57th Venice Biennale, various venues, 13 May – 26 November

Let’s say you’ve agreed to direct the 57th Venice Biennale, and your stint coincides with a pivot point in modern history. Do you go all-out topical, making the 122-year-old event an exhibition-as-newspaper? Then you’re not Christine Macel. Viva Arte Viva, the title the Centre Pompidou’s chief curator has chosen, positions art as a humanist category, outlasting the moment; ‘the last bastion’, she’s said, against individualism and indifference. Accordingly, her international exhibition is not a showy barometer of the new. Though 103 of its 120 artists have apparently never before exhibited in the Biennale, the show is – she told a blogger recently – ‘the fruit of my research since 1995’. Partly a rebuke to short memories, it will offer a ‘connected wandering’, in nine professed chapters (including a ‘Pavilion of Artists and Books’ and a ‘Pavilion of Time and Infinity’), involving artists ranging from the missing-and-presumed-dead Bas Jan Ader to the Chinese conceptualist Tao Zhou; from the octogenarian Giorgio Griffa to the barely-thirty Rachel Rose; from the excellently named, transgenerational, relatively sub rosa Mondrian Fan Club – David Medalla and Adam Nankervis – to the ubiquitous Olafur Eliasson. (That artists and not themes are the heartbeat of Macel’s show was reaffirmed by the announcement of Open Table, a weekly lunch-with-an-exhibiting-artist programme.) The national pavilions, of course, will be as directly topical as they like: with Bosnia and Herzegovina’s group show University of Disaster, Ireland’s Jesse Jones solo Tremble Tremble, Latvia’s What Can Go Wrong and the sinking Polynesian island of Tuvalu’s Climate Canary, you won’t forget it’s 2017.

Geta Bratescu, Camden Arts Centre, London, through 18 June

The Romanian Pavilion will be dedicated to Geta Bratescu, ninety-year-old former linchpin of the East European avant-garde, who previously showed in Venice four years ago and before that 53 years earlier. Hot property these days, she also has a solo exhibition at London’s Camden Arts Centre. While working under Ceausescu’s regime, Bratescu focused on the studio as a space for self-preservation and the protection of identity: see her filmed performance Atelierul (The Studio, 1978), in which she defines the studio with gestures even as it circumscribes her movements. Within her atelier’s confines, and while focusing on redefining ‘the line’, she exhibited a pointedly expansive range. She moved, specifically, from classicist drawings of hands to textile works – a self-defined style of ‘drawing with a sewing machine’ in which she sometimes used materials bequeathed by her mother, and explored the Greek myth of Medea, the mother who killed her children after her husband betrayed her – to, later, collage works, or ‘drawing with scissors’. In her London show, the approach taken concerning Bratescu’s work is discernible in the title – The Studio, A Tireless, Ongoing Space.

