How the recent tendency for ambiguous self-reflexivity is redrawing the lines of institutional critique

Even for those not directly affected by the recent fires, whether those that spread widely across Los Angeles or the blaze in Tribeca, Manhattan, which damaged two of the neighbourhood’s galleries, it may feel like an indulgence to complain about hackneyed exposés and interventions in New York’s art scene. The new year began with Dean Kissick’s ‘The Painted Protest: How politics destroyed contemporary art’, published in Harper’s last December, still lingering in the air, as the critic was tapped for a number of speaking engagements in January, which included appearing on a panel at the SVA Theatre with the hosts of the Red Scare podcast. Much of the commentary around Kissick’s essay has focused on how art institutions have gone too far in promoting social justice; meanwhile, ironically, protesters have been calling out the Brooklyn Museum for refusing the requests of exhibiting artists who had asked to hang keffiyehs next to their works in a gesture of pro-Palestine solidarity (following the Noguchi Museum’s keffiyeh ban last year). With institutional critique on display around the city, such as in Michael Asher’s posthumous survey at Artists Space and Jenna Bliss’s film True Entertainment (2023), a parodic art fair ‘reality show’ screening at Amant, self-reflexivity has become something of a fait accompli for artists working with New York’s museums and nonprofits.

I spent January mulling over two artworks: one by Cameron Rowland and the other by Wong Kit Yi. At the start of the month, I went upstate to ‘see’ Rowland’s Plot (2024) at Dia Beacon, which forms the focal point of a solo exhibition, Properties. The work consists of one acre of land, roughly triangular, located just beyond the museum’s northeastern corner. It is bound by a creek to the south and Dia’s property line to the north. Visitors cannot access the plot but can peruse a diagram of it in a ten-page document that has been framed and hung on the wall. The document, notarised and signed by Rowland, Dia’s director and the county clerk, represents the transfer of the land from the institution to the artist. In an accompanying text about the work, Rowland notes that unmarked burial sites for African people forcibly brought to the United States as part of the transatlantic slave trade are frequently discovered in New York State and that developers nevertheless build on these sites; the artist argues that a mass grave might exist on Dia Beacon’s grounds and has therefore barred the foundation from developing the agreed-upon acre. According to the work’s label, found in the exhibition booklet, ‘The plot will remain unmarked. It will degrade the value of the institution’s property’. This stark statement raised questions. Artist Aria Dean pointed out in a review of the show for 4Columns: ‘Is the land’s value not more likely to appreciate’ – thanks to its new designation as a conceptual artwork – ‘in the same way that a house previously owned by a celebrity would?’

