Outliers and American Vanguard Art, LACMA, Los Angeles, 18 November – 17 March

Once upon a time there was mainstream art and ‘outsider’ art, two wholly separate worlds. But Outliers and American Vanguard Art – the fruit of years of research on the part of Lynne Cooke, curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, where this show originated – tells another story. Limiting its scope to the US and substituting ‘outsider’ for one of Malcolm Gladwell’s buzzwords, Outliers… uses some 250 works by 80 artists to evidence how avant-gardists were consciously informed by self-taught figures like Morton Bartlett, James Castle, Greer Lankton et al. It’s structured in three parts: looking first at early American Modernism, the show segues into the 1960s interplay of eccentric outliers and cadres such as the Chicago Imagists and West Coast assemblage artists, and plays out with ‘the continued impact of outlier practices on contemporary art’. Included, alongside the above-mentioned, are stars of the margin such as Martín Ramírez, Henry Darger and Lonnie Holley (interviewed elsewhere in this issue), and artworld luminaries including Kara Walker, Cindy Sherman and Matt Mullican.

Rochelle Feinstein, Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York, through 3 March

Rochelle Feinstein was herself an outlier of sorts for much of the last four decades, despite spending a quarter-century teaching painting and printmaking at Yale. Over the last few years, though, her richly flexible art and influence on younger painters has been recognised, and she’s enjoyed a touring retrospective in Europe. Now it’s her home country’s turn to wave the palm fronds. Feinstein is predominantly an abstractionist, but her art is the inverse of hermetic or formally purist. It often incorporates photographs and overspills of scrawled language – reflecting the ubiquity of textual communication in everyday life – and often touches on the real world more widely. The series A Catalog of The Estate of Rochelle F. – Paintings 2009–2010 (2010), a faux-posthumous estate tabulated through raw, text-splattered black-and-white collages, seems to anatomise the artist’s effects in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis; a radiant, rainbow-hued, gauzy abstract from 2012–13 is titled In Anticipation of Women’s History Month. A 1990–97 series, The Wonderfuls, deliberately overuses the word ‘wonderful’ until it empties out (Wonderful Sex, Wonderful Vacation, etc), yet it’s an epithet frequently applicable to her work.

Taipei Biennial, Taipei Fine Arts Museum, 17 November – 10 March

Taking a hard left from wonderfulness, a UN report on climate change (just published at the time of writing) is arguing that there is a dire need to reduce carbon emissions by 45 percent should we not wish the planet to become a living hell by 2040. Governments are shrugging their shoulders; the US is adopting an ‘it’s too late, so let’s do nothing’ approach. So it is not inappropriate or untimely that the 11th Taipei Biennial – curated by Mali Wu and Francesco Manacorda, held at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum and subtitled Post-Nature – A Museum as an Ecosystem – is styling itself as ‘a platform for multi-disciplinary discussions of ecology’, and aims to ‘shed light on environmental issues through international artists’ perspectives’. For exhibition spaces, read ‘eco-labs’ that will change as the show goes on, the exhibition as a constantly morphing ecosystem of its own. In terms of participants – 41 of them, from 19 countries – artists will mingle with NGOs, activists, filmmakers and more, and include Julian Charrière, Ursula Biemann, Hsiao Sheng-Chien, Jumana Manna, Kuroshio Ocean Education Foundation and the Thousand Miles Trail Association. And, presumably, nobody is arriving by plane. (A carbon-neutral biennale, there’s a proposal.)

