The state of art criticism today resembles a crisis of freedom, where one reality has been rejected but another has yet to be conceived

On a drizzly Wednesday evening in August, I joined a queue in front of KGB Bar in the East Village to attend a talk by the cultural theorist and University of California Irvine professor Catherine Liu. The programme, titled ‘Gangster Capitalism, Big Bosses, and New Turf Wars in the Class Struggle’, arose from Liu’s recent work on Hollywood gangster films. Onstage, Liu sat in front of a red curtain and under a disco ball. Across from her was Katherine Krueger of Current Affairs, who asked astute questions about Stagecoach (1939), Goodfellas (1990) and Scarface (both 1932 and 1983 versions), and bantered with Liu for roughly an hour before a rapt audience. America, they agreed, has entered a new and unique phase of capitalism. Employers, colluding with private insurance and surveillance tech companies, are increasingly exercising the power of life and death over workers, while the political and economic crimes of those in the highest offices are not only being committed in the open but celebrated by swathes of the population. Under this jerry-rigged system, Liu argued, workers should embrace and organise around the figure of the gangster.

The crowd was full of artists, musicians, writers, actors, creative directors, graduate students, lawyers and community organisers, though the attendee beside me volunteered that they worked for Capital One, which, they noted, provided great corporate membership benefits at MoMA. In our late-capitalist age of perks and precarity, Liu, a vocal opponent of centre progressive politics, has proven adept at capturing a wide array of hearts and minds and spreading her ideas beyond academia. I first encountered the term ‘gangster capitalism’ on her Substack, where she offers an eponymous course to paid subscribers, with custom-designed merch to boot. At KGB, Liu reiterated many of the points she’s made online: white-collar bosses are mob bosses in disguise; workers toiling for wages are “corner boys for the capitalist”; what once may have been called the criminal underworld is now just “reality”. Nothing is glamourised in American society as much as ambition, usurpation and betrayal. Predictably, the discussants delighted in mentioning America’s “gangster capitalist” president, who recently deployed National Guard troops into US cities over the heads of local government officials, imposed sweeping tariffs on goods from nearly every country to force concessions on trade and other issues, and launched a campaign of extortion and blackmail against universities, museums and media companies. “What is really incredible”, Liu said with chagrin, “is you have this gangster in charge, and you know what we’re doing? We’re writing a lot of letters.” Instead of performing shock and outrage “like little prissy New York Times writers” or “gather[ing] 250 signatures from professors”, mistaking a petition for a show of force, workers who want universal healthcare should, in Liu’s words, “grab it out of the hands of private insurance companies”.

Liu’s disparagement of these ‘letter writers’ reminded me of another event that took place at KGB back in March. This one, titled ‘MANIFESTO!’, was a reading hosted by 4Columns where five art writers recited short criticism-related manifestos presaging some of the political, intellectual and financial frustrations that I would later sense in the air at Liu’s talk. It occurred to me that the manifesto, which still carries a strong whiff of twentieth-century European avant-gardism, is another form of letter writing and perhaps one that’s no closer than a call to Congress is to praxis. Johanna Fateman, former New Yorker columnist and current co-chief art critic for CULTURED, pointed out in her reading that the critic nowadays, working in the face of corporate conglomeration and shrinking budgets – in short, under gangster capitalism – is “in the abject position of providing a kind of intellectual decoration, itself threaded through with advertising, for the apparatus of shopping and mass surveillance”. “Criticism as a profession”, Fateman said, “is likely already unsalvageable, even if we were to agitate for a number of stopgap or transitional measures” such as “a 300 percent word-rate increase in pay for freelance critics or targeted campaigns against our nemeses at the so-called paper of record and legacy magazines.” The politically aware, anti-capitalist critic thus is in a bind. Ciarán Finlayson, a writer and managing editor of Blank Forms Editions, argued, “Engaged practitioners and critics are desisting from engaging the artworld as their primary site of political activity, and instead joining political organisations and social movements with strategic leverage, an orientation toward labour and the capacity to challenge state power.”

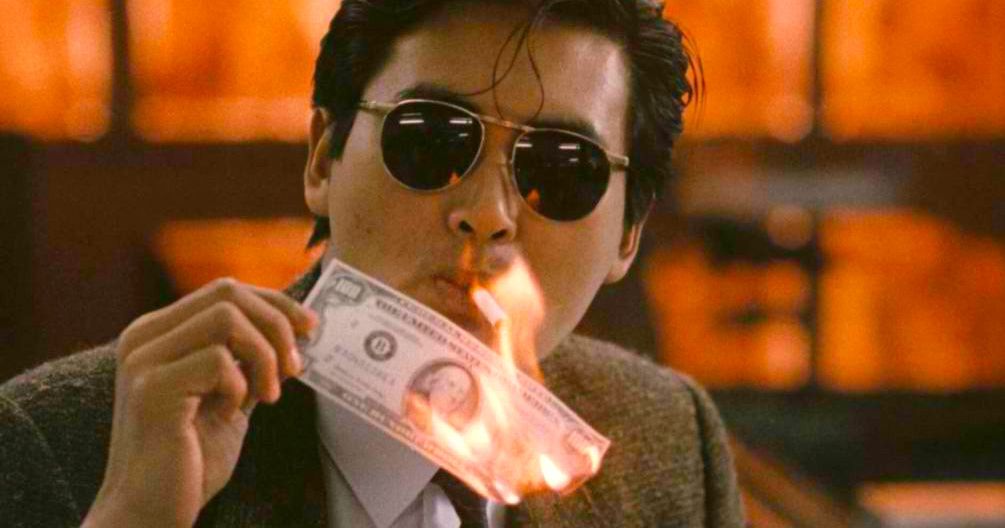

A few days after Liu’s talk, a classic gangster movie, John Woo’s A Better Tomorrow (1986), happened to be screening at the IFC Center in Greenwich Village. In this film, Sung Tse-Ho (Ti Lung), a senior triad member, retires from organised crime when his kid brother joins the Hong Kong police force, but the syndicate, embodied by the boss’s righthand man, Shing Dan (Waise Lee), won’t let him leave without completing one last job. If Ho takes the job, he endangers his brother, who would be tasked with apprehending him; if Ho refuses, he risks subjecting his friends in the triad to Shing’s ire. Although it boasts all the trappings of a Hollywood gangster flick – shootouts, megalomania, burning cash – A Better Tomorrow is highly existential. Despite being coerced, Ho conducts himself as if he were radically free, like the student described in Jean-Paul Sartre’s 1945 lecture ‘Existentialism is a Humanism’, who is torn between fighting in the Second World War to avenge the death of his brother and staying home to care for his mother. Like Sartre’s student, Ho is ‘condemned to be free’ and must invent his own solution to his problem, one that involves a heist, a hostage exchange and a spectacular shootout, during which he kills Shing with the help of his police-officer brother.

Liu might say that the point here is perfectly straightforward: no matter if one is trying to climb the ranks or get out of the game, as a gangster or an average worker in a capitalist society, the answer is to kill the boss. But A Better Tomorrow is a curious case for another reason, in that it’s a study of the crisis of freedom, a study of what happens when one all-encompassing way of life has been rejected but another set of conventions and protocols has yet to be conceived. And that is likely where most art critics stand today: having turned away from ‘unsalvageable’ institutions and mores, we find ourselves radically free – which is to say, rudderless, but also, perhaps, dreaming of the next spectacular revolt.