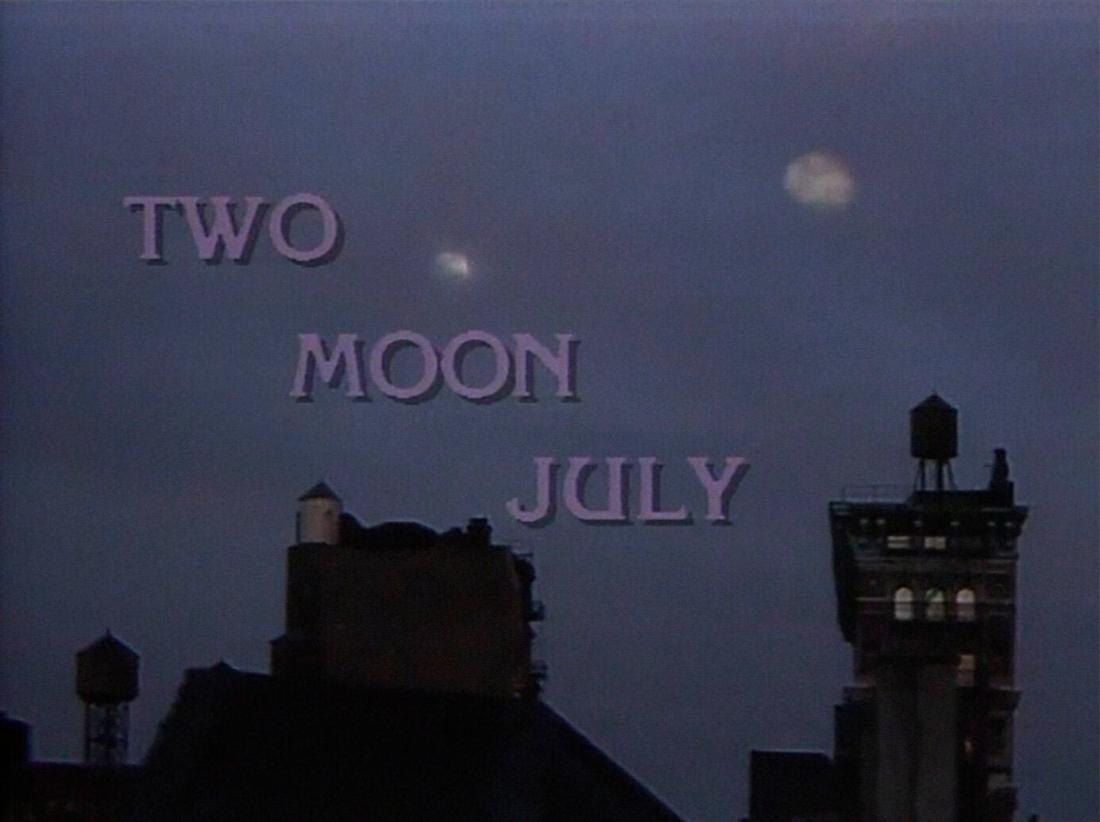

The ambiguity of this agreement between the artist and institution was still bothering me a week later when I watched Wong’s Made for Telefishion (2024), a 44-minute variety show-style video in Lines of Distribution, an exhibition of artworks co-commissioned by The Kitchen, the Lofoten International Art Festival and the North Norwegian Art Centre. The video, made from research conducted in the archives at each of the institutions, looped in a large custom-built viewing room at the centre of the The Kitchen’s gallery (other commissioned works included a poster and a performance during the show’s opening weekend). Actors played the parts of a Norwegian fisherman, his wife and their two young-adult daughters, who learn that the fisherman has been recruited by the Norwegian government to conduct “maritime intelligence activities”. As the family reacts to the news, their TV turns on by itself, displaying a misty periwinkle title card that reads Two Moon July. They are confused until one of the daughters pulls out her phone and explains, “Two Moon July was an experimental television program produced by The Kitchen art center in New York in 1986”; indeed, Wong’s viewing room was flanked by two panels displaying funding applications and promotional materials related to Two Moon July.

Later, the fisherman declares, “I’ve been doing some research”, and describes how The Kitchen brought “a bunch of American experimental artists to countries in Europe” during the 1980s, on a tour sponsored by the US government’s International Communication Agency, which “had a clear geopolitical agenda”. Despite this, he says, “The Kitchen found itself free to ignore this agenda and use the opportunity to simply promote artists and ideas that they found worth promoting”. Feeling “inspired” by his research, the fisherman decides to embrace his own creative freedom “while officially embarking on the mission assigned [him] by the government”. “They’ve given me access to all sorts of resources”, he says. “I’m convinced I can put it all to far greater use”. At this point, it would be easy to interpret his lines as a proxy for the artist’s own intentions with the project – a reflection both on the historic scope of institutional critique as well as its limitations. Yet as a conceptual tradition, it does not adequately characterise Made for Telefishion.

While it’s a tried and true tactic to appropriate an institution’s resources for ‘greater’ purposes (just as Rowland attempted to devalue Dia’s land as part of a sanctioned exhibition), Wong seemed to be doing the opposite. Her exhibition presented an aesthetic culmination of self-study that propagated an institutional agenda with a wink and a nod. While Plot took a nominally agonistic approach, Made for Telefishion’s congeniality towards The Kitchen hinted at a stranger phenomenon: the merging of the research-based artist with the artist-as-curator (à la Fred Wilson), into what might be called the artist-as-curator-of-institutional-history. This figure promotes the institution rather than being promoted by it, repackaging institutional identities rather than reorganising its collections. While Rowland seemed intent on performing institutional critique as it was practised by Asher, Wilson and others before, Made for Telefishion gave a glimpse of how artists and institutions may have implicitly decided, after decades of negotiations, to move forward together as co-authors.