The VIP orchid programme, often dubbed ‘orchid diplomacy’, started in 1956, when Singapore was still a British colony

In December 2016, Rodrigo Duterte, then the president of the Philippines (now at the International Criminal Court at the Hague awaiting trial for crimes against humanity for his murderous ‘war on drugs’), went on a state visit to Singapore. At that point he had been in office for just six months but had already extended to the whole country the extrajudicial killings that had been the trade-mark characteristic of his previous war on drugs in Davao City, where he had been mayor for 22 years. Once in Singapore, the president visited the dreamy National Orchid Garden, nestled inside the city-state’s jewel, the Singapore Botanic Gardens. Here, he was ceremoniously presented with the Dendrobium Rodrigo Roa Duterte, a blood-red orchid. It was hybridised at the Botanical Garden, by combining a Dendrobium Wendy Levene and a Dendrobium Urmila Nandey. Dendrobium is the name of one of the largest orchid genera – with more than 1,800 species – which, in the wild, grows on trees (in which case they are known as epiphytic orchids) or on rocks (lithophytic orchids), getting their nutriment from the air, the sun and rainwater. Dendrobium is a composite word from the Greek dendron, which translates as ‘tree’, and bios, which translates as ‘life’.

One year and three months later it was Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s turn to go to Singapore on a state visit: on 13 March 2018, in the very same National Orchid Garden, she was presented with Dendrobium Sheikh Hasina, which had been created through hybridisation of the Dendrobium Sunplaza Park and the Dendrobium Seletar Chocolat. It is a slightly more complex flower, when compared to the blood-red petals of Duterte’s specimen: the Sheikh Hasina, thanks to its Selatar Chocolat ancestry, has a vague mahogany colour, with light-brown sepals lined with a very thin white margin. Dark maroon and purple hues dot the small bunches of tight-knit flowers that characterise this particular orchid. The former prime minister is currently in exile in India, after fleeing Bangladesh in August 2024, when her 15-year reign was brought to an end by mass street protests, during which up to 1,400 people were killed by authorities under her command. In November, Hasina was given the death penalty in absentia, as retribution for the deadly crackdown that she requested.

