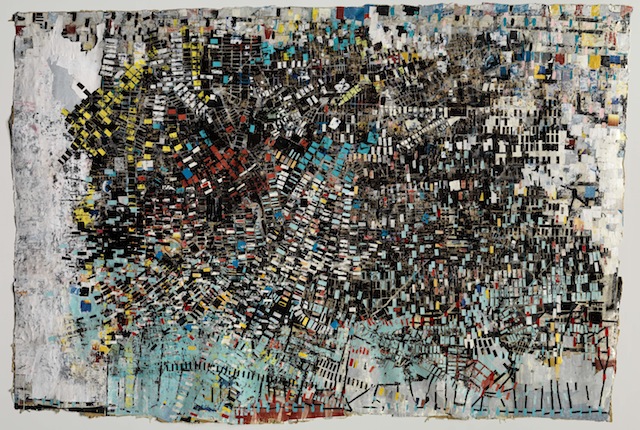

It was a stupid question anyway. Something about having success and opportunity and yet continuing to experiment, still taking risks. Though he has made sculptures, videos and site-specific installations, Mark Bradford was first celebrated, early in his career, for his panoramic, expressively exhausted collage-paintings made from sanded strata of coloured paper, which were almost always understood as reflecting the gritty streetscape of South Central Los Angeles. A long Los Angeles Times profile from 2006, a decade after he graduated from art school, describes him as a ‘hometown boy made good on the international art scene’. His first solo show at a major commercial gallery was in 2001, at Lombard-Freid Fine Arts, New York, sassily titled I Don’t Think You Ready For This Jelly. Since then his work has climbed in value, shored up by solid institutional support – a professional status reflected this year in his representation of the United States at the Venice Biennale.

“All that stuff just sounds like you wanna make me an object,” Bradford tells me. “That’s not gonna happen. You’re not going to make me an object of fame, or make me an object of a hierarchical system. I’ve already been an object. I’ve already been put on the stroll.”

Even back in 2006, that LA Times article cautions its readers of Bradford’s ‘media-hyped professional mythology’. It remains an unavoidable part of any profile on his work, as is reference to his striking physical stature. You can see why he’s tired of being an object. So, with apologies: Bradford grew up in the West Adams neighbourhood of Los Angeles, south of the 10 Freeway, in a once-grand mansion turned into a boarding house for mainly African-American families. He is the only son of a single mother who ran a hair salon where he hung out and occasionally worked. When he was eleven his mother decided to move out of the increasingly troubled neighbourhood to Santa Monica, near the beach, which was almost exclusively white.

“I was way in over my head. I just couldn’t say no. Just hoping that I would not get sick. And the worst feeling was knowing that I couldn’t say no. That I wanted to please them.”

At fifteen, after a dramatic growth spurt, Bradford tells me his body “became a thing. It has always been a thing, it will always be a thing.” Although he was still only a boy, at a svelte 2m-plus, his childhood was behind him. He began going to nightclubs, and dancing, and discovering his sexual identity as a gay man. Bradford turned twenty in 1981, when AIDS was taking hold in the gay community but did not yet have a name. Owing to his striking appearance, he received a lot of attention from other men, which he found himself powerless to refuse. “I was way in over my head. I just couldn’t say no. Just hoping that I would not get sick. And the worst feeling was knowing that I couldn’t say no. That I wanted to please them.”

By the time he was nearly thirty, he says, he realised he was too old for that life – “I didn’t want to be the last guy on the bar stool” – and he decided to apply to CalArts. He hadn’t really made art up until that point and, for a while, he didn’t make much at CalArts either. He dropped out twice, finally graduating in 1995, returning immediately to follow up with an MFA.

“When I decided to go to art school, hell or high water I was going to be a subject,” he tells me. “Some people, God bless them, are born with subjectivity. For some, racially, or for some genders, for some classes, it’s easier. But that wasn’t me. I was born very sensitive, I was kind of pretty, I had low self-esteem. You put all that together, you get in and out of a lot of cars.”

Bradford appears only very occasionally in the art that he has made since the 1990s, and even then in disguise. In 2003 he made Practice, a video of himself awkwardly bouncing a basketball, wearing an LA Lakers jersey and a billowing yellow and purple antebellum skirt. (He was never a basketball player, although strangers always assume he is, especially when he travels first class: just one of the many prejudices from which success does not protect him.)

