excerpts are accompanied here by a projection of the first episode of El Gran Trueque (2000), a TV show he created for Basque television. For this Laurette used a part of the production budget to purchase a car as an initial prize, and invited the public to offer up one of their possessions in exchange, which would become the prize for the following episode. This bartering chain ended grotesquely (and rather quickly) with a set of drinking glasses that was too cheap to trade – an attempt to demonstrate the arbitrary value of money. For Laurette, these ‘infiltrations’ amounted to what he calls ‘irl institutional critique’, reflecting on the power dynamics of society at large by intervening directly in it.

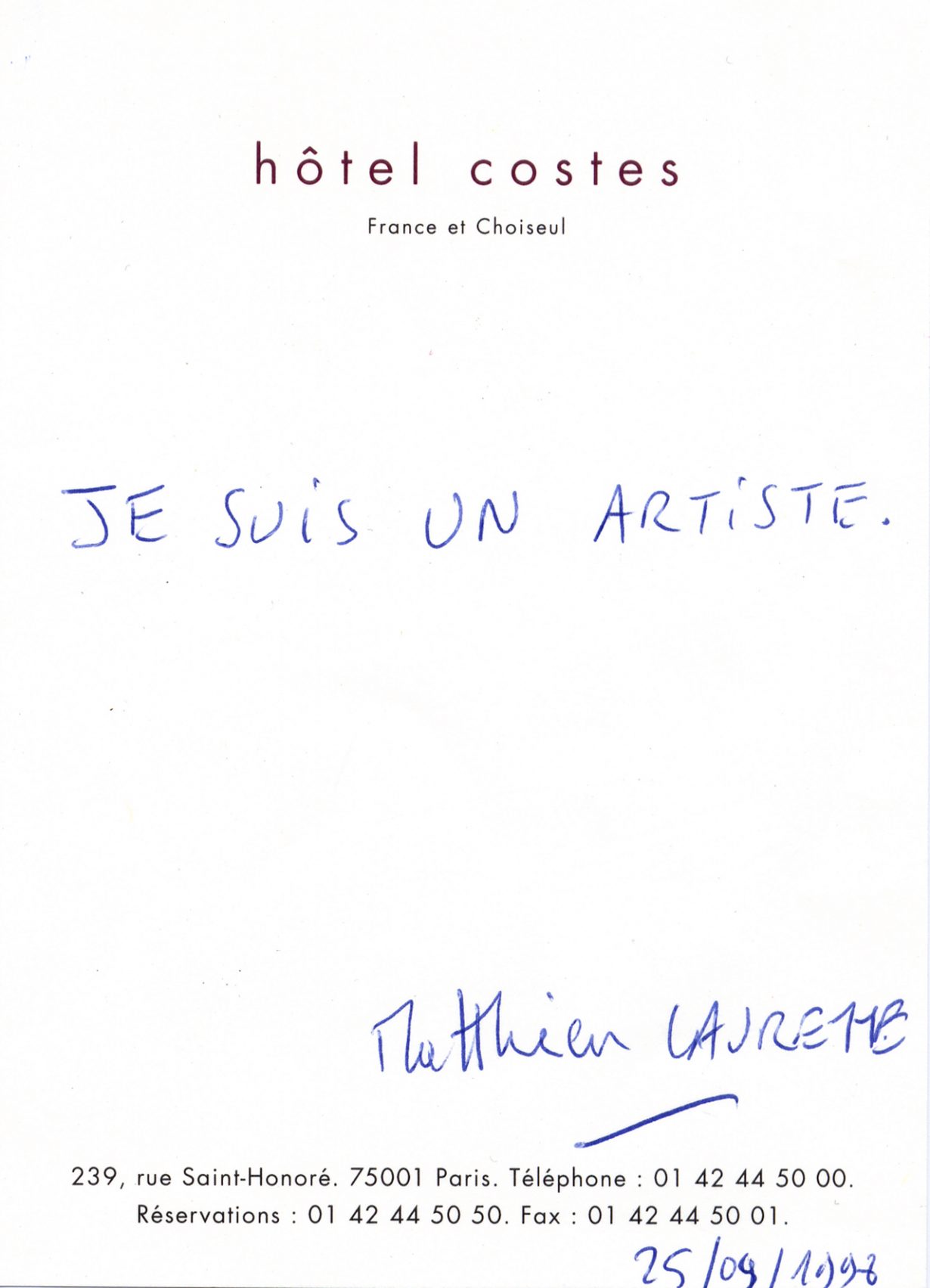

I AM AN ARTIST (Hôtel Costes, Paris, 25 septembre 1998), 1998, pen on hotel stationery, 38 × 29 × 4 cm. © Adagp, Paris 2023. Courtesy the artist

As a good jester, Laurette has turned his own retrospective into a conceptual exercise of sorts, as if observing his career from the outside: Untitled (World Map) (1993–) is a giant map on which the artist has pinned all the locations in which he’s ever exhibited; for Selected Works Currently On Display Elsewhere (1993–), he’s displayed pictures of his works in other concurrent shows on a shelf; meanwhile, largescale views from previous exhibitions hang from the ceiling like billboards advertising his own artistic success. Its title, une rétrospective dérivée, reads as a direct nod to the Situationists’ practice of the dérive, encouraged here by the nonlinear and nonchronological staging of the show, but also to the ‘produit dérivé’, the French term for merchandising. If it is, for Laurette, a way to point to what ends up in the gallery as ‘byproducts’ of the art that happens in the real world, here it also literally translates into a display of actual merch produced for this show in collaboration with a design agency, including flipflops, umbrellas, mousepads and the like, printed with images of his media appearances.

If Laurette lost some of his visibility from the 2000s, it’s perhaps to do with his turn away from the media and towards pure institutional critique, shifting his focus to the very structures that conditioned his existence as an artist. Other Countries Pavilion/Citizenship Project (2001–23), for instance, consists of 112 printed-out letters, presented in a simple grid, sent to the countries not yet represented at the Venice Biennale, candidly offering to act as their representative in exchange for citizenship. Other projects return more directly to economic strategies of survival as an artist: for THINGS (Purchased with funds provided by) (2010–) and DEMANDS & SUPPLIES (2012–), Laurette gets collectors to buy him stuff and cover his expenses in exchange for an A4 contract, turning the actual financial transactions into framed artworks.

These form a crude, necessary commentary on the reality of being an artist in an increasingly financialised market, a reality he’s simultaneously attempting to cheat with delightful irony. Lining another wall is perhaps Laurette’s longest running series, I AM AN ARTIST (1998–), consisting of the titular statement being written on hotel letterheads during his travels, each iteration reading as a sort of mantra or a ritual – to keep his eye on the prize, as it were.

une rétrospective dérivée (1993–2023) at MAC VAL, Vitry-sur-Seine, through 3 March