Why faulty first impressions only tell half the story, and the beauty of never quite making up your mind

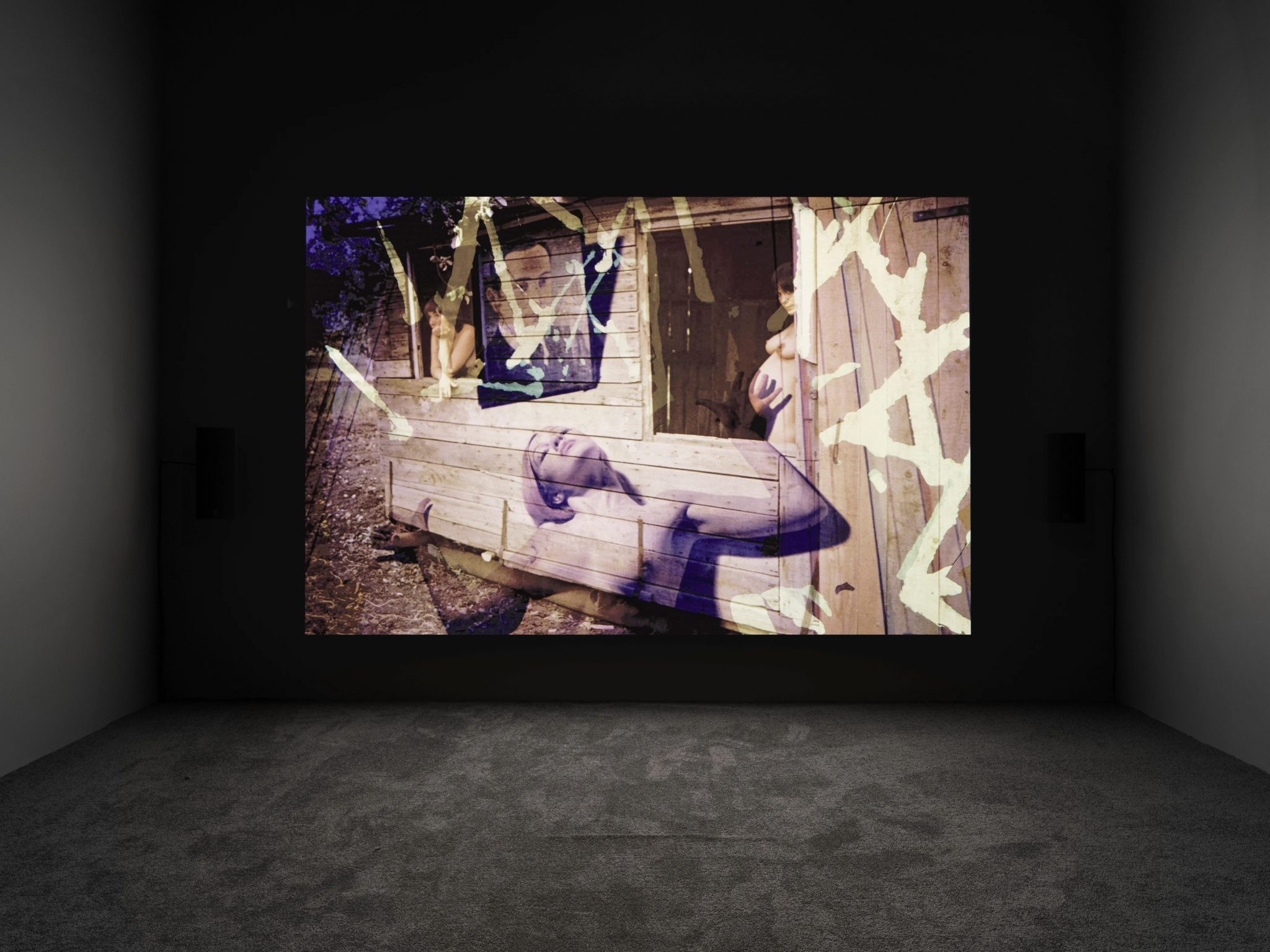

I disliked Boris Mikhailov’s exhibition at Marian Goodman on my first visit to the gallery’s new Tribeca location, where I watched two of the Ukrainian photographer’s videos on the first floor. I found the experimental language, especially in Yesterday’s Sandwich (late 1960s–70s) –a ten-minute montage of surrealist images made from superimposed slides of his photos, set to Pink Floyd’s Breathe (In the Air) (1973) – stale and off-putting. Practically every other slide featured a sensuously posed and unidentified nude woman. One sat on a boulder with her legs raised, her chin tilted back, her image superimposed on a mountain landscape. Another, with her eyes closed, breasts bared and arms raised, was overlaid on the exterior of a cabin in whose windows stood two more unclothed women, one heavily pregnant. Even given the Soviet Union’s history of censoring pornography, the nudity here felt bathetic rather than politically transgressive.

