With their semi-covert political messaging, could Anne Imhof’s DOOM and Alex Tatarsky’s Sad Boys act as a blueprint for future activist art?

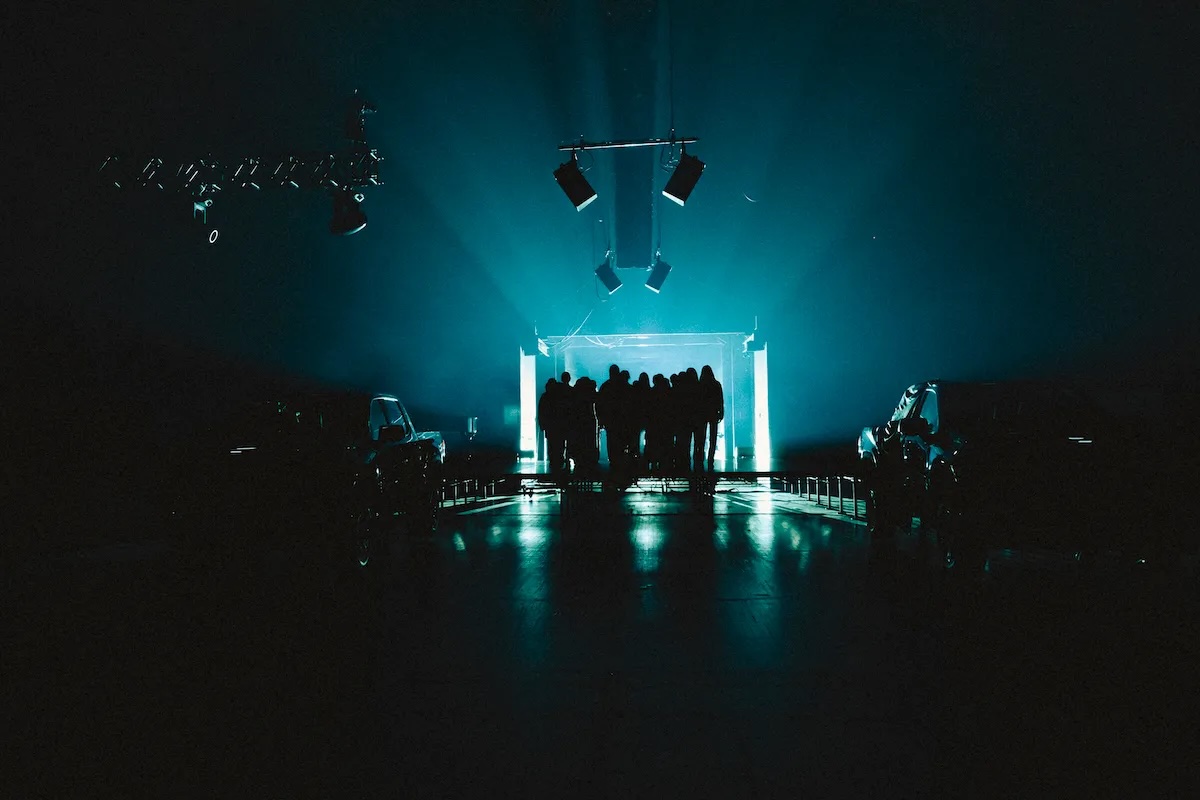

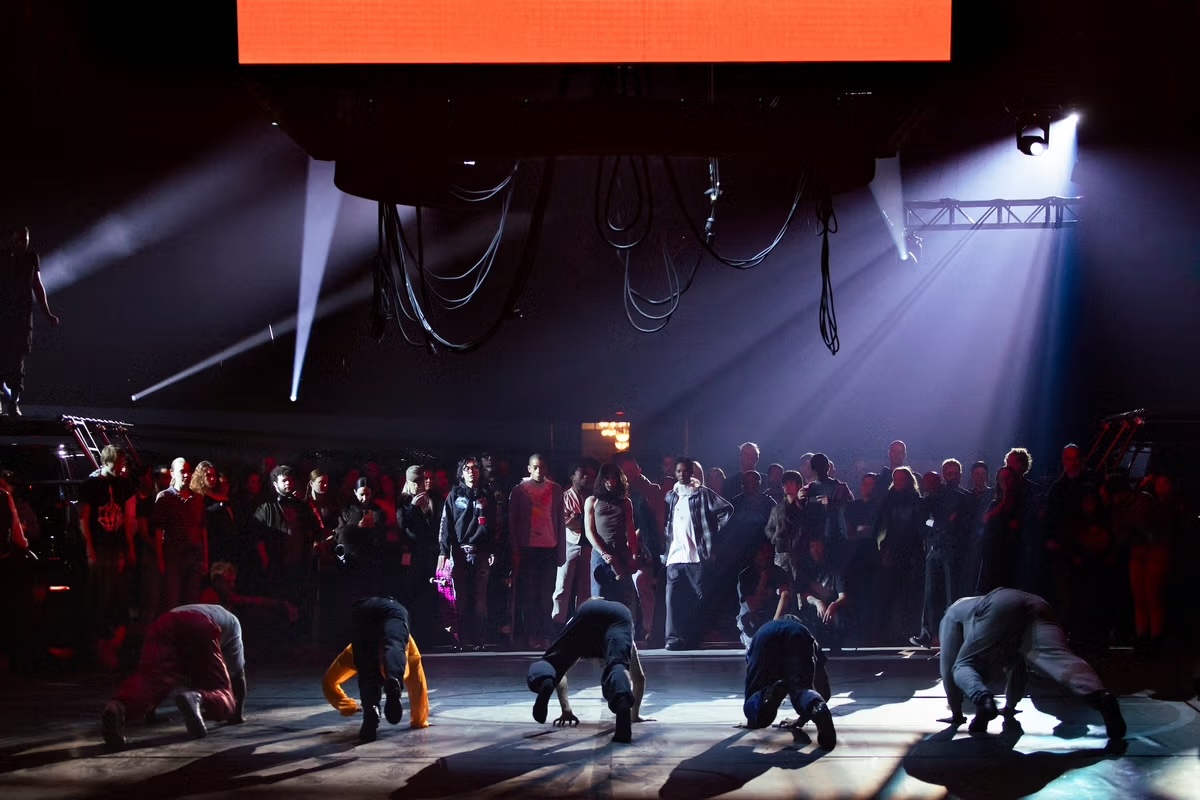

For three hours a night, for over a week in early March, German multidisciplinary artist Anne Imhof made valiant attempts, as part of her latest gesamtkunstwerk, DOOM: House of Hope (2025), to mould the atmosphere of the Park Avenue Armory’s Wade Thompson Drill Hall as her material. She did so by directing a cast of 60 performers – including actors, models, rappers and dancers – in the delivery of a cut up and chronologically reversed Romeo and Juliet (1597), staged in a series of immersive tableaux vivantsthroughout the dim, oversize gymnasium. Perched atop and around 26 shiny black Cadillac Escalades, performers enacted scenes of tragedy and romance. Spectators, kept on their feet for the duration of the show, could wander freely and photograph the modern-day, supposedly high school-aged Capulets and Montagues but never directly interact with them. The effect was that of feeling invisible in a large, cliquish crowd.

There was a consensus among critics that the disaffected youths in DOOM, pointing finger guns at their temples, were commenting on what one writer called ‘the overarching dysfunction of the Western world’, though only through their visuals. Indeed, the costumes designed by Imhof’s longtime collaborator Eliza Douglas – vintage tees, faded denim, cheerleading uniforms and basketball jerseys – were recognised to be, as another reviewer described, ‘American to the max’, but according to articles published the day after DOOM’s premiere, the ‘comically apolitical’ performance gave its US audience ‘no answers’ for dealing with their anxieties about the present. A critic at the Times surmised that Imhof ‘is struggling, a lot, with how to make something meaningful and powerful in 2025’. Those who noticed the smattering of handwritten cardboard signs that appeared on the floor seemingly out of nowhere in the show’s second half, two of which read ‘Trans Rights’ and ‘You Can’t Control My Body!’, clocked them as a weak nod to activism. The signs remained an anomalous element, an unresolved tension, in Imhof’s otherwise homogeneous tableau. They struck me as a site of potential, though I wasn’t sure yet what to make of them.