Felipe Baeza, Maureen Paley, London, 17 November – 6 January

In recent works by the US-based Mexican painter Felipe Baeza – a 2018 Yale graduate whose degree show impressed Maureen Paley enough that she’s now representing him – treelike forms sprout from the mouths of figures who themselves appear emerging from black waves or perhaps soil, or lie prone on their backs, choked or supported (again, it’s not entirely clear) by midnight-blue figures. If there’s a lot of equivocating in that sentence, it’s because so much in Baeza’s art is pointedly between: not even entirely painting, factoring in as it does printmaking and collage elements including twine, cut paper and glitter. For the artist, who draws on his own experiences as well as techno outsiders Drexciya’s Afrofuturist mythmaking, these are depictions of what he calls a ‘migrant fugitive body’, both dislocated from home and queer. The body here is fragmented on both formal and metaphorical levels, and the paintings tend to be set at night, ‘where transformation happens’. If there is an agonistic aspect to Baeza’s work, then, it’s counterbalanced by a hopefulness concerning moving past rigid identities. The paintings have the graphic velocity of, say, Leon Golub, with a dash of Francesco Clemente’s skewed dreaminess, but their hopefulness about art’s emancipatory potentials is Baeza’s own. One to watch.

Tris Vonna-Michell, Jan Mot, Brussels, through 1 December

Tris Vonna-Michell has also, since the middle of the last decade, drawn on his own life story, if slantwise. His blend of slide projection, film, rapid-fire lecture-performance performed to an egg-timer, and photographic stills has functioned as an extended, ever-augmenting quest for the understanding of his own biography, involving shaggy-dog-like stories in which Vonna-Michell tries to track down crucial (to him) bits of information. His career has been a weird one thus far because he’s generally stuck to this storyline. Early on, he was fascinated by Henri Chopin and the late concrete poet’s connection to his own family (Vonna-Michell asked his father why he, Tris, was born in Essex; his father told him to find Chopin). And it appears he still is, given that a recent film is titled Chopin (2018) and will likely appear in his new show, Walking Sonic Texts – Sound Poetry and Movement in Space. Such is the obsessive impetus underlining Vonna-Michell’s art, though, that it’s hard to see how he could have operated any other way.

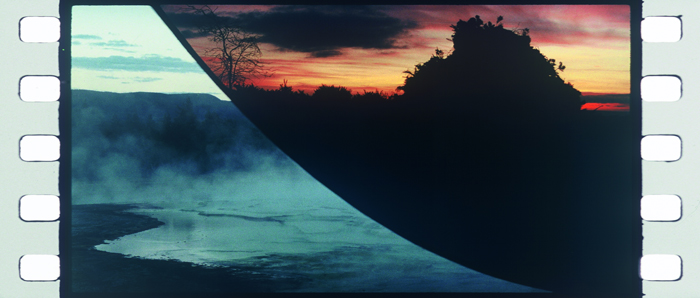

Tacita Dean, Kunsthaus Bregenz, through 6 January

The art of Tacita Dean was an act of compound preservation long before she began campaigning, in 2011, for the perpetuation of photochemical film. From her chalk drawings to her sumptuous, elegiac films, her art has concerned itself with what time washes away, and what might conceivably stay. At Bregenz, that’s summarised by three films: the six-part Merce Cunningham Performs STILLNESS… (2008), the since-deceased choreographer’s willed immobility to a ‘soundtrack’ of John Cage’s 4’ 33” (1952); Dean’s 2011 Turbine Hall commission FILM, all silence, sprocket-holes and scratches as a welter of discontinuous analogue imagery sweeps by; and her recent, long-gestating, hourlong odyssey Antigone (2018), with its mix of Anne Carson poetry, American and English landscape, and bearded actor Stephen Dillane as Oedipus. Two monumental chalkboard drawings, The Montafon Letter (2017) and Chalk Fall (2018), round out the show, respectively depicting a mountain landscape and chalk cliff – the latter, inevitably, collapsing.

Maria Eichhorn, Migros Museum, Zürich, 20 November – 3 February

Two years ago, for an exhibition at the Chisenhale Gallery in London, and following a site visit and discussion with the gallery workers the previous year, Maria Eichhorn elected to ‘exhibit’ the closure of the gallery for five weeks. Back in 2002, for Documenta 11, she set up a public limited company whose sole shareholder was the company itself, and for which the capital invested couldn’t increase in value; the same year, she spent her exhibition budget for a show at the Kunsthalle Bern on (apparently much-needed) repairs to the building itself. The reductive but potent gesture is her specialty, and accordingly at the Migros, for a survey of her work over 30 years, she’s chosen only 12 works, including 72 Pictures (1992–93), 72 monochrome panels painted by 43 people during a show in Paris: anyone could sign up and paint, the museum turned into both studio and social space. If there doesn’t end up being much to look at, the content – as with a closed gallery whose workers have withdrawn their labour – is the invisible, but very real, people without which it couldn’t exist.

