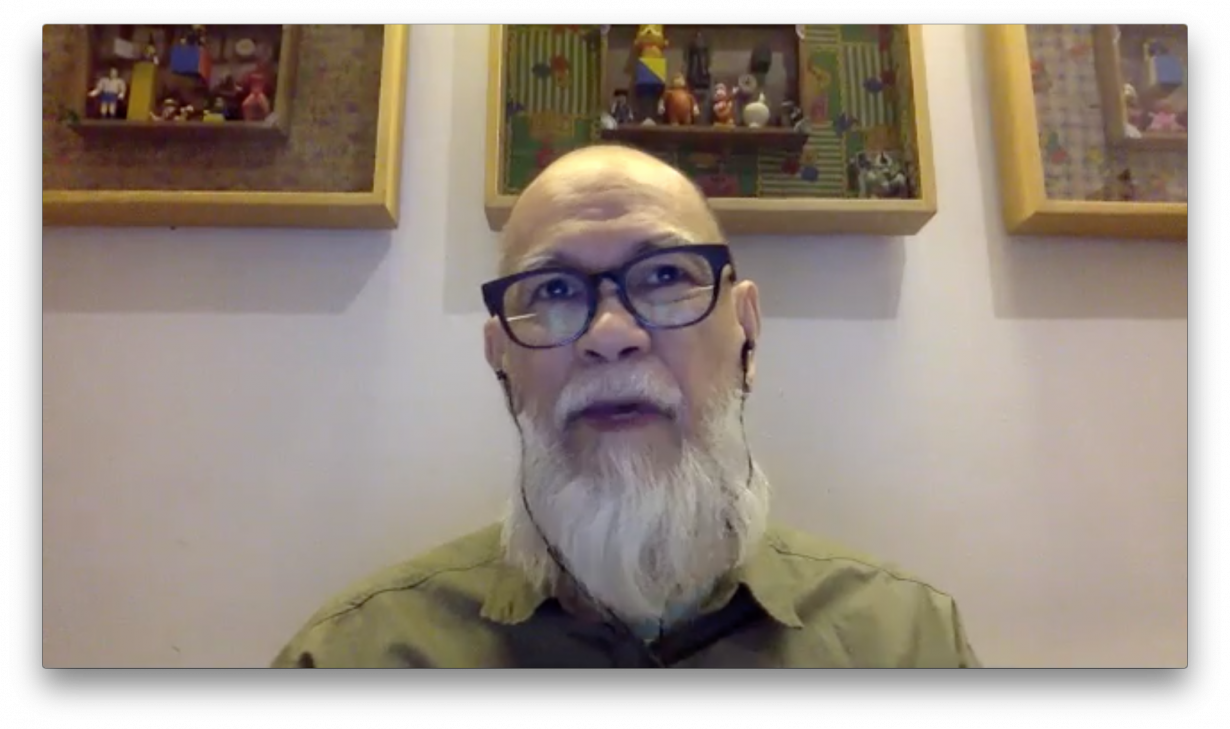

Norberto ‘Peewee’ Roldan is a multimedia artist and curator, and currently the artistic director of Green Papaya Art Projects, a multidisciplinary platform in Quezon City that was founded in 2000 and is scheduled to close at the end of this year. He has worked at the forefront of cultural artistic practice in the Philippines, having founded the seminal artist group Black Artists in Asia in 1986 (a Philippines-based group focused on socially and politically progressive practice) and initiated the country’s longest-running biennale, VIVA EXCON, in the Visayas region. Roldan’s work offers commentary on the social, political and cultural conditions of the Philippines.

MARV RECINTO Art can sometimes be perceived as secondary in Western culture: premodern art; it’s often viewed as mimetic, as a mirror of society and sort of a copy, and in that sense a secondary fact. Do you think art has the ability to facilitate change? Whether it be for workers, for artists or for art itself?

NORBERTO ROLDAN I think the role of artists and cultural workers has changed dramatically over the years. It may be true that in the early years of the protest era, artists were just there to mirror society and come up with protest songs and reflect the misery of the people in the form of theatre and all that, but what we’re observing now are artists and cultural workers who are entrenched in organisational work with other organisations in other sectors: taking part in policy formulation, planning on how to advance a resistance movement against a despotic regime, for example. Artists are no longer there to reflect history or what is happening in the country, but to be active participants in political actions.