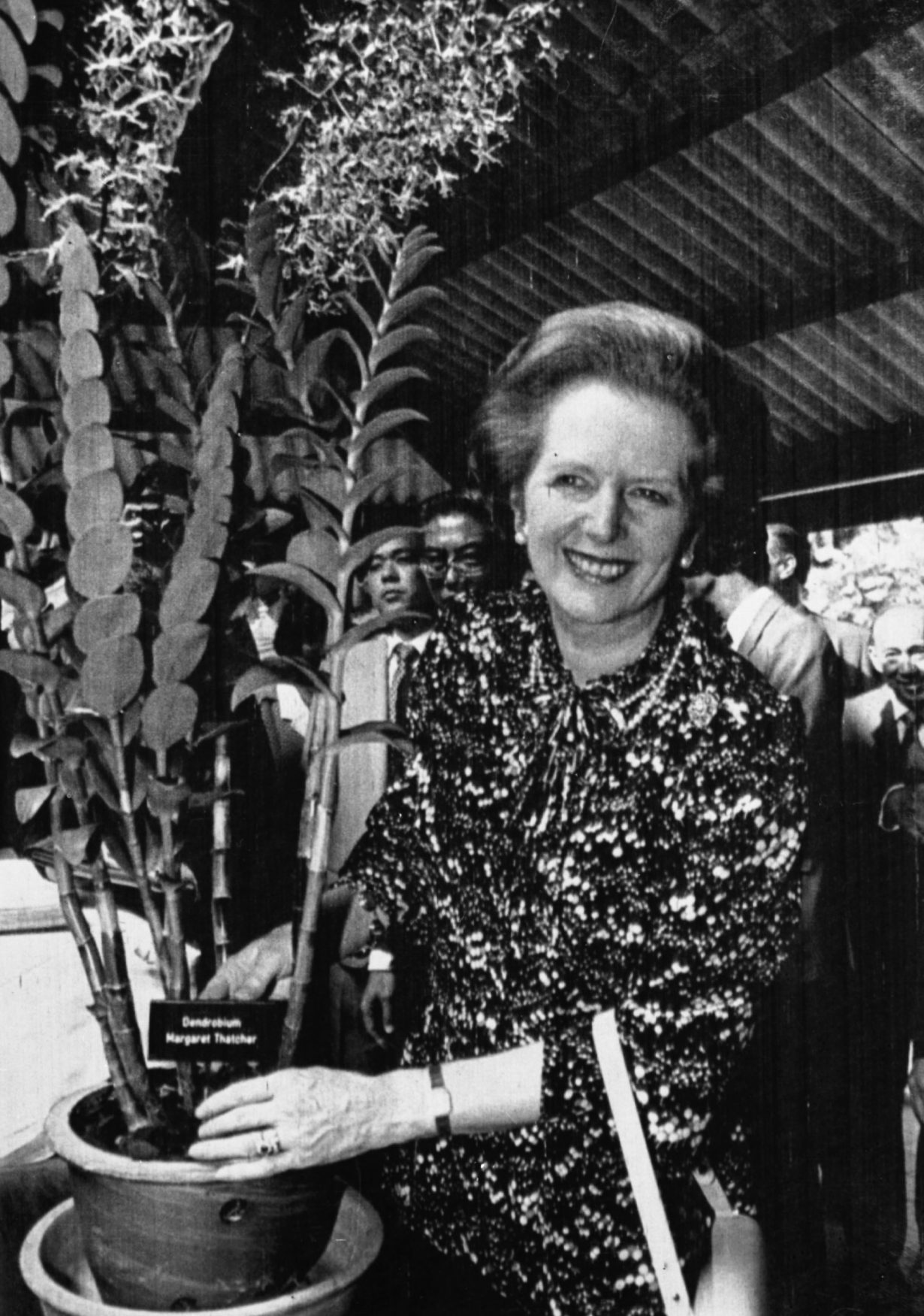

Now that the violence of their namesakes has been brought before the courts, the two Dendrobiums, according to a source who works at the Botanic Gardens, will most likely just be ‘ignored’ and other leaders, and their orchids, will be given a more prominent display. The National Orchid Garden has thousands of varieties of orchids, some in special humid greenhouses, others in the open air, and they are often rotated, to allow visitors always to see only those that are in full bloom. Inside the orchid garden there is a smaller section, called the VIP Orchid Garden, arranged on a little looping path, with flowers on either side and in the central island, which is where the orchids named after world leaders and royalty who have gone to Singapore on a state visit are located. Some, like the Margaret Thatcher, are on display most of the time – this orchid is also a Dendrobium, fuchsia, white and yellow, with the upper petals twisted in a rather spikey, hornlike shape, not without parallels to a certain harshness of character of the former British prime minister. Joe Biden has a his-and-hers orchid, called the Joe and Jill Biden, a purple Dendrobium, but so does Kamala Harris for when she went to Singapore as his vice president and was presented with a purplish-pink Papilionanda Kamala Harris, a hybrid of a Vanda Kulwadee Fragrance and a Papilion-anthe hookeriana, a type of orchid with long, thin leaves. Nelson Mandela and Barack Obama too have Papilionandas to their names: the Sealara Nelson Mandela, in particular, is a very attractive hybrid between a Mas Los Angeles and a Paraphalaenopsis labukensis, with yellow flowers, delicately dotted with a pinkish orange on the inside of the petals. Not all the VIP orchids are named for politicians, however: a little side spot is designated the Celebrities Garden. Here, the late Jane Goodall has a Spathaglottis named after her, a yellow orchid with a star-shaped flower, with just a scattering of maroon on the petals. During one of Hong Kong actor Jackie Chan’s visits, he was also immortalised via a Dendrobium, in bright magenta. The lower petal has a shape that is described as similar to a dragon’s nose, a form seen as quite suitable for a martial artist. It’s hard to think of a garden – so dedicated to smoothing political relationships and the polishing of egos – that is more political than this one.