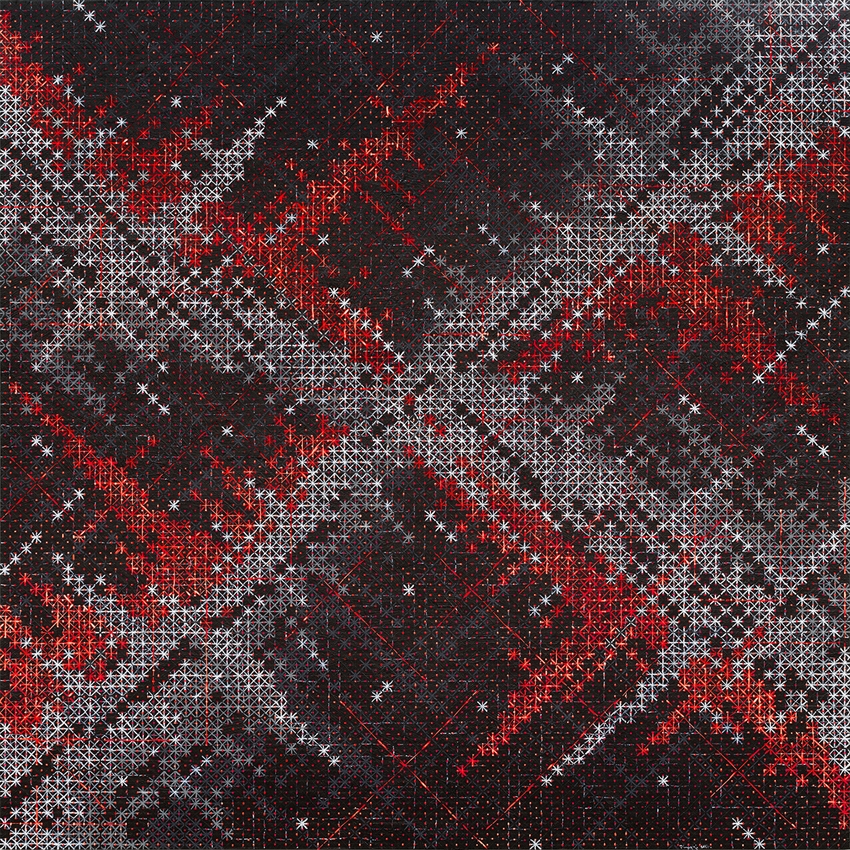

Ding Yi, Timothy Taylor, London, 19 May – 24 June

Across London, China. Since the mid-1980s Ding Yi has restricted himself too, limiting his painterly vocabulary to miniature X’s and +’s, for various reasons: he worked early on for a printing company, and the cross is a printer’s mark used to divide a surface; he didn’t want visible influence from either classical Chinese art or Western Modernism; and, to judge from his changeable canvases, he sought to show just how much can be done with such unpromising ingredients. Over the decades Ding’s paintings have shifted from winking grids recalling Mondrian’s Broadway Boogie-Woogie (1942–3; he self-confessedly didn’t get Modernism out of his system after all) to something like psychedelic tartan; from hot interlocking patterns recalling the bright artificial light of his home city, Shanghai, to – lately – ominous, dark abstractions that look like aerial drone-views of cities at night, data streams or unknowable diagrams, all composed of tiny iterations of his signature blank glyphs. One of China’s most marketable painters, Ding is thus also perhaps one of its most philosophical. Whatever aesthetic arises – whether the modernising face of China’s cities, or views for computers rather than people – crosses, rearranged, can translate and convey it. Here, he has his first solo show in the UK’s capital, focusing on recent work.

Maria Farrar, Mother’s Tankstation, Dublin, 24 May – 1 July

A comparable synthesis of East/West influences animates the paintings of Maria Farrar, who was born in the Philippines, educated in Japan, art-schooled in the .. and is now based in London. Her markmaking, as the Mother’s Tankstation exhibition straits demonstrates, sits midway between Japanese calligraphy and the expressive brushwork of modernist painting post-Manet – the stroke not just as tool for depiction but autonomous thing-in-itself. From what we hear, Farrar paints Zen calligrapher-style, pausing lengthily over a mark and deciding what it might portend before diving in and adding to it. The results, pointedly out of time and place, nevertheless slant autobiographical; as see, for example, Saving my mum and dad from drowning in the Shimonoseki Straits (2017), which zooms in on wavy, inky-blue Japanese waters, lifebelts and limbs, and feels at once tumultuous and humorous, improvised and right.

Rachel Whiteread, Galleria Lorcan O’Neill, Rome, 26 May – 29 July

We can safely assume Rachel Whiteread hasn’t seen Farrar’s work, as in a recent newspaper interview the British artist said she doesn’t look at new art (but even so, she’s certain it’s all rubbish). Always more inclined to Mitteleuropean gravitas than her YBA peers, Whiteread diverts the saved time into her work, and if the latter has long dealt with traces of history on all scales, that makes Rome a logical, if not too logical, site. Whiteread has been casting doors there, alchemising them into bluish clear-resin pseudopaintings propped fragilely against the wall. While doors turn transparent, windows are effectively smoked, figuring – in examples we’ve seen – as solid blocks of deep blue or rust-brown resin. Elsewhere she branches out into ‘sculptural drawings’, involving papier-mâché and gold leaf, and looking like unfolded packaging coaxed into abstract compositions somewhere between Richard Tuttle and James Lee Byars; jokes about ‘casting aside’ aren’t applicable.

Bruno Gironcoli, Clearing, Brussels, through 15 July

‘Sculpture based on everyday objects’ is a category commodious enough that both Whiteread and Bruno Gironcoli can inhabit it. That’s despite the former’s artworks looking, well, how they do, and those of the Austrian modernist – who first trained as a fine metalworker, emerged as an artist in the mid-1960s and died in 2010 – being complex agglomerations of familiar things, scaled up and fused in defamiliarising ways, unified by monochromatic coatings of metallic paint. If his art first looked futuristic and later retro-futuristic, when contextualised in a forward-thinking gallery like New York/Brussels space Clearing, it appears outside of time, its idiosyncratic strangeness a testament to explicatory contexts falling away. (Admittedly the artist always fell voluntarily between the cracks, his practice owing something to surrealist-era Giacometti and something else to Pop.) Either way, Gironcoli now looks new and confounding again, and surely he’d approve of that.

