From the rise of ‘red-chip’ artists to exhibitions of underground comics, the values of the traditional artworld are being challenged and reshaped

In early April, I caught the tail end of Doki Doki Tutu’s Delivery Service!! at Tutu Gallery, an apartment gallery in Bed-Stuy. The work that drew me into the two-person show was Brooklyn-based artist Amos Kang’s 3D-printed sculpture Bella Boo (2024), a cockroach the size of a small dog with the head of a cartoon girl, dark brown hair and red irises. Like an NFT that crawled out of the screen, Bella Boo is an oneiric amalgamation, the kind that might appear if one types ‘Gregor Samsa’ and ‘anime’ into an image generator. Mounted high on a wall, belly exposed, legs curled inward, antennae droopy, she looks nearly dead. Images of the sculpture online don’t invite slow looking as much as protracted gawking, but in-person Bella Boo is rather cute. Kang seemed to be approaching the same concept as Louis Osmosis’s papier-mâché roach on a leash, Companion (Hachikō) (2022), from another, slightly more cursed, angle.

Importantly, Bella Boo looked less like a self-contained expression of an idea or emotion than an obscure trademark character. That Bella was in fact a character for Kang was confirmed in another of his sculptures, A letter to our daughter- Your mother and I don’t yet have the words to describe the hope you give us for the future. -Mark Zuckerberg- (2024), a diorama composed of a plywood house festooned with knickknacks – a doll’s house balcony, a heart-shaped lock, a Studio Ghibli-style family portrait – built on a block of soil. On the side of this dirt-covered plinth is a 3D-printed potato labelled with Bella’s name. Bella’s potato forms a node in a root system containing around 20 names (Vicky, Dale, Soo Min…) that can be read as a family tree – albeit for an asexual species, since the offspring here appear to issue from single parents – or a diagram of influence, like those generated when scholars apply network analysis to art history. The wide-faced, cartoonlike children that appeared nearby in Yizhi Liu’s acrylic paintings also seemed to be characters from a peculiar pictorial universe. The largest of Liu’s paintings in the show, ( °Д)( °)( )(°; )( Д° 😉 (2025), depicts a group of five Yoshitomo Nara-esque beings gathered around a sod-covered table, cutlery in hand, waiting for a meal to be served.

At Tutu Gallery, I recalled Annie Armstrong’s recent article ‘Forget Blue-Chip Art. It’s a “Red-Chip” Art World Now’, in which the Artnet columnist identifies a new constituency of artists and collections, whom she calls ‘red-chippers’ (to distinguish them from the traditional ‘blue-chip’ set). This group includes, on the creator side, artists like Beeple, KAWS and MSCHF, with their trademark styles and characters and products offered at every price point, and, on the collector side, digital natives less concerned with art history than with entertainment, NFTs and ‘artworks that look like toys’. It occurred to me that Kang and Liu’s cartoonish and seemingly born-digital aesthetics may appeal to and feel accessible to someone whose interests lie outside the traditional artworld – and that part of what felt urgent in Armstrong’s article was the idea that new values were coming in to challenge those that dominate the traditional artworld (what red-chip values are is another conversation).

I was able to dwell more on the broader implications of Armstrong’s article, which have to do with the nebulous inside-outside dynamics of the traditional artworld, at the show New Comic Day at Subtitled NYC, a project space in Greenpoint. Displayed on the walls here were comics on paper, cardboard and canvas by ten contributors, whom Jaejoon Jang, who runs the space, characterised as ‘underground and outsider artists’. Indeed, the frenetic psychedelia and lumpy-faced forest creatures found in Mikael Choukroun’s screenprint Pagina uno de me libro para el uniqo dios y mi familia (2025) and accompanying ink-on-paper works were reminiscent of the images of outsider artist Paul Shimon. Takashi Nemoto’s acrylic painting Art Art Art (2022) presented a pornographic tableau so brazen that one might only have shared it online under a fake account. In two pencil-on-paper works by Anke Feuchtenberger, both titled Kuckuck (both 2021), bald, childlike figures with bare torsos wearing big, ballooning skirts appear to be finger-painting with black ink on the nose and chest of an adult with stubbly facial hair. They reminded me of Henry Darger’s Vivian Girls, imaginary characters to whom the reclusive self-taught artist devoted around 300 watercolour illustrations and a 15,000-page novel.