The VIP orchid programme, often dubbed ‘orchid diplomacy’, started in 1956, when Singapore was still a British colony. Lady Anne Black, wife of the former governor of Singapore, Robert Black, was gifted an Aranthera Anne Black, a hybrid of an Arachnis Maggie Oei and a Renanthera coccinea; it was the first orchid named after a political personality, even if a domestic one. After Singapore, as part of Malaya, gained independence from London, in 1963, and after Singapore was expelled from Malaya and became the current city-state, in 1965, the ‘orchid diplomacy’ project got fully underway. Singapore was to use nature as a political tool, wrapped in the gentleness of flowering plants and in the harshness of commercial hybridisation programmes. Two years later, in May 1967, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew introduced his idea of Singapore as a ‘Garden City’ – a city rich in green spaces, of which he was to be the Gardener in Chief, according to his own definition. Gardening metaphors started to flourish in his political speeches, but there is no reason to think that he wasn’t a true nature lover. In 1968, after a trip to Boston during which he was particularly impressed by the clean air, which he attributed to the trees lining the streets, he introduced a further plan, which required everyone to plant as many trees as possible. Tree Planting Day was established (it is ongoing) even if it did have some initial teething problems, with students and officials planting trees too randomly for them to survive. The programme was eventually rationalised, and greenery in Singapore is decidedly luxuriant, omnipresent and extraordinarily beautiful.

In colonial times, the Botanic Gardens in Singapore was one of the most important ‘economic gardens’, run as a semi-extension of the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew, outside of London, and used to classify and select plants that could have an economic return for the British Empire. It was in Singapore, for example, that the first director of the botanical gardens, Henry Nicholas Ridley, in charge from 1888 to 1912, introduced the ‘herringbone’ rubber tree tapping system, which involves making a shallow cut, in a herringbone shape, in the trunk of the tree, guaranteeing a good flow of sap without cutting too deeply.

Courtesy National Museum of Singapore, National Heritage Board

Hybridisation of orchids was, and is, another commercially successful enterprise. Walking to the Micropropagation Laboratory, visitors can see, through large glass windows, four separate areas in which the orchids are developed. There is a Media Preparation Room, where the plant culture media is readied; a Transfer Room, where the plants get transferred to different culture vessels in a sterile environment; then the Shaker Room, which is undoubtedly the most peculiar one, in which the developing plants still inside liquid media Singapore was to use nature as a political tool, wrapped in the gentleness of flowering plants and in the harshness of commercial hybridisation programmes are placed on shelves that shake constantly in a gentle round motion, meant to ‘confuse’ their sense of gravity and delay the separation of tissues into roots and blooms, so as to increase the chances of maturation of a new hybrid into a fully formed and viable plant. The last room shows the successful plants growing steadily in little covered bottles (no longer shaking) in the Culture Room, already in soil-like solid media. This laboratory, itself a hybrid of nature and technology, was founded by Eric Holttum, director of the garden from 1926 to 1949, and very enthusiastic about developing the orchid hybridisation programme – even if he doesn’t seem to have thought of the political and diplomatic potential of this exercise.

The factorylike system makes sure that at any point in time the garden has at least a few hybrid orchids either ready or nearly ready, so that when the protocols for a state visit to Singapore are initiated, the garden can send along the photos and qualities of the viable orchids for the official dedication. The diplomatic team in charge of the visit in the foreign capital will receive these documents and, possibly with the head of state in question, select the most suitable flower, which will then be presented as part of the diplomatic ceremonies, during the customary visit to the National Botanical Gardens of Singapore.

Here, with well-stroked egos, the orchid diplomacy programme ends. The flower, with its new name, is enshrined in the records and, on rotation, displayed in the VIP section of the Orchid Garden. Should the head of state engage in programme of extrajudicial killing, as Duterte is alleged to have done prior to 2016, or bloody their hands afterwards, the orchid might simply subtly slide to less prominent spots in the garden, and then not be put on display anymore.

Recruiting nature to diplomatic service, after all, unavoidably means asking it to flower in front of unsavoury politicians.

From the Winter 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next Charwei Tsai: Touching the Earth