In partnership with Sharjah Architectural Triennial, ArtReview publishes three new essays exploring sites of environmental struggle and models of social organisation. The essays are authored by participants in the inaugural triennial (9 November 2019 – 8 February 2020) and commissioned as part of the Rights of Future Generations: Conditions programme. The complete set of texts can be accessed on the triennial’s website and will be available as a print book from November.

JUNE 1992, MABO

The Mabo v Queensland (No 2) case, settled on 3 June 1992, recognised native title in Australia for the first time. It is often described as a landmark decision, but it merely admits in legal form what to everyone was already an indisputable fact: that Australia was inhabited before it was colonised, and therefore, that these inhabitants had claim to land.

Mabo is often credited for overturning terra nullius, a Latin phrase that translates as ‘nobody’s land’. Most of us Australians were taught that it formed the legal pretext for British settlement of the Australian continent, but we were taught wrong. Terra nullius begins to frame our account of white settlement about 100 years after the arrival of the first fleet. What Mabo overturned then, was not only a moral and legal fiction, but a historical one too. The continent was not ‘settled’ – it was conquered, and the conquerors knew it.

Most of us Australians were taught that terra nullius formed the legal pretext for British settlement of the Australian continent, but we were taught wrong… The continent was not ‘settled’ – it was conquered, and the conquerors knew it

Like so many of the lies that linger around our history, terra nullius is a fig leaf cast back in time so that it might eventually be taken for a historical truth. One of the most pernicious is that Aboriginal Australians lived in a state of subsistence. According to this image of precolonial indigenous society, life was little more than a harsh, unending struggle to satisfy primordial needs with meagre opportunities. It’s a more pernicious lie because it’s one thing to admit to conquering, another to accept that the conquered are your equals. But precolonial indigenous Australians did not live in a state of subsistence. The ample time allocated to ceremony is but one proof of this.

Moreover, as the work of scholars like Bill Gammage and Bruce Pascoe makes clear, this was no primordial state of nature. The continent was designed. Its ecologies were modified, its rivers were controlled, its fields cultivated, its movements and cycles and rhythms manipulated and harnessed in a grand choreography spanning thousands of communities and language groups, and lasting tens of thousands of years.

How is that for an image of Australia? A vast intergenerational, multi-ethnic design project at the scale of an entire continent. Despite the evidence, white Australia couldn’t recognise it, and still can’t. Eventually though, it too will become an indisputable fact.

Take a recent piece of research on the veracity of oral testimonies in Australia. Researchers have recently recorded 21 Aboriginal stories and myths along the coast of Australia, all of which corroborate historical sea levels. That might seem unremarkable, except that the sea levels being described are between 7,000 and 18,000 years old; that makes these empirically verifiable stories that have been accurately transmitted across 300 to 700 generations.

Think about the kinds of social structures required to secure the integrity of such stories over millennia. Their origin reaches back before the invention of writing, even before the invention of language. Despite the time that has passed, despite every attempt to silence the messages that they carry, despite everything that has happened to this island continent since 1788, those signals are still with us. They can be made out if we are prepared to listen.

In 1993, in the aftermath of the Mabo decision, the Native Title Tribunal was established. The claims process is designed to prioritise negotiation and to encourage parties to take responsibility for resolution of native title proceedings without the need for litigation.

The Native Title Act states explicitly that the crucial function of the Tribunal is to facilitate mediation between Indigenous groups and other parties (eg state governments or private parties). That is, once Indigenous claimants have demonstrated title to the land, the law hopes that the claimants will negotiate agreements with these other parties, whether for compensation or future rights. These are referred to as Indigenous Land Use Agreements. The High Court may hear or review cases where the Tribunal fails to facilitate agreement between the parties. Going to court is time consuming, as it typically takes over a decade to reach a conclusion. And it is costly, in the order of tens of millions of dollars.

The Native Title Act brings radically different moral, legal and ecological orders into contact. Their encounter raises difficult questions about the past, present, and future of relationships between black and white Australia

In 1998, the Liberal government under John Howard passed the Native Title Amendment Act, which significantly modified and limited the original Act. The purpose of the amendment was to protect the interests of the pastoral leaseholders whose lands cover 44 percent of Australia’s landmass. More accurately perhaps, the amendment was designed to pre-empt and limit the ability of Aboriginal Australians to test Native Title claims against pastoral leases in the High Court.

