There’s no discernible theme to this exuberant multigenerational survey at London’s Hayward Gallery – just an exhibition boldly living up to its title

Painting is having its temperature taken again, and evidently the patient is in rude health. Cramming 135 works into London’s Hayward Gallery, Mixing It Up: Painting Today is an exuberant multigenerational survey bringing together 31 painters ostensibly connected by nothing other than a commonality of medium and that they all work in the UK. Curator Ralph Rugoff explains his rationale in the catalogue, writing that the artists ‘share a significant interest in mining their medium’s exceptional multiplicity, and exploiting its potential as a format in which things can be mixed up as in no other’. Put another way, there is no discernible theme here, just an exhibition boldly living up to its title. The result is a joyfully disjointed testament to painting’s unswerving vitality.

Walking around the galleries, one is struck at just how materially conventional the selection is. It’s been more than 70 years since postwar artists began probing painting’s boundaries by expanding it spatially and materially, yet most works here are resolutely bound to the medium’s historical, market-friendly parameters. Nonetheless, some outliers are found amidst the preponderance of stretched canvases, such as the hip-hop-inspired works of Alvaro Barrington; his Ikea-inflected brutalism ditches cotton duck for carpet and wooden stretchers for unwieldy concrete cubes. Another is Samara Scott, whose inclusion is perplexing since she describes her concoctions of toilet cleaner, shampoo and cooking oil on the wall text as ‘almost a total resistance to painting’. In a show where painting’s heterogeneity is repeatedly demonstrated from within conventional confines, her works feel like interlopers.