To try to better understand DOOM, I drove out of New York to see a show in Philadelphia that seemed to promise the opposite of everything found in Imhof’s symbolic behemoth. This performance was titled Sad Boys in Harpy Land (2023), and it was, according to the venue, a ‘sad clown show’ and ‘demented cabaret’. It was the brainchild of Alex Tatarsky, a performance artist and classically trained clown who adroitly embeds social, political and class critique into skits that are deliriously lowbrow and disarmingly comedic. Tatarsky, who cofounded art collective Shanzhai Lyric and its subsidiary group Canal Street Research Association with Ming Lin in 2015, is interested in the profound absurdity of everyday encounters, and has staged live shows including Americana Psychobabble, Dirt Trip, and MATERIAL, their recent improv project at the Whitney Biennial.

Sad Boys, a monologue in which Tatarsky plays multiple personas,opened on a crack of thunder as Tatarsky entered, wearing an oversize grey beard, so as to embody what they described in their monologue as the mythical figure of the Wandering Jew. They took a sip of coffee from a paper cup (many of which were scattered around the set as preparation for later jokes) and choked on the liquid. As a pair of red curtains that made up part of the set fell, Tatarsky was onto their next bit, chewing and spitting tinned fish onto the stage, parodying who they revealed, shrieking with their mouth full, to be Oskar Matzerath’s mother in Günter Grass’s 1959 novel, The Tin Drum. I found the elaborate props and tireless physical humour refreshing, given DOOM’s aloofness. There were, however, uncanny similarities between the pieces, namely the motif of disintegration and a spiralling death-drive. Several times, Tatarsky screamed, “My mind is a hellscape” and “I want to die!” and once, enacting the frustrated playwright Wilhelm Meister in Goethe’s eponymous bildungsroman, pretended to hang themselves with a silver cord. Instead of feeling confused and put off in these moments, as many were by the juvenile finger guns in DOOM, Tatarsky’s audience burst into laughter.

Unlike Imhof’s performers, who were busy affecting what one article called a ‘fictional coolness’, an aloofness meant for social media, Tatarsky constantly threw eye-contact, pauses and other cues at their audience, inviting us to laugh. Through laughter, a feeling of collectivity germinated, one that Tatarsky was able to then shape and intensify, as Imhof seemed to want to do from the moody outset of DOOM. Towards the end of Sad Boys, Tatarsky instructed us to stand and walk down to the stage – through the putrid piles of anchovies and other detritus – into the theatre’s green room. There, Tatarsky pressed two halves of a raw onion into their eyes, making tears stream down their reddened face. Then, reinhabiting their Wandering Jew persona, they picked up a guitar and brought the performance to a close by singing softly about their desire for neither a ‘country’ nor a ‘military’, implicitly critiquing the Israeli occupation of Palestine. There was a distinct shift in emotional register here that had also accompanied the mysterious appearance of DOOM’s cardboard signs. It was precisely due to the raucous absurdity of what preceded Tatarsky’s key-change that their song felt all the more sober and sincere, just as the aloofness that characterised most of DOOM threw the immediacy of the words on those scattered signs into stark relief.

If Sad Boys was able to act as vehicle for a political volta, I wondered if DOOM’s veneer of coolness had also served as a kind of surface on which a message about trans rights and bodily autonomy was rather covertly embedded. Could the formal tactic of having a tiny sliver of a gesamtkunstwerk deliver an important message serve as a blueprint for future activist art? It’s become, in the US under the second Trump administration and worldwide in the face of surveillance and censorship, increasingly necessary to find new ways for culture to participate in activism. While we will continue to need artworks that fundamentally function as activism – such as the shipboard gynaecological clinic operated by Women on Waves, a Dutch NGO that provides reproductive health services in international waters, whose maritime ‘installation’ was funded by a visual arts grant – it may be necessary not to rule out other forms of art, whether heartfelt clowning or moody immersive theatre, as potential vessels for semi-covert communication.