But February wound up being a lesson in slow looking, a month marked by repeat visits to exhibitions, conversations that grew in fits and starts, and faulty first impressions brought into focus over time. When my date dragged me back to Marian Goodman, I realised I’d missed the entire second floor of the gallery. There I found three of Mikhailov’s photographic series, one of which, titled By the Ground (1991) – sepia-toned gelatin silver prints made on the streets of Kharkiv and Moscow the year the Soviet Union fell – stopped me in my tracks. In this work, women were not only objects of the viewer’s gaze but also the ones looking: spying on others’ property, seeing into walled-off urban areas. One, shown from the back in a trench coat and heels, steps onto some rubble to peek over a wooden fence and into a yard. Another peers through the narrow gap between two segments of a long, pale partition, her companion watching from behind, neither of their faces visible to the camera. An elderly figure in a baggy dress, standing in the shadow of a tall industrial gate, seems to wait for someone or something to materialise in the crack between the metal panels. Where Yesterday’s Sandwich had seemed to me too saccharine, these photos had a coolness about them, accentuated by Mikhailov’s choice to shoot from the hip with a horizon camera, creating wide and lonely panoramic views.

Another good second impression: Flint Jamison, known enthusiast of plastic pipes and information flow, had concurrent exhibitions titled Class: Weight and Installation View at Miguel Abreu’s two Lower East Side locations. Both featured sculptures made to explore what the press release described as ‘the lack of data concerning an artwork’s weight’ in institutional archives and galleries’ inventory software. A large triangular structure in the first space caught my eye. Jersey Barrier Mold (2025), an 86.6kg wooden frame resembling a form for moulding concrete, unlatched and open on the floor, referenced the modular walls installed on highways to prevent head-on vehicular collisions. Another large and car-related work in the second space, Installation View (2023/25), a 67.6kg garage door that the gallery attendant could open and close with the press of a button, was made of fir and purpleheart and placed behind sculptures resembling a domestic entertainment system. The garage door opened onto a sterile white wall; in the first space, motorised shelves slid up and down, portable power stations whirred and there were ample allusions to the transportation of artworks, but nothing – not even the air – seemed to circulate.

On opening night, I’d thought the round-ended, roughly centimetre-wide grooves found all over the wood on Jersey Barrier Mold, Installation View and Jamison’s other sculptures had been made by the artist; I’d referred to them as “scratches”. It wasn’t until later, while scrolling through photos on my phone, that I noticed how deeply the grooves were incised in the wood and was struck by a spell of trypophobia. I returned to the gallery’s Eldridge Street location and picked up one of the artist’s ‘maintenance manuals’ for the works, which informed me that the grooves were made not by the artist but by worms. Jamison had sourced the ‘worm-infested fir’ from an estuary in the American Northwest. The worms were gone now, but I could still imagine their bodies boring through the sculptures, the traces of their movement reinstating organic action – not labour per se but something wilder – to the material manifestations of Jamison’s conceptual propositions, which grew more unnerving the closer and longer I looked.

Then there was Studio Wenjüe Lu’s Portraits of Aufhebung, a sculpture exhibition-slash-clothing collection launch at Komune, a store in the Lower East Side. An invite had landed in my inbox; it wasn’t my usual beat, but I decided to pop in because I was already nearby. The event was so crowded that I couldn’t get a good look at the clothes – all creamy beige, the colour of unprimed canvas – or the beige cotton and polyester soft sculptures sitting next to the garment displays. Instead I got into a long conversation about linguistics and philosophy with one of the studio’s cofounders, Michael Fang, during which I was distracted by his DIY baseball cap, made from half of a camo Kamala Harris hat and half of a red Trump hat. The garments, I gleaned, were made to fit the cartoonish sculptures before being scaled up to fit humans.

Afterwards, I paid a visit to the designers’ Williamsburg studio, where their sculptures hung from the ceiling like decommissioned automata. Some were bulbous, others distended; some were pitted like moons and others antennaed like microbes. Most had small pert hands and feet but no heads. They hung above racks of shirts and pants, all crafted as per the designers’ minimalist palette. Fang played music, made tea and sat with me while the other half of the duo, Wenjue Lu, stayed on her feet, traversing the studio and taking photos of their garments one by one, the sound of her camera punctuating her partner’s sentences. The pieces she photographed looked intimidating. Their silhouettes were complicated, ambiguous; I surmised they’d be difficult to put on, even harder to style. Much like at the opening, Fang seemed more interested in discussing philosophy than introducing me to the clothing and the creaturely forms that surrounded us – ‘humanoids’, he called them. I left intrigued by the ways in which these two, with their multidisciplinary practice, seemed intent on devouring everything from the desire and mystification of fashion to the academic aspirations of fine art to the everyday exigencies of practical use.

Their brand still felt opaque to me, though. It wasn’t until I returned to Komune and actually tried on pieces from their previous year’s collection that I began to recognise their sense of humour. Dressing myself in an earth-toned, semitransparent linen shirt with wrinkly round patches, irregularly spaced buttons and overlong sleeves that swallowed my wrists and hands – evoking a languid, gangly-limbed sculpture the designers named Mannequin .4 (2022) – I, too, felt looser. Donning a pair of their baggy linen trousers, I felt like I was climbing into a burlap sack with a crinkly inner lining. Before the mirror, my legs morphed into two fusiform tree trunks. But I was surprised to find the silhouette neither intimidating nor unpleasant. I suspect the whole initiation process had been necessary for just that.