In Australia, the state is the sole source of law (1). That law consists of public, verifiable statements. In the case of property claims, maps surveys and deeds are the privileged kinds of statements for establishing the truth of tenure. Yet another legal order exists, in which the state is not the only source of law; where the law is orally transmitted rather than written, a law that values secrecy and initiation rather than public statements – absent of maps, surveys and title deeds. The Native Title Act brings radically different moral, legal and ecological orders into contact. Their encounter raises difficult questions about the past, present, and future of relationships between black and white Australia.

1993, LAMPU WELL, GREAT SANDY DESERT, WESTERN AUSTRALIA

In 1993, one year after Mabo, a group of communities from the Great Sandy Desert met at Lampu Well, on the Northern end of the Canning Stock Route, to explore making a Native Title Claim. Kimberly Land Council Chairman Kurinjinpyi Ivan McPhee explained to those assembled that under Native Title, the claimants would have to prove:

Our culture, our law, our traditional law

Where we come from and who we are

Where we walked on the land

For the next four years, community members, an anthropologist and the manager of the Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency in Fitzroy Crossing would return to country and try to define the area of the native title claim. The claim area they would eventually seek to establish Native Title over was 83,886 square kilometres, or about twice the size of the Netherlands.

Then they made a most startling decision – to paint the proof of their claim

During this period, the question would remain: how to establish in front of an Australian legal tribunal their culture and law, where they came from and who they were? In other words, what, in the eyes of the Native Title Tribunal, would constitute proof of land tenure going back generation after generation?

Then they made a most startling decision – to paint the proof of their claim. It would be the first, and so far the only time in Australian history, that a painting would be entered as proof of historical land tenure. But first, the artists would have to decide what kind of stories to share with each other.

In the words of the artist Tommy May:

“When I was a kid, if my father and my mother took me to someone else’s country we couldn’t mention the name of that waterhole. We used an indirect language which we call Malkarniny. We couldn’t mention the name of someone else’s country because we come from another place, from different country. That is really the Aboriginal way of respecting copyright. It means that you can’t steal the stories or songs or dances from other places. This law is still valid and it is the same when we paint… We can paint our own story, our own place, but not anyone else’s country.” (2)

The artists also had to make a decision as to what kind of stories and what kind of law to share with the Australian Native Title Tribunal. As May recounts:

“We can’t show white people everything. If you tell everybody, it is like selling your country. You have no law there behind. You can give a little bit, but not too much. Kartiya can take away the stories, the pirlurr (one’s spirit), the power for your country and leave you with nothing.” (3)

After agreeing that they would produce a collective painting, the artists made a second startling decision as to the contents of the painting. They decided to paint something that was common to all four of the claimant communities, they decided to paint water holes, or ‘jila’. Water could make different stories and law commensurate.