Simone Fattal, Galerie Balice Hertling, Paris, through 17 June

A similar chic gallery/older artist approach is underway at Balice Hertling, which has been rewardingly exhibiting Simone Fattal awhile. The Damascus-born artist, who has lived in France, Lebanon –.leaving in 1980, five years after civil war broke out – and California, and now resides again in Paris, has worked extensively in the very hands-on materials of clay and collage. Her ceramics – heavy-legged and small-headed standing figures, interacting or lonesome; buildings, barred windows, animals – withhold the worldly specificity that bursts out in her collages, fashioned from newspapers and magazines, and punchily assembling bits of antiquity, hot splashes of colour, Arabic scripts and images of Fattal herself in a kind of ongoing autobiography, testament to being here, to dailiness. Before she left Lebanon, though, she made paintings, and it’s these that the current show focuses on. Their date-range stretching through the 1970s, they’re variously glowing and wispy landscapes, sometimes sliding into full abstraction but often halfway between a thing and a feeling about it. A year before war begins, Fattal’s imagery becomes bleached out, and by Le Mont Sannine (1979) there’s almost nothing left: just pale pinkish streaks suggesting mountains in a mottled field of o£-white.

Heather Rasmussen, Acme, Los Angeles, 13 May – 10 June

The body is a repeated focus in Heather Rasmussen’s work, and unsurprisingly so, since the artist, who operates mostly in photography, video and sculpture, is also apparently a dancer. Her Untitled series of photographs (2013–), sitting somewhere between refracted sculpture and still life, and concerned with movement and deterioration, includes casts of her own lightly bloodied feet and uses fruits and vegetables as limbic stand-ins. Such preoccupations continue in her new work, which has the appealing crispness and poise of editorial photography but is contrarily full of jammed signals. Expect cleanly unhinged choreographies of bare limbs concealed and multiplied by sheets of mirror, plus the odd phallic gourd. In these works, though, the Santa Ana-born artist is also making ‘recitations’ of ‘surreal and visceral’ images by René Magritte, German-American artist Hans Breder and Hungarian artist/ performer/musician Ujj Zsuzsi. She’s figuratively inhabiting other artists’ bodies (and minds) for a while, and, perhaps, continuing her latent project of articulating that most fundamental, existential commonality – what it means to live in a body – without being obvious about it.

Win McCarthy, Silberkuppe, Berlin, through 24 June

Win McCarthy could easily write his own text concerning his show at Silberkuppe, and maybe will. A 2013 exhibition in Düsseldorf, featuring some homespun, loosely Robert Gober-ish sculptures, came complete with a press-release poem. Two years later, for his debut show in New York, the thirty-one-year-old Brooklyn-born artist supplied a contextual screed about trying to draw his own face, an accompaniment to a seductive yet elusive show revolving around latex casts (with handwritten angst-laden annotations, eg the one-worder ‘nausea’, and, yes, partial self-portraits) and wood, glass and steel constructions. For his third solo exhibition we’re primed to expect a series of ‘new glass mask sculptures’, and looking forward, since on past form McCarthy can take a relatively stock subject – the unscratchable itch of self-knowledge – and, via his grasp of unbuttoned aesthetics, make inquiring inwardness reverberate with intrigue.

Shara Hughes, Rachel Uffner Gallery, New York, through 25 June

Third in this unofficial trilogy of ‘American artists sticking to one theme and getting something new out of it’, meanwhile, is Shara Hughes, a kaleidoscopic figurative painter in her mid-thirties. Part of a recent lineage that includes Katherine Bernhardt and Dana Schutz, in her exuberant, loosely handled interiors and landscapes – sometimes peopled, sometimes not – Hughes allies colours with Matissean heat to truncated narratives and overflowing detail work. Lately, she says, she’s ‘been thinking about the many ways in which one can view the same object, and how far one idea or one shape can be stretched, simply through how it is presented’; her new show accordingly runs variations on a fixed subject via a set of ‘inverted landscape’ paintings (plus some 15 drawings), in irradiated hues, where space seems to twist itself inside out. There’s some Paul Gauguin channelled here, but the closest cousin might be David Hockney’s latter-day landscapes in the Los Angeles canyons, and you can imagine that Hughes doesn’t care whether that’s cool or not, so assertively if sociably hermetic do her works appear. One title nails the prevailing mood: Comfortably Edgy.

From the May 2017 issue of ArtReview