MR In the Philippines, artist organisations and artist groups have had a long history of this, and I think it’s important to contextualise that in order to talk about the present. Perhaps we could start by talking about some of the most significant art groups during the Marcos era [1965–86]?

NR I think the most prominent group during that time was the Kaisahan group [‘Solidarity’ in English, founded 1976], the group that precipitated the Social Realist [SR] movement. I must say that the movement was not just influential during that time, but remains so up to the present generation of young SR practitioners, so to speak. Alongside visual arts during the Marcos era, street theatre was a very, very popular form of resistance. It was made popular by PETA, which was able to organise a community of artists and network of theatre organisations all over the Philippines. In fact, alongside the Concerned Artists of the Philippines [CAP ] in Negros [the Philippines’s fourth largest island], the Negros Theater League was one of the most active cultural organisations at the forefront of the resistance movement. During the 1980s, CAP was organised by a prominent fi lmmaker, Lino Brocka [who died in a car crash in 1991], and for a time, during the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, CAP took a hiatus, but in recent years it was reorganised, and it’s now one of the active organisations alongside other new and younger ones in the cultural front.

MR I was just going to name some of the other organisations, like SAKA, RESBAK, Simbayan, that have taken a big stance in the current era.

NR I mentioned earlier that artists are not just involved in the production of artistic work, but they’re also very active in community work and organising. The work of an artist now is not just contained in producing an artwork, but has gone beyond productions of ephemeral works to encompass rallies and marches.

You mentioned SAKA, for example. SAKAis basically an alliance of artists aligned with the farmers’ sector. They advocate for a genuine agrarian reform and rural development. They have gone all-out to assist farmers in cultivating idle lands and in leading urban farming even before the pandemic struck in March. This is why I feel that the work of artists and cultural workers has become more important, because our communities have become more responsive to them and have been more open to them, whereas before artists were just looked upon as coming into a particular community to entertain.

MR I wanted to ask you about Joseph Estrada [a former actor who served as president of the Philippines between 1998 and 2001] and his impeachment in 2001. You started Green Papaya in 2000. How was Green Papaya involved with this?

NR On the day that thousands of people were massing in front of the shrine during EDSA II [the Second EDSA Revolution; the first, also known as the People Power Revolution and commemorated by the shrine, had led to the Marcoses’ departure in 1986], we were supposed to open a solo exhibition by Santiago Bose in Green Papaya. We heard over the radio that thousands and thousands of people were already at the EDSA shrine. And Santiago said, “Hey, why don’t we cancel the opening and bring all the food to EDSA?”

During that time, Surrounded By Water, another independent art space run by a collective of younger artists, was running a space right across the shrine. When we got to EDSA, bringing all the food from the opening, artists from our network were already there. Again, that was an action where artists were seen as important participants in that particular rally because artists had started to mobilise the immediate crowd within the perimeter and started to solicit food, gather this food and distribute it to people. These are non-art-related actions, but nonetheless artists were there to make their presence felt as part of society and of the community.

MR Do you think that artists and artist groups have an obligation or duty to be involved with politics or the wider parameters of the world rather than being insulated in the perceived ‘fine-art world’?

NR I don’t think there is an argument about whether or not artists, first and foremost, are citizens. You’re a part of your community and you’re a part of a larger society. Society develops. You cannot escape being a part of it. I think it is incumbent on every individual, artist or non-artist, to participate in social transformation. In fact, all the more so if you are an artist.

There is a need for artists to contribute creative solutions to the fundamental problems of society. They read things in different ways and they offer solutions like any other. I think it may be sad to note that not all artists are political, but even artists who profess to be apolitical cannot escape the fact that choosing to be apolitical is in effect a political action.

