The artist’s own brand of conceptual naturalism draws a line between the natural world and human ideals

In the Swiss countryside, there is an ancient Roman quarry that is said to restore the body’s health and induce altered states of consciousness. This place is now named the Emma Kunz Grotto, after the healer-artist who discovered its electromagnetic properties. Kunz (1892– 1963) made hundreds of drawings on graph paper using a pendulum, a device for reading Earth’s vibrations. These works suggest kaleidoscopic seismographs, but to the artist they were tools for divining the imbalances of her patients, which she then rebalanced using the grotto.

Today the Zentrum Emma Kunz runs the grotto, displaying drawings and selling bags of the site’s charged clay, which can be applied to the skin as an emollient or eaten as a tonic: Kunz mixed it into the soil in her garden, then swung her pendulum to stimulate the growth of new plants.

Last September I visited this mysterious cave and stretched out on a flat boulder for the suggested therapeutic period of 30 minutes. (This is what Kunz did to energetically recharge herself.) On emerging I felt intoxicated, disembodied and exhausted, as did my travelling companions. When we drifted back to the Zentrum for a final look at the drawings, Kunz’s pendulous lines now appeared to be slowly thrumming, and so did the world around them. This woozy feeling persisted all day and only lifted the following morning.

Shortly after this journey I went to New Mexico to see and Water, an exhibition by N. Dash at Site Santa Fe. Once I was in the presence of N. Dash’s paintings, I understood that my experience in the grotto had been the right preface to this work, which also seemed to evoke vibrations through its subtle marks and colours. Like Switzerland, New Mexico is a wonderland of minerals, clay and art, and I would come to find a tacit relationship between two artists, underscored by their shared collaboration with earth.

N. Dash’s work begins literally with earth: a thin layer of it spread on jute like a paste. This substrate is then hung on the wall as a painting, raising the ground to eye level as if the artist were tilting the world 90 degrees. Here the viewer can visually meet the ignored material at our feet, which is, in fact, the most important substance of our lives: our food is grown from it, our bodies are made of its fruits and when we die we will sink back into it. Looking closely at this soil, I could see its full complexity: the deep brown glistened with mica and a whole constellation of particulate hues. Atop this layer, the artist paints, prints, carves and sculpturally intervenes, until the character of each work is born.

The exhibition title and Water, seems to be in dialogue with the artist’s previous exhibition title, earth, in 2022 at SMAK, in Ghent. It’s as if this show were completing a phrase, conjoining the two elements that create the primary material of all N. Dash’s work: mud. The process of mixing up the mud – harvested locally in New Mexico – is not unlike making adobe‚ the primary architectural element of the American Southwest and one of the world’s oldest construction materials. Just like this exhibition, an adobe house surrounds you with its minerals, hugging you, like Kunz’s cave.

I saw N. Dash’s first exhibition, in 2012, at Untitled, a since-shuttered gallery in New York City. Back then the artist left the tawny grounds of the works exposed: raw canvas and dirt played the many shades of a coffee-coloured rainbow. Seeing N. Dash’s work there for the first time, it looked like a fresh contribution to the history of umber art, from Rembrandt to Walter De Maria to Ana Mendieta to Antoni Tàpies. Kunz, too, grounded her visions in terra firma hues, working on tan paper and scribbled sepia backgrounds. Atop this, her botanic, bifurcating patterns pop with the contrast of flowers against loam.