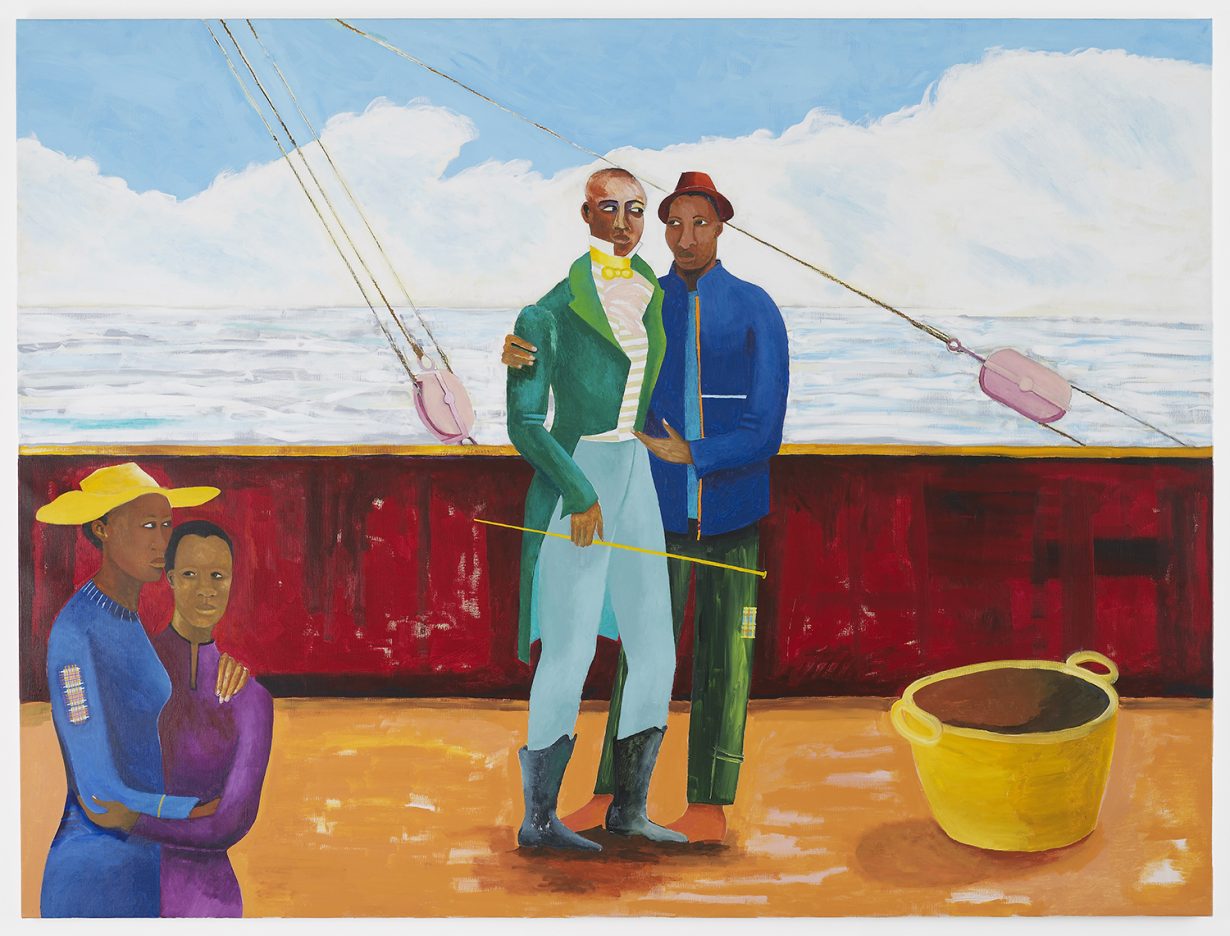

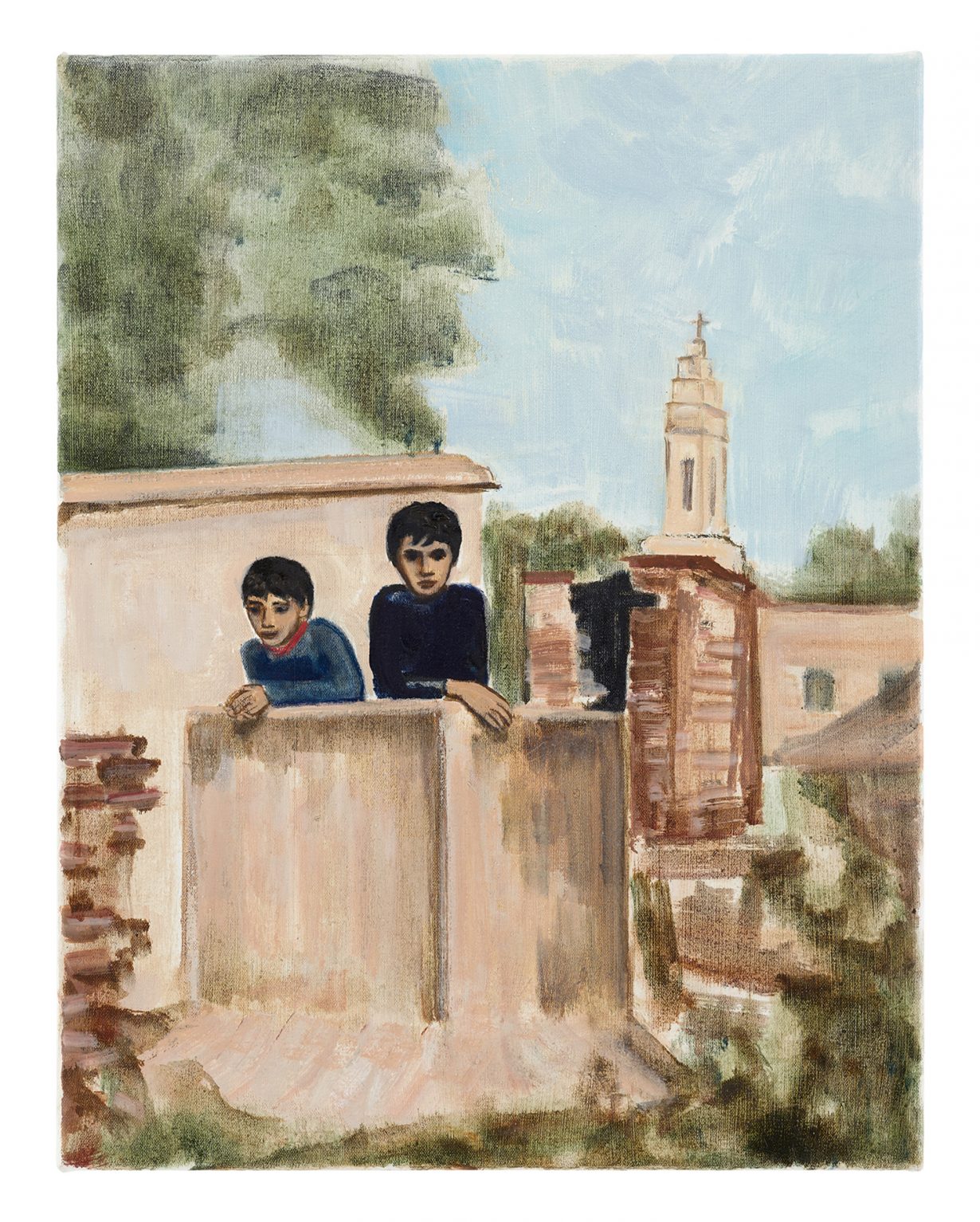

For some, a commitment to traditional forms reflects a desire to engage with and subvert the pictorial history of painting, particularly its alliance with the white male Eurocentric gaze. Lubaina Himid, in The Captain and The Mate (2017–18), riffs on James Tissot’s 1873 painting of the same name, replacing its white sailors with black figures in reference – we’re told – to the infamous nineteenth- century slave ship Le Rodeur, from which 39 African captives were thrown overboard following the outbreak of a mysterious eye disease. Elsewhere, Somaya Critchlow’s sensuous portraits of nubile black women rewire Western tropes of the female nude, calling up references from Renaissance portraiture to 1970s pinups. Conversely, the gentle interiority of the two boys who roam backwoods and explore ruins in Matthew Krishanu’s quietly taut scenes inspired by his Bengali childhood redress the historical objectification of brown bodies by the likes of Paul Gauguin and others.

© Jadé Fadojutimi (2021); courtesy the artist and Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London; photo: Eva Herzog