Let’s take, for example, RESBAK, born out of the need to respond to the killings that took place as part of Duterte’s ‘drug war’. What the artists are trying to say is, if you are aware of these killings and if you’re aware that these are extrajudicial killings and you keep silent about them, you either condone the killings and take responsibility for all these crimes, or you take an action against them. There seems to be no middle ground when it comes to something that really affects the whole community, the whole society.

And this brings me to how I got politicised. I got married in the early 1980s and I was obliged to go to Negros to cultivate a sugar farm that my now ex-wife had inherited. My ex-father-in-law had said, “You’re crazy if you insist in working in Manila when your wife has a farm.” So I went to Negros, and for the first time in my life I was exposed to what you usually read in papers about the prevailing feudal system – the sugar barons – and the exploitation of sugar workers. I just couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the reality. It was a moment for me to decide whether I stay there and fight for the rights of these people, or get off the island.

That’s how I got involved with CAP and got myself into what was part of the resistance movement during the Marcos years, which also led to my leaving the country between 1987 and 89, for security reasons.

MR You went on to form Black Artists in Asia after the Marcos years and during the uptime of rebuilding.

NR Black Artists in Asia was organised as a way to get the artists out of this dilemma of having been part of CAP in Negros. During the early part of the 1980s we visual artists were pretty much involved with the propaganda movement, putting up banners and murals almost every time there was a rally going on in the island. We never had a chance to practice individually as painters. When Cory Aquino took the presidency, most of the members of CAP thought, “Hey, Marcos is out. Why don’t we try to invite galleries and kickstart our own individual practices?” Black Artists in Asia was a kind of strategic formation for all the progressive artists to still be together, but no longer part of the larger movement of the National Democratic Movement.

MR Let’s jump to 2020 then. Obviously, a difficult year for everyone globally. In the Philippines Duterte still holds the presidency – until 2022. It seems like there was a lot of activity with artist groups and cultural workers, especially with the protests against shutting down ABS-CBN [a national independent television network] and the antiterrorism law. Let’s talk a little bit about what influence the arts groups had then and what sort of change they’re able to effect, or continue to effect.

NR When there was an attempt to shut down ABS-CBN (before the actual shutdown), CAP came out into the open to generate support and to resist the closure. Considering that ABS-CBN has its own stable of artists, stars, actresses, there were only a few of them initially who actually went out of their way to expose themselves in this way. Eventually, more and more of them started to feel, “Hey, this is our home, we need to protect it”. But on the other side of the line are pro-Duterte stars and celebrities who kept to their lines and loyalty to Duterte. Now we have seen them moving to other networks. Loyalty to Duterte is not so much on ideological grounds, but more on personality…

MR Like Trump.

NR Exactly.

MR I guess there’s also a sense of self-preservation, which is entirely understandable.

NR That is the theory offered by analysts on why Duterte still gets a 91 percent approval rating. There’s only one way to answer that kind of survey if you don’t want to endanger yourself. But with the Trump administration out of power soon, I think the climate in the Philippines will change naturally.

MR There’s a reverence towards American culture in the Philippines. If they see this is the turn, hopefully it’ll permeate there as well. I think a very important question to ask, because we have been talking about what power artists and artist groups yield, is where they’re perhaps lacking. What could be improved, what are they lacking and where, going forward, do you see power in artistic groups?

NR There is an anticipation for the National Commission for Culture and the Arts to become an independent Department of Culture. Still under the government. But what we’re seeing, based on the development of this project, is that there are less artists involved in the discussion and there are more technocrats and people in government who are crafting the structure and the policies of this department. I believe that there should be a substantial participation of artists, since this particular department, after all, will be all about them. Over the last 20 years we’ve seen more sectoral representations in Congress, where the representatives are not elected as personalities but as organisations, like Bayan Muna, where they then elect their own representative. It has not been applied to the arts and culture sector because a sectoral party, up to now, has never been organised.

I think the reason for that is also that art communities in the Philippines or in Manila are very, very diverse and have different agendas and schools of thoughts. It’s like dealing with a hundred different barangays [the smallest administrative districts in the Philippines]. I think that is the weakness of the arts sector, because it has not achieved a common vision on how arts and culture should proceed, should be developed and should be supported in this country. I feel sorry for that.

Marv Recinto is a writer based in London