Curator Gunnar B. Kvaran’s stated goal for his iteration of the Lyon Biennale was to make a show that surveyed forms of narrative in contemporary practice. It is bitterly ironic therefore that the exhibition wholly lacked a cohesive one of its own. In short, the biennale was curatorially, formally, a mess.

One example from many possible: in the final furlong of the show is a film installation by Czech artist Václav Magid titled From the Aesthetic Education Secret Files (2013). Two projections show clips from what the wall text explains to be a 1970s Soviet drama series, Seventeen Moments of Spring. The viewing room is laid with a plush grey carpet, with the digits 1, 2 and 3 visible in black in the weave. It’s a quietly dense piece, meditating on the aesthetics of politics; the accompanying text makes reference to eighteenth-century philosophy, contemporary theorist Boris Groys and the poetry of Friedrich Hölderlin. A work that will, with time and thought, deliver rewards. Yet it is encountered straight after a brain-frazzling, epileptic, gurn-fest gallery of Ryan Trecartin’s films, works which purposely (and brilliantly) destroy one’s attention span. It belittles Trecartin. It is disastrous for Magid.

A growing sense of fatigue while moving through the show, catalysed by such curatorial clangers, reaches lethal levels on the ground floor of La Sucrière

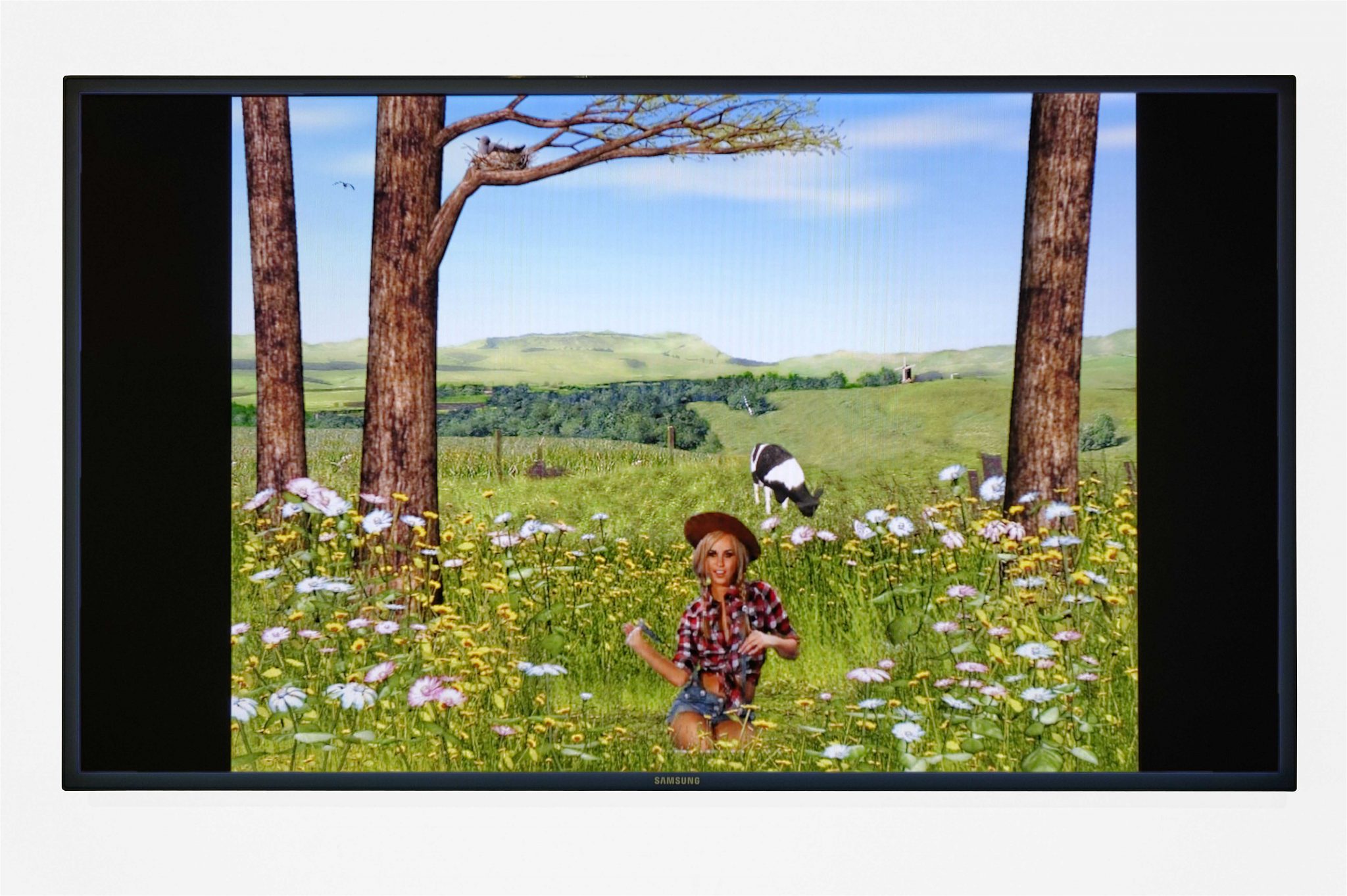

A growing sense of fatigue while moving through the show, catalysed by such curatorial clangers, reaches lethal levels on the ground floor of La Sucrière, the biennale’s regular venue alongside Lyon’s Musée d’Art Contemporain, which, with few exceptions, is given over to works with a digital or animated aesthetic. These ‘range’ from the out-and-out gif-happy post-Internetism of Petra Cortright, whose videos feature the kind of young ladies who might pop up on the web to entice you into a ’cam party, writhing enticingly over digitally rendered (found, perhaps) scenes of pastoral myth, to Dan Colen’s Pop art sculptures of the Kool-Aid Man, Roger Rabbit and Wile E. Coyote, the presence of the latter taking over the venue in the additional form of a cutout silhouette in all the dividing walls, the length of the gallery, as if the toon had rampaged through the