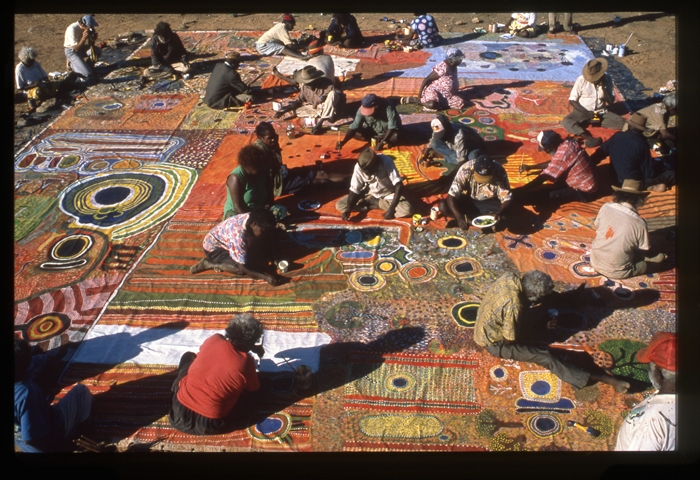

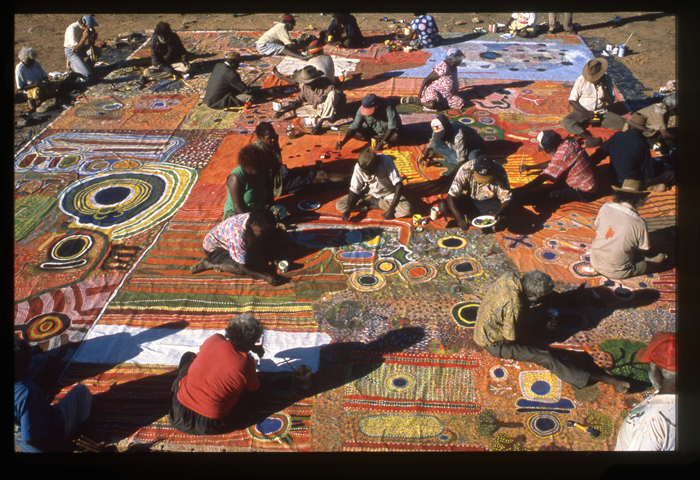

So on 9 May 1997, after four years of meetings, studies and discussions, a group of over 40 Aboriginal men and women (4) from the Walmajarri, Wangkajunga, Mangala and Juwaliny communities and language groups got together at the Pirnini outstation, about six days’ drive south of Fitzroy Crossing in the Great Sandy Desert. The plenary session with the Native Title Tribunal was just ten days away. The following day, on 10 May, Jimmy Pike took a brush and made the first mark, drawing the line of the Canning Stock Route from one edge of the canvas to the other. His fellow artists found their country on the canvas, and began painting.

APRIL 2019, FITZROY CROSSING

In April this year, we travelled to Western Australia to meet with the surviving artists and nominated descendants of deceased artists at the Karrayili Education Centre in Fitzroy Crossing. For many of the 21 artists and descendants present, it was the first time that they had gathered as a group since the 20th anniversary of the painting in 2017. Terry Murray opened the meeting with a minute’s silence for loved ones who had passed or could not be there. From the very start, the entire idea of intergenerational rights could not have been more powerfully expressed.

I followed by explaining that the feeling we all felt during the minute’s silence spoke to an understanding of how much of our world individually and collectively (our landscapes, environments, beliefs etc.) is received in some state from parents, from ancestors and other kin. Meetings like this raise important questions in the context of exhibition making. What do artists stand to gain for having their work on display? What use might others have of architectural exhibitions?

Meetings like this raise important questions in the context of exhibition making. What do artists stand to gain for having their work on display? What use might others have of architectural exhibitions?

The Ngurrara Canvas II is a case in point. The painting is priceless, so it will never be sold. Its value will increase as a result of exhibiting it, but how does a community in North Western Australia benefit, in practical terms, from that increase in value? If we don’t manage to answer those kinds of questions, then we end up repeating the extractive modes of existence that exhibitions are now tying to critique. That changes the way that we begin to think about exhibition making, about how to deploy institutional infrastructure to empower the communities that we are working with in return for their giving us the permission to show their work.

For Ngurrara II is so much more than a painting. It is a strategic intervention in a land rights claim, one that adapts traditional laws and stories about country to produce legal and political effects using aesthetic means. That makes it completely singular in the already rich and complex tradition of Indigenous Australian cultural production. On the one hand, it is a map in the cartographic sense, since it still might be said to point to things. On the other hand, it is far more than a representation; indeed, it is, in a very material and literal sense, country, as those involved in painting it have always pointed out. (5)

As artist Gail Smiler says:

“Standing on and moving around the painting gives you the feeling that the country is nearby, as easy as putting your foot on the other side of the sandhill. That’s how it felt when I was interpreting for the tribunal, standing right on the place we were talking about. But I know for the old people that it is a long way to their country. The painting makes it closer for people.” (6)

It is the expression of law and the way rights to tell stories about country are differentiated among different members of the community. It is a historical narration of the emergence of the landscape. It is a site for ceremonies of cleaning, maintaining, and awakening. It is the embodiment of kin, and the home of ancestors. It is a carpet, you can stand on it, dance on it, let dogs walk on it. It is a plan, both in the literal sense of marking out spaces for artist’s bodies to sit and paint their respective areas, and in the deeper and more profound sense of an intervention that attempts to shape a future action. It is a unique, multi-valent object, one that non-indigenous people will only ever apprehend at the very edges of its meaning.

