The Swedish artist confronted gendered biases regarding her medium and the nature of her practice, now celebrated at ICA London a decade after her death

From the 1960s until their separation during the early 1980s, Swedish artist Moki Cherry (née Karlsson) and her American jazz-musician husband, Don Cherry, invented for themselves a pronouncedly countercultural, often itinerant way of living. The spheres of home, school, stage and gallery overlapped as they performed concerts and conducted children’s educational workshops in various venues between the US and Sweden. A photograph shows Don and their toddler son Eagle-Eye wearing Moki’s costumes and playing music in a geodesic dome in which the family lived – as part of an ongoing, participatory happening at the Utopia & Visions 1871–1981 exhibition at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, in 1971. The exhibition-cum-living space was filled with Moki’s psychedelic textile designs and paintings, many of them – such as the mandala she painted on the floor each day – inspired by Eastern religions. Art and life are as if collaged together, their junctures in a state of undulating, improvisational flux. At the ICA, documentation, including more photographs, videos and notebooks, anchors Moki’s practice in its original setting, while the works – including several from her life with Don and subsequent collages and sculptures – testify to her to influence within it.

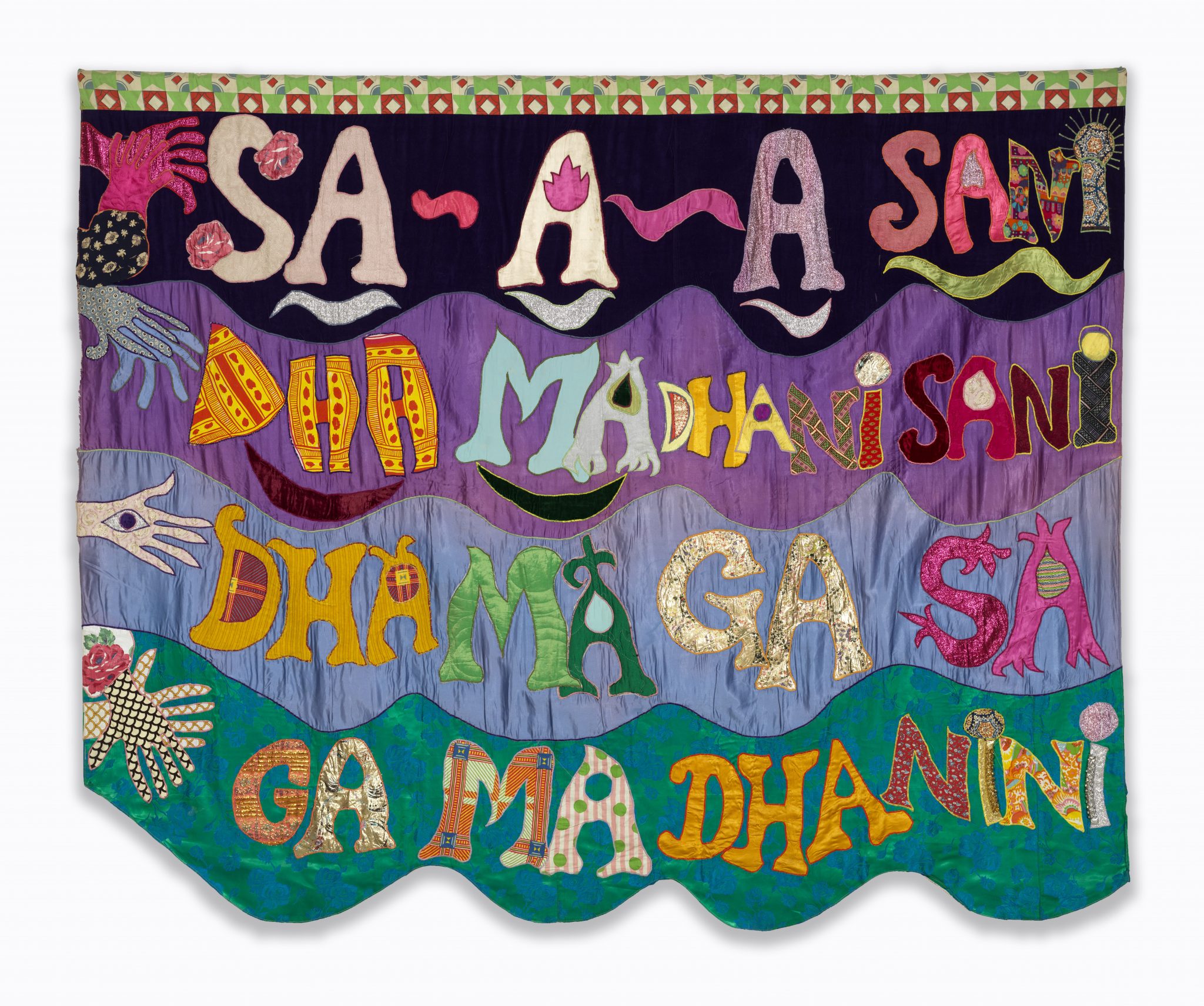

Gendered biases towards textiles as a medium and the holistic nature of her practice – at odds with the ideal of the autonomous art object – downplayed Cherry’s significance during her lifetime, and only in the decade after her death, in 2009, did she begin to receive recognition as an artist. As witnessed here (her first solo exhibition in the UK), Cherry’s work is too forthright to be decorative, its playful, hallucinatory ingenuity actively battling with the limits of sight, sound and touch, and of pictorial and verbal communication: her painting Communicate, How? (1970) features a dazzle-eyed face, with another, saurian creature growing out of one ear, the aural orifice visually transforming into a third eye; D.C (1981), her textile portrait of Don, shows him with an appendaged, dangling tongue and swathes of colour oozing from his ears, multiplying into a pyramidal energy field. Malkauns Raga (1973) epitomises the foundation of her and Don’s collaboration: as the urge to transcend the senses, and beyond language. Used by the couple as a teaching aid, the tapestry rhythmically spells out a raga, an Indian musical form strongly associated with the emotions – and colour – over and above words: in variously patterned fabrics, the lines of (Latin) phonetics surf upon naifly outlined waves of cloth, accompanied by gesturing hands, possibly Hindu mudras, encouraging our bodily participation.

There is joy and disquiet in Cherry’s universe: the trip could go either way, and feminism informs much of her work’s tension: included is a notebook from around 2004–06 in which she wrote, ‘I was never trained to be a female so I survived by taking a creative attitude to daily life & chores’, and this necessitated playful, often humorous rebellion. The skeletal dinner placement in her ghoulish Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1979) – enigmatically flanked by a toy spade and a dart on string, as if we’re supposed to dig and poke at the fabric – could be ridiculing the glitzy romance of, if not Truman Capote’s novella, certainly the film adaptation. In the later photographic collage, Not My Cup of Tea (2006), a woman advertises a sugary vision of domestic bliss, with the insertion of phallic lipsticks and a ‘harmoniously’ entwined man and woman taken from a classical depiction of the Rape of the Sabine Women. Thus she grappled with gender norms, and the stubborn prejudice that making art out of life wasn’t real art.

Here and Now at Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, through 3 September.