place in an effort to escape the work (an understandable reaction: perhaps Coyote was overcame with existential worry as he realised his presence was just dull, irony-laboured posturing by Colen). To the new Net art camp one can add Tabor Robak’s quadrant of digital renderings depicting a Victorian domestic interior, an Asian supermarket, delicate fine cuisine and CCTV-like animation of magnified bacteria.

Elsewhere, Ed Fornieles’s wholesale shipment of his recent pop culture-filled Los Angeles exhibition, Despicable Me 2 (2013), felt too aesthetically similar to Bjarne Melgaard’s work Untitled (2013). In the former, a large cardboard cutout cock vied with sculptural renditions of Family Guy’s Stewie Griffin and other zinging Generation-Y motifs. This visually cacophonous ‘stuff ’-piled-‘messily’-in-a-room vibe is also utilised by Melgaard, with a gallery filled with old sportswear, stop-frame animations and a sculptural Pink Panther taking a woman from behind. The viewer, in the end, becomes desensitised to this lowbrow burlesquing. I don’t think it’s necessarily the artists’ fault – those mentioned are chasing different ideas, perhaps – but something has to be wrong when you’re staring at a cartoon character’s grossly engorged pink-sequined penis with an air of total ambivalence.

The viewer gets minor, but much needed relief from this otherwise all-pervasive sense of hipsterish detachment from tangible reality with Laida Lertxundi’s excellent film collage The Room Called Heaven (2012), which, with its shots of a hand swirling an ice bucket or a woman standing near a clanging railway-crossing bell, has a welcome sense of physicality to it. Ditto Ed Atkins’s new video, Even Pricks (2013), which, while using digital rendering (animated from motion-capture technology), combines it with a deeply affecting, beautifully written and voiced narrative on depression, adding depth and charge, and a feeling that something is at stake in the work. This is sadly missing from many of the other works in the biennale, and the direction of the show as a whole, which felt merely reflective and muddled: a tale with no point to it, a tale badly told.

This article was first published in the November 2013 issue of ArtReview Asia and the December 2013 issue of ArtReview.