MAY 1997, THE PLENARY SESSION

With the painting completed, the artists insisted that the hearing take place on their land. It is so that on 19 May 1997, under a tent and a series of tarps in Pirnini in North Western Australia, the Australian Native Title Tribunal assembled to hear evidence in the case called Kogolo vs State Government of Western Australia. Fred Chaney, Deputy Chair of the Native Title Tribunal arrives the Plenary Conference with John Clarke, a representative of the State Government of Western Australia and two other state government employees. The canvas is unrolled before the tribunal. Testimony is given by a number of artists including Warford Pujiman, Spider Snell, Nyuju Stumpy Brown, Pijaji Peter Skipper, Nada Rawlins, Nanyjan Charlie Nunjun, Parlun Happy Bullen, Jukuna Mona Chuguna, Kulyukulyu Trixie Shaw.

When they are called to testify, they walk over to the canvas, they stand on the part of the canvas that is their country, and speaking in the four different language groups of the claimant communities, they explain their culture and law, where they came from, and who they were.

According to one tribunal member, it was “the most eloquent and overwhelming evidence that had ever been presented there.” (7)

NOVEMBER 2007, THE DETERMINATION

In 2007, 10 years after that Plenary Session at Pirnini, Justice Gilmour of the Federal Court of Australia returned to deliver the determination. In the course of delivering the determination, the judge said the following:

“Can I say that in making these orders this Court does not give you native title. Rather the Court determines that native title already exists. It determines that this is your land. That it is based upon your traditional laws and customs and it always has been. The law says to all the people in Australia that this is your land and that it always has been your land.” (8)

***

(1) Kirsten Anker, ‘The Truth in Painting: Cultural Artefacts as Proof of Native Title’, Law Text Culture 9 (2005): 95.

(2) As quoted in: Eleonore Wildburger, ‘Indigenous Australian Art in Practice and Theory’, Coolabah 10 (2013): 204.

(3) As quoted in: Mona Chuguna, Peter Skipper, Tommy May and Karen Dayman, ‘Maparlany Parlipa Mapunyan – We are Painting True, Really True’, Kimberley Appropriate Economies Roundtable Forum, Fitzroy Crossing, 11–13 October 2005.

(4) Ngurrara Canvas II artists: Manmarriya Daisy Andrews, Munangu Huey Bent, Ngarta Jinny Bent, Waninya Biddy Bonney, Nyuju Stumpy Brown, Pajiman Warford Budgieman, Jukuna Mona Chuguna, Raraj David Chuguna, Tapiri Peter Clancy, Jijijar Molly Dededar, Purlta Maryanne Downs, Kurtiji Peter Goodijie, Kuji Rosie Goodjie, Yirrpura Jinny James, Nyangarni Penny K-Lyon, Luurn Willy Kew, Kapi Lucy Kubby, Monday Kunga Kunga, Milyinti Dorothy May, Ngarralja Tommy May, Murungkurr Terry Murray, Mawukura Jimmy Nerrimah, Ngurnta Amy Nuggett, Japarti Joseph Nuggett, Nanjarn Charlie Nunjun, Yukarla Hitler Pamba, Parlun Harry Bullen, Kurnti Jimmy Pike, Killer Pindan, Miltja Thursday Pindan, Pulikarti Honey Bulagardie, Nada Rawlins, Ngumumpa Walter Rose, Kulyukulyu Trixie Shaw, Pijaji Peter Skipper, Jukuja Dolly Snell, Ngirlpirr Spider Snell, Mayapu Elsie Thomas, George Tuckerbox, Wajinya Paji Honeychild Yankarr.

(5) Anker, ‘The Truth in Painting’, 112.

(6) As quoted in: Margo Neale, Sylvia Kleinert, and Robyne Bancroft (eds.), The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture (Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2000), 496

(7) Geraldine Brooks, ‘The Painted Desert’, New Yorker, July 28, 2003: 60–67.

(8) As quoted in: Larissa Behrendt, ‘Ngurrara: The Great Sandy Desert Canvas’, Aboriginal Art Directory, 17 June 2008

***

Adrian Lahoud is the curator of the inaugural edition of the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, Rights of Future Generations. An architect, urban designer and researcher, he has been the Dean of the School of Architecture at the Royal College of Art, London, since 2015. For this article, he wishes to thank Mangkaja Arts Resource Agency, Karen Dayman, Belinda Cook, Fred Chaney, Kirsten Anker, Michael O’Donnell, John Carty, Michael McMahon, Moad Musbahi and David Kim.

Published on 9 August 2019