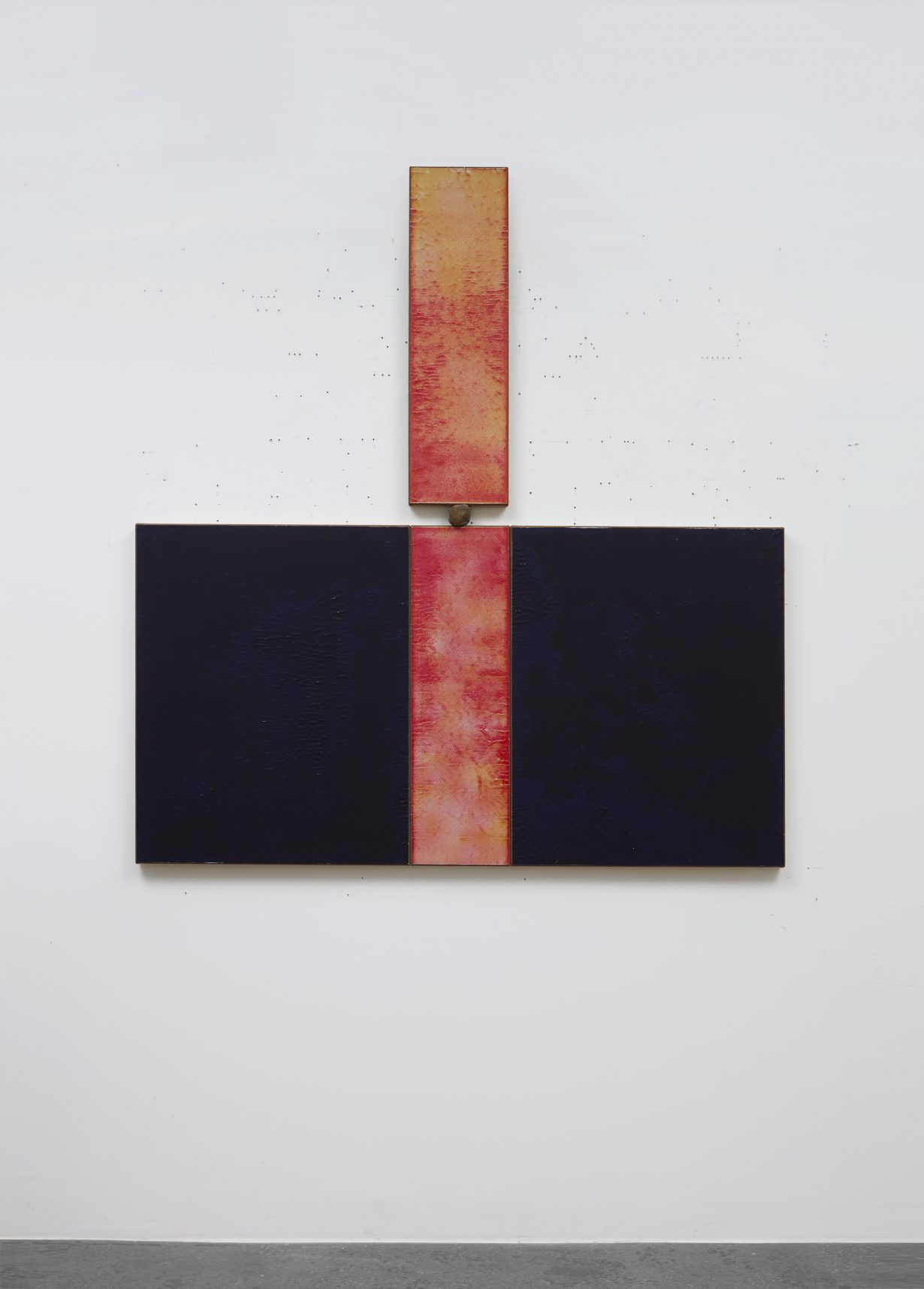

In the last decade N. Dash’s colours have also bloomed from mud, and New Mexico (the artist’s onetime home) seems responsible. and Water contains the muted green of local sage and the cobalt of the Rio Grande. One wall of deep and dark-toned works suggests the high-desert night, oil-painted and screen-printed in a spectrum of violets and sidereal glints. Another wall of sun-faded colours renders an arid afternoon, cracked and bleached. For one work, layered rosette patterns of cyan and solar-yellow stimulate the same kind of psychedelic, visual buzz as lichen on a boulder, or as the hypnotic forms of a Kunz drawing. In all these works, the mud is almost fully occluded by colours, and is only revealed as it seeps from the edges, like tar oozing up through the sandstone.

