NUSA, an exhibition to mark the reopening of Malaysia’s National Art Gallery, seeks to plot the history of Malaysia’s modern art – but seems to undermine itself at each turn

Malaysia’s National Art Gallery (Balai Seni Negara, colloquially shortened to Balai) has reopened, following two years of renovations, with NUSA, an exhibition of its permanent collection. Nusa, Sanskrit for ‘homeland’, and its derivative Javanese word Nusantara, are often used as shorthand for the Malay Archipelago. With over 400 artworks on display, the exhibition attempts to plot the history of Malaysia’s modern art and its regional connections from the twentieth century to the present. According to the wall text, this is a way of ‘highlighting the validity, the interpretation, and the fiction, as well as tracing the essence of social and cultural structures that form the tapestry of the region’. Taking a non-chronological approach, the show succeeds in subverting the usual linear narratives of modern art’s ‘progression’ to contemporary art. But it is an ultimately feeble attempt to tell a regional history, due in part to some bewildering curatorial choices and – more perniciously – lightly veiled regurgitations of state propaganda.

The show is divided into eight themes (among them ‘Solicitude Culture’ and ‘Sowing Inner Characteristic’) and two media (‘New Media Art’ and ‘Works on Paper’), creating a total of ten sections. Refreshingly, NUSA includes indigenous carving practices within the story of modern art in Malaysia. Tradition and modernity are conceived not as opposing poles but entangled realities. In the New Media Art gallery, masks from the indigenous Mah Meri tribe dating from the 1950s to 1970s are placed alongside When you are not your body… Life, death and in-between (2008), a multimedia installation by Lim Kok Yoong. Though drawing on radically dissimilar epistemologies, both sets of works explore the body’s afterlife: while Lim’s work considers the body of information we leave online, Mah Meri masks represent the spirits of ancestors and are used in ceremonial worship. Elsewhere, however, arguments become less focused. How a work of graffiti representing an engine by SnakeTwo, statues by indigenous Orang Ulu groups and a prayer mat made of nails by Shahrul Jamili Miskon relate to each other seems more like free association than considered selection.