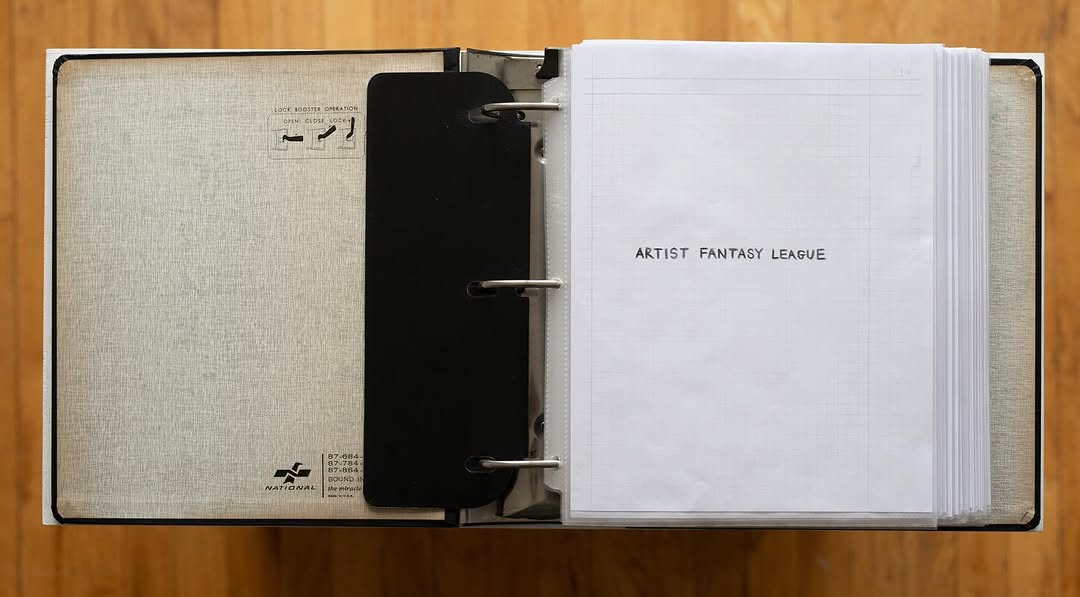

The fact that Darger’s Vivian Girls illustrations were acquired after he died in 1973 by major museums such as MoMA – which, by the way, also collects comics – reinforces the adage that, over time, the blue-chip artworld tends to warm to and eventually absorb objects and gestures on its fringes. Beeple, for instance, who, as Armstrong notes, put red-chip art on the map in 2021 when he auctioned an NFT of his collected digital drawings for $69 million, opened his first institutional survey at the Deji Art Museum in Nanjing last November. Some, like the Brooklyn-based artist Liam Murray, have made this movement from the ‘outside’ to the ‘inside’ of the traditional artworld the subject and material of their work. Towards the end of April, I saw Murray’s latest endeavour, Artist Fantasy League (2025), in a two-person show at Pop Gun, an apartment gallery in South Slope. Here, surrounded by six paintings by the Bay Area artist Gary Katiya, all depicting the logo of the Oakland Raiders football team, were 100 photocopied pages of Murray’s handwritten notes arranged in an austere black binder, a reference to Mel Bochner’s canonical Conceptual work Working Drawings and Other Visible Things on Paper Not Necessarily Meant to be Viewed as Art (1966).

To make Artist Fantasy League, Murray checked in weekly, starting in March, with a coterie of 40 self-described ‘emerging artists’ regarding their recent artworld accomplishments. They then wrote down these accomplishments and administered ‘fantasy points’ to all the artists in the ‘league’, who were divided into eight competing teams. Selling a work earned an artist 3–7 points, depending on how much it sold for. Being in a show earned 6–14 points, depending on whether it was a group show, a duo show or a solo show. Press was worth 3–7 points, depending on the prestige of the publication. Other categories included grants, awards, residencies and artist talks. ‘Bonus: Artist Dies’, Murray wrote on one page. Each team got to choose one blue-chip artist as well (Banksy, Basquiat, Hockney, Kusama, Magritte…). The winning team had Hockney as their blue-chipper.

The metrics that give shape to the traditional artworld are spelled out bluntly in Artist Fantasy League, which looked, despite or because of its cynical premise, hellishly fun. It’s too soon to coin another term to describe the next generation or movement that will arise to challenge today’s red-chippers, but suffice it to say that artists like Beeple and KAWS are not the renegades we’ll be reckoning with in the coming years. Emerging and ‘outsider’ artists, hyperaware of the unsavoury mechanisms of the blue-chip artworld, are finding ways to fly in its orbit while pursuing their interests, indexing the conditions of their labour and even here and there providing meaningful alternatives to the latest trends.