Tomaso Binga at Mimosa House

Through 20 December

In 1971 the Italian poet, artist and activist Bianca Pucciarelli created the male alter-ego of Tomaso Binga in protest against a patriarchal artworld: in 1977 she married him. The event is commemorated at Mimosa House by a framed portrait of Bianca in wedding dress beside the drag Tomaso, who poses beside a typewriter with manuscript in hand. It’s a typically sharp dissection of gender prejudice from an artist whose visual poems, spoken word performances, installations and interventions mock the privileges afforded to men and embedded in language. Her practice resists the tendency of conventional speech to reinforce norms by returning words to their source in sound and the body – most famously in her Scrittura Vivente, an alphabet formed by a female figure contorted into the shapes of letters – or by reducing it to image, as in the ‘asemantic writing’ that smothers the walls, furniture and mirror of her installation Carta Da Parato (1976, recreated here). As a degraded and weaponised language threatens to overwhelm our public discourse, this exhibition of Binga’s text works, collages and installation feels timely.

Anna Maria Maiolino at The Whitechapel Gallery

Through 12 January

This retrospective of one of Brazil’s pioneering artists moves backwards, giving prime visibility to Maiolino’s works from the past decade. And with reason, so compelling are the haptic surfaces of her sculptural works, so delicate and imaginative her works on paper. At the entrance, a heap of what looks like an enormous noodle made of unfired clay is left to dry, slowly collapsing onto itself; table plinths display what look like fossilised square sections extracted from the ground and hollowed out by insectlike networks of underground galleries, their uncertain status as sculpture or mould reminiscent of the work of Rachel Whiteread; lines become actual threads, sewn into sheets of paper that evoke intricate abstract maps. Only later do you discover the artist’s avant-garde work from the 1960s and 70s, from her antidictatorship woodcuts made during her time in Brazil (Maiolino was born in Italy, and in 1954 emigrated with her family to Venezuela before settling in Brazil) and her formal experiments as part of the neoconcrete movement, to her feminist photographs and Super-8 films. Running through it like a thread (at times literal) is Maiolino’s existential questioning of the cycle of life and the passing of time, and how she fits within it – as a woman, an artist and an exile.

I’ve grown roses in this garden of mine at Goodman Gallery

3 October – 2 November

For its inaugural exhibition, Goodman Gallery (headquartered in South Africa) presents a group show dedicated to collective trauma and the various ways in which artists engage with the subjects of colonisation, forms of violence against the ‘othered’ body and how art might facilitate the process of healing. The exhibition takes its title from Gabrielle Goliath’s most recent collaborative work This song is for… (2019–), a series of ‘dedication songs’ chosen by survivors of rape and re-performed by a singer. Each song is disrupted at a specific point, where a few bars are sung on repeat in the manner of a ‘broken record’ – the effect being that the audience is sonically placed in a position to reflect on the idea of recall and memory. You’ll be able to see this at Goodman Gallery alongside works by artists including Broomberg & Chanarin, Kudzanai Chiurai, David Goldblatt, Alfredo Jaar, Grada Kilomba, Shirin Neshat, Tabita Rezaire and Carrie Mae Weems, where different processes of healing (but, crucially, not curing) are explored within a postcolonial context. Expect to find critiques of identity politics, weaponised language, exoticisation and patriarchal structures that confront received historical narratives.

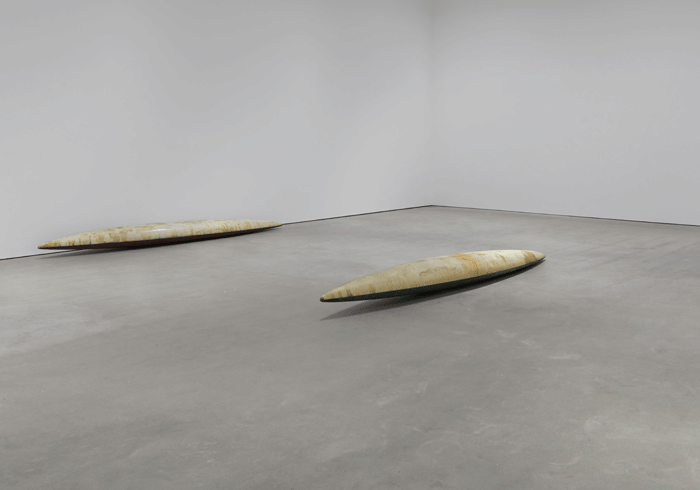

Michael E. Smith, installation view. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London

Michael E. Smith, installation view. Photo: Ben Westoby. Courtesy the artist and Modern Art, London

Michael E. Smith at Modern Art Vyner Street

Through 14 December

Two upturned kayaks lie in Modern Art’s cavernous East End gallery, one in the centre of the floor, one up against the far wall. Someone is bending over and about to place their mucky (probably) hands, palms flattened, onto one of these sculptures by American artist Michael E. Smith. Except they stop, hovering just centimetres about the wood. A low drone emits from under the watercraft. They move their hands and the tone changes. The person, who is clearly in the know, or at least has seen that the work’s material list includes a theremin, starts to inexpertly play the instrument. That the theremin is popularly associated with horror soundtracks sets the tone for the rest of the show. The cold sparsity of Smith’s gesture here is replicated in the gallery’s upper floor, in which just three works are concentrated in one corner. These untitled assemblages operate between the opposing reference points of minimalism and the American gothic, the sole wall