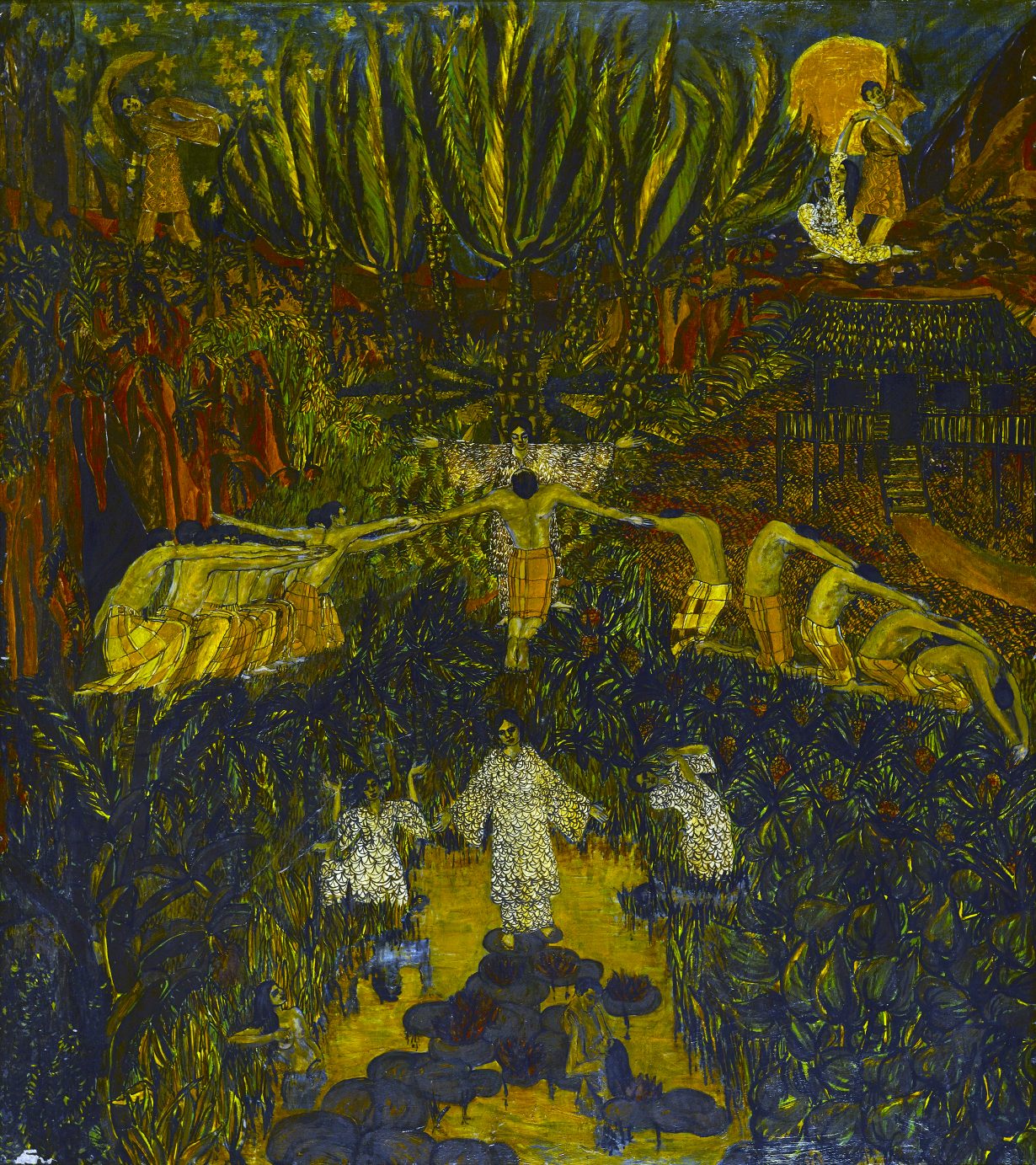

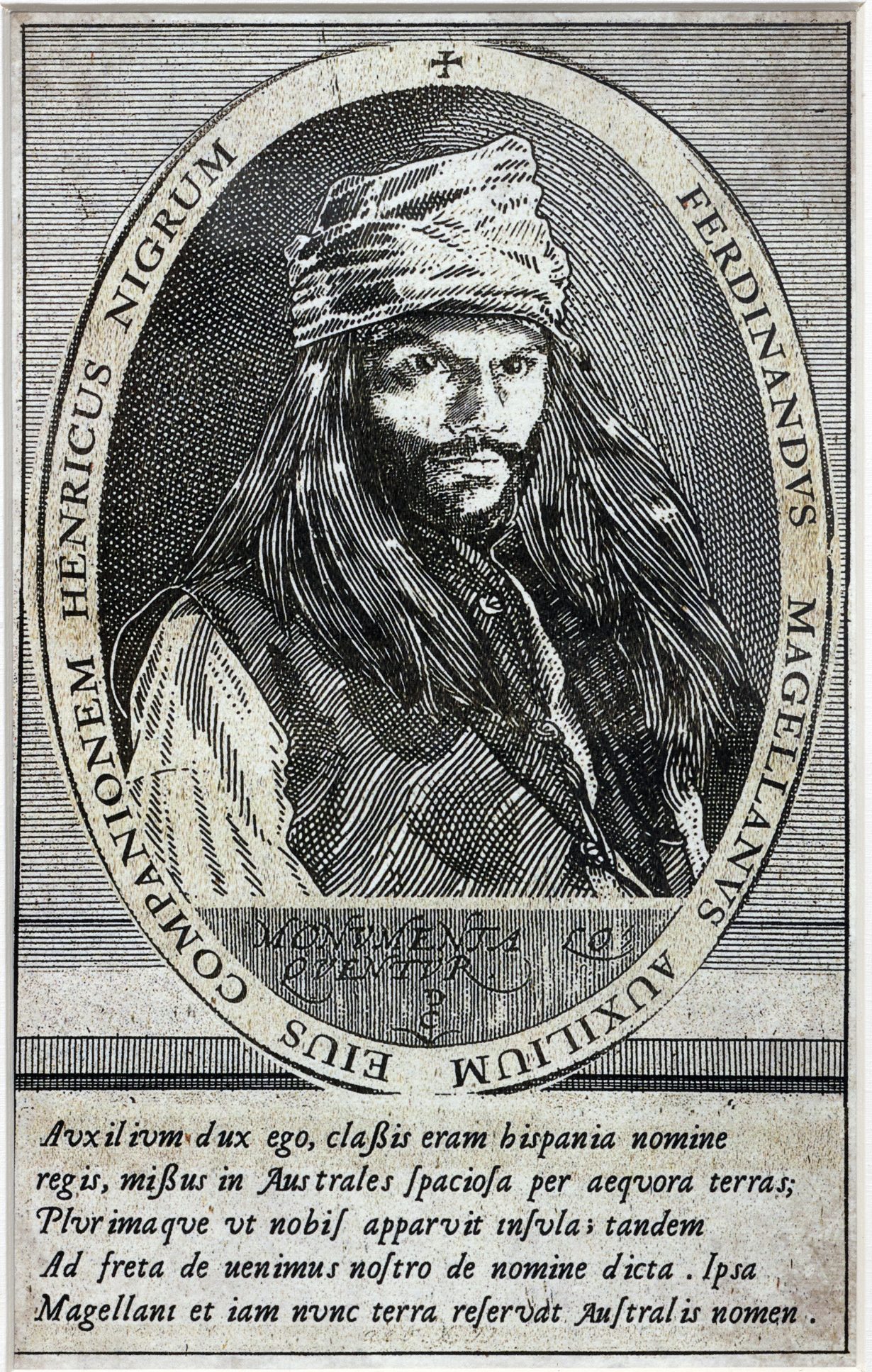

More alarming than the weak curating is its implicit nationalism. While the exhibition includes the works of Southeast Asian artists, such as Thailand’s Thawan Duchanee and Indonesia’s Ristyo Eko Hartanto, it is grounded in a fundamentally simplistic view of history. In a section titled ‘Vibe the Verve, Escalating Geist’ – a perplexing translation of ‘Menyebar Semangat’, literally ‘Expanding Spirit’ – the curators seem to pitch Western art against Southeast Asian art, stating in the wall text that the former ‘changed the meaning of art in the Southeast context to become a craft and later “functional art”, ripping off their craft values’. Yet elsewhere in the text, the Malay world is seemingly exempted from this formulation, heralded for its ‘unique and authentic monuments, artifacts, and cultures’. Not even Ahmad Fuad Osman’s Enrique de Malacca Memorial Project (2016), and its exploration of the veracity of national and colonial histories, could erase one’s distaste. Caught between current curatorial trends towards fluid, networked, regional histories and an imperious, unprogressive state, Balai unfortunately tends toward the latter.

Perhaps the curating needed to pander to certain narratives to secure the underfunded institution’s survival. The reopening of Balai follows extensive repairs to a perpetually leaking roof, yet the institution continues to be plagued by logistical issues: one of the five galleries hosting NUSA remains closed due to problems with temperature and humidity control. As early as 1989, art writer Antares Maitreya was commenting on the situation at Balai, ‘When the walls start tumbling down, who cares what you’ve got hanging on them!’

One could see Roslisham Ismail (Ise)’s installation chronoLOGICAL (2015) as a metaphor for the exhibition. Using animations and videos on small screens, ancient and kitschy artefacts, cartoon drawings and small paintings, Ise tells the story of his family ancestry and the history of the Sultanate of Kelantan, in the northeast of Malaysia. On proud display are the things that are usually concealed, the ‘practical’ tools making sure the artwork can ‘work’: electrical wires, extension cords and screws, nails and pedestals. chronoLOGICAL, like NUSA, reveals the conditions of state exhibition-making in Malaysia and the makeshift infrastructure that holds it all together.

NUSA at National Art Gallery, Kuala Lumpur, through 2025