Bradford’s body is absent, which sets his voice free: he is at once mimicking the delivery of Murphy and all black standup comics

More recently, Bradford recorded a monologue inspired by the notoriously homophobic standup routine captured on Eddie Murphy’s early video Delirious (1983), which Bradford had witnessed live. Spiderman (2015) is an audiowork that unfolds in the gallery accompanied by canned laughter and subtitled text on a black screen. Bradford’s body is absent, which sets his voice free: he is at once mimicking the delivery of Murphy and all black standup comics, delivering an updated (but still unfunny) monologue in a tone also partly inspired by a female friend of the artist’s, who had sat next to him in the audience at the original performance. Bradford remembers hearing Murphy talking about his fear of ‘faggots’ at a time when gays throughout America were dying, seeing people laughing uproariously, and thinking: ‘Uh oh. This is not going to go well.’

From the outset, Bradford’s abstractions compressed representations of both the macro and the micro – a satellite’s view of the urban grid, as in Black Venus (2005), for example, made from the collaged detritus of hair-styling endpapers and posters for small businesses torn from South Central fences – but, increasingly, microscopic cellular patterns and motifs have entered the work. AIDS, Bradford tells me, was too vast and painful a subject for him to deal with until recently, when he showed paintings such as Sample 1, 2 and 3 (all 2015), peppered with malignant-looking spots, based on HIV-infected cells, at an exhibition at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, titled Scorched Earth (2015).

“I’m not good at describing the real. I’m good at pointing to it in an emotional way or an intense way.”

Paradoxically, the extreme closeness of the micro perspective functions as another distancing mechanism, an abstraction that relieves the viewer of the pain of apprehending horrifying subjects at 1:1 scale. For the artist, though, that abstraction is an entry point. “I had to find a way into all this stuff but through a non – quote unquote – real gaze. I’m not good at describing the real. I’m good at pointing to it in an emotional way or an intense way.” The real, in Bradford’s work, is nevertheless fully present; the posters and endpapers are, in a sense, the very fabric of the city, fragments from its economic margins through which other more ephemeral or subjective realities are triangulated. As such, Bradford owes much to the affichiste techniques of Nouveaux Réalistes such as Raymond Hains and Mimmo Rotella. In his ‘Déclaration constitutive du Nouveau Réalisme’ of 1960, the French critic Pierre Restany wrote: ‘If man succeeds in reintegrating himself into the real, he further likens it to his own transcendence, which is emotion, feeling, and, in the end, poetry’.

When, two years ago, Bradford was asked to represent the us in Venice, his first instinct was to decline. He did not know what to do with the invitation. He got grumpy, he says, with people telling him how to be, what it meant, “people turning me into an object. I don’t like that.” Beyond a survey of old and new paintings, video and poetry in the US Pavilion, the project for which his contribution may well be remembered actually takes place outside the walls of the Giardini, in the central Frari district. Bradford has collaborated with the Rio Terà dei Pensieri, a self-supporting collective run from inside two Venetian prisons with the aim of rehabilitating prisoners. With Bradford’s support, the collective has opened a shop selling products made by prisoners, including bags and accessories made from recycled billboard vinyl.

It is easy to see why the bags would appeal to Bradford. He is not, however, appropriating the collective’s wares as artworks, nor exhibiting their activities in an art context as an excerpted sliver of the real. His only authorial intervention is to allow Rio Terà to use one of his images on a limited-edition bag, “to make money”. (He started by listening to the group’s needs; money, he observes, is usually the first thing that people need.)

The six-year project, titled Process Collettivo, follows the Art + Practice foundation that Bradford set up in 2014 with his partner, Allan DiCastro, and the philanthropist Eileen Harris Norton. Based in Leimert Park, a middle-class, predominantly African-American neighbourhood where Bradford’s mother once ran her salon and where he once had his studio, Art + Practice is both a support centre for youth transitioning out of foster care and an exhibition space that has hosted shows by Fred Eversley, Charles Gaines and Alex Da Corte.

Bradford has spent his career reflecting on the vulnerability of the margins and the power of the centre. He began working on his Venice presentation long before Donald Trump’s election in November 2016; he acknowledges his own position of power – within certain sections of the artworld, at least – but admits he never imagined that he would be dragged back to the margins by such an oppressively conservative administration. “But we’re here!” he says, defiantly. “And I know how to be here. I know how to live in a dangerous world that doesn’t want me.” All of us, he says, must remember what it felt like to be the weirdo in the room, before we found our tribe, when the room was violent. “That person”, Bradford says, “is stronger than you think.”

Mark Bradford’s presentation for the us Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, titled Tomorrow Is Another Day, is on view from 13 May to 26 November. The Rio Terà dei Pensieri kiosk is located in Campo S. Stefano, Venice. Bradford’s work is also included in Darkness Made Visible: Derek Jarman and Mark Bradford, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through 30 July, and Shade: Clyfford Still/Mark Bradford at the Denver Art Museum and Clyfford Still Museum, both in Denver, through 16 July

From the May 2017 issue of ArtReview