Gabriel Lester, Fons Welters, Amsterdam, 23 November – 12 January

Gabriel Lester has been a graffiti artist, MC, director and writer as well as a longstanding artist of note (this is the Amsterdam-based Lester’s seventh show at Fons Welters). Plus since 2013 he’s co-run a design studio, PolyLester. What’s been consistent for some time is the desire to create environments – a sort of expanded cinema – where narratives can arise. This show, Shake a Face, engages with tropism, or the notion that lifeforms and attitudes are moulded by environments. According to Lester – contacted mid-preparation – it will ‘continue my ongoing research into suggested realities and unresolved narratives… an exhibition in flux to flex the mind’. Among those fluxing elements will be a series of petrified plants, slumped but apparently growing again in the direction of a light source; prints of faces whose profiles are made from fine chains that move in response to loudspeakers; and large sculptures featuring a face on one side and geometry on the other, as if a crystallisation of thought. A recent one of these was called Bambaataa (2018); for Lester, evidently, the hip hop don’t stop.

Martin Beck, 47 Canal, New York, November – December

Club culture also infuses Martin Beck’s Last Night (2016), a 13-hour video in which each of the 118 songs played by David Mancuso at the last night of the long-running New York dance party The Loft is replayed in sequence on a domestic turntable, a tender durational tribute to a long-ago mini-utopia. The Vienna- and New York-based Beck’s work, though, can make that timescale look short. Recent works here include rocks whose clasts have refused to cohere over millennia, though they sit together, remaining big pebbly clusters – a clue that, as in the Loft parties that temporarily brought together different communities, Beck is interested in temporary social unities. And indeed, his diverse shows themselves – stylistically polyglot – enact something similar on the formal level, with this one also including a video based on a Canova marble sculpture; and a group of 24 text drawings. Since, in recent years, Beck has apparently occupied his time by producing one US letter-size ‘document’ per day– saying, in a recent interview, that he finds writing a ‘painfully slow process’ – we doubt he knocked these out in a morning.

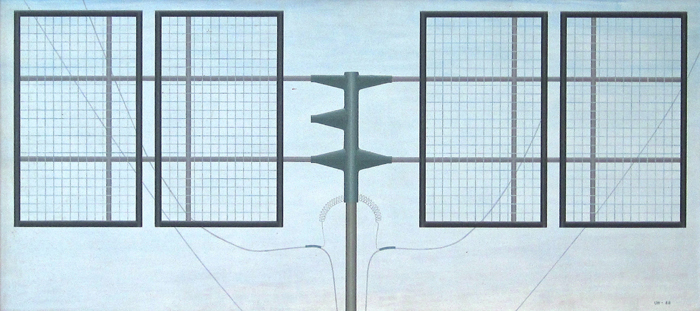

On Circulation, Bergen Kunsthall, 16 November – 13 January

Circulation is probably the key metaphor underpinning contemporary art of the last decade or two: think networked painting and indeed all art that reflects the rhizomatic model of the Internet; think too of how our world is defined by, as Bergen Kunsthall puts it in describing their 12-artist group show On Circulation, ‘flows of capital, networks of people and information that connect distant parts of the world and various levels of social productivity’. The curating is gratifyingly off-beam (eg no Seth Price, no Michael Krebber), the work on show stretching from Swedish painter Ulla Wiggen’s luscious realist 1960s images of circuit boards to Nina Canell’s works involving dinky microchips and sliced cucumbers, to Park MacArthur following the progress of a piece of marble from a Norwegian quarry to an American museum. The show itself, the organisers note, is a ‘network’ of approaches, rather than a single-pointed thesis, which is fair enough since maybe a viewer doesn’t need to be told what circulation means in 2018. To quote some old Palmolive commercials, “you’re soaking in it”.

From the November 2018 issue of ArtReview