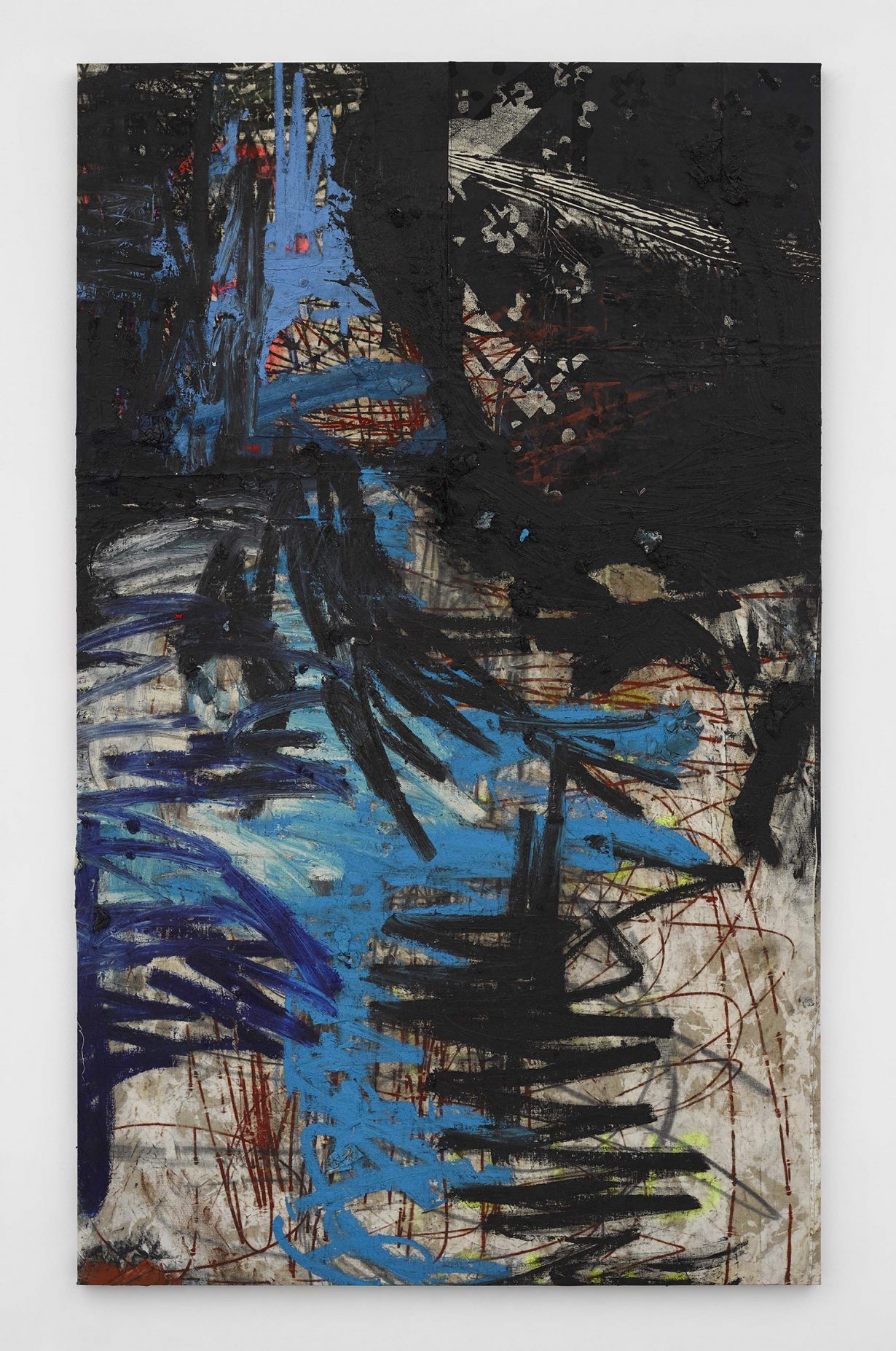

Since many of these artists treat their canvases as sites of assemblage, where references from diverse territories and time periods commingle, the principle of collage provides another possible through-line. Take Hurvin Anderson’s richly textured paintings, which draw on his Jamaican-British heritage to demonstrate painting’s capacity for collapsing time and space. The sense of geographic dislocation and interplay of figuration and abstraction in Anderson’s works owes much to his former tutor Peter Doig, a vastly influential figure who inspired a generation of painters and is represented here by a surprisingly underwhelming selection. Upstairs, in one of the show’s most coherent and satisfying groupings, Oscar Murillo’s moody manifestation paintings (2019–20), with their dense and vigorous marks scrawled onto patchworks of canvas, velvet and linen, meet the gestural, rhythmic lines of Jadé Fadojutimi’s luminous semiabstractions and Rachel Jones’s dazzling, intensely variegated compositions that appear wholly abstract but actually depict flamboyant teeth grills.

Death is a prevalent theme in painting, and many works here allude to life’s fragility: from Graham Little’s decomposing fox meticulously rendered in gouache, to Barrington’s hulking portrait of the recently deceased American rapper DMX, to Rose Wylie’s imposing stealth bomber painted in thick impasto. The spectre of death hangs heavy over the paintings of Iraqi artist Mohammed Sami, who draws on harrowing memories of the tumultuous period following the US-led invasion of his homeland in 2003. The disquieting canvas Infection ii (2021) presents an open door, its dark shadow partially obscuring a poster of Saddam Hussein, leaving visible only the dictator’s upraised arm. In the foreground a green spider plant casts a shadow suggestive of a deadly black widow. Ambiguity prevails: this doorway could lead to death, or perhaps offer an escape to a new life. As for painting itself, death’s door has never seemed so distant.

Mixing It Up: Painting Today

Hayward Gallery, London, on view until 12 December