Here, at the surface, the paint and soil marry into a single terrestrial substance. This is an alchemical mixing with paint, ink, acrylic and oil, as if the artist were suggesting some new kind of hybrid anthro-soil. A network of marled fissures and errant marks complicate these surfaces, turning fields of colour into weathered patches of the planet’s crust. I think of this as ambient landscape painting, which is underscored by how N. Dash spreads actual landscaping throughout the space: a reptilian stone sits at the threshold, and another is wedged between two canvases, as if holding the whole piece together.

Likewise, Kunz’s mandala abstractions are ambient portrait paintings, without a hint of human resemblance. For each drawing, she would lay the paper on the table before her patient, and in a single session document their humming essence. She was not some misanthropic, cave-dwelling environmentalist, worshipping Earth while reviling humanity; she was a visionary who sought to find the most basic natural forces within every individual.

N. Dash’s works also refuse the ideological purity of nature, free of human touch. Almost every work contains human artefacts – plastic netting, cardboard packing-corners, Styrofoam blocks, plastic water bottles – much of it the detritus of a functioning artist’s studio. In conversation, N. Dash refers to these elements as “provisional architecture”, bits of material that seem to turn canvases into structural forms. As I looked upon the paintings I began to think of them as the panels of some speculative adobe monolith, standing alone, in a desert of the future.

For me, this kind of imaginative play is essential to engaging with these paintings, since the artist presents objects with little indication of process or identity. Dash’s exhibitions are often self-titled, explanatory text is limited or entirely forgone; pronouns are avoided; and individual works are untitled or tagged with seemingly random numbers and letters, as if the artist were an archaeologist, cataloguing discoveries with an index. Even the artist’s name withholds, suggesting punctuation – a breath between thoughts – a hovering horizon.

A dash is also, of course, a line, and line is essential to N. Dash’s work. These are paintings but the artist also considers them drawings, if unconventional ones. Here, N. Dash shares Kunz’s innovative approach of producing lines without the pressure of a brush or pencil. Instead, both artists use a kind of sculptural line in space: a taut string. While the older artist harnessed the planet’s gravity and swinging momentum, N. Dash buries string into the painting, as if marking the territory of an excavation site. N. Dash does not cite Kunz as an influence on any of these choices, but the subtle resonances between the artists grows naturally out of their shared fascination with earth.

N. Dash feels that “receptivity to certain frequencies” is where the work begins, a statement that could have come from Kunz. In a rare revelation of process, N. Dash discusses the origin of the silkscreen images on many of the works: holding a small square of fabric, the artist rubs at it, repeatedly, daily, until it disintegrates into a nest of fibres, or strings, or even, as it were, lines. This process happens throughout the day, during conversations, walking down the street and at home alone. It’s one way of recording the many varied vibrations of human touch – what the artist thinks of as “information, both material and immaterial”.

For me, N. Dash’s resistance to language is a means of drawing attention to these ineffable, etheric aspects of the work. The artist is accumulating a swatch of stored, potential energy, and once the fabric is nearly eroded, the remnants are photographed and printed onto the work. What results is that same concentrated energy, now fully kinetic, looking like expanding celestial nebulae. These images capture the great illusion of abstraction – the way a plume of clouds or craggy hillside can, for a moment, resemble an impossible form of life. This is how an intimate, finger-size gesture transforms into a vast, open landscape.

In many ways and Water points to the land surrounding the show, a place of dryness, limited resources and artists. There is a strong lineage of artists who have lived and worked in New Mexico – Agnes Martin, Bruce Nauman, Richard Tuttle, Meredith Monk, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge and Emmi Whitehorse – and their work, like N. Dash’s, plays out the relationship between the natural world and the ideals of the human mind: a kind of conceptual naturalism.

It’s like what happens when a house appears in a formerly untouched wilderness. An explosion of contrasts is ignited: harmony and dissonance, creation and erasure, grid and grass. When we look at this scene, all these polarities must be held together, at once – and the more we look, the more fraught and beautiful it becomes, as if the entire drama of human history could be told in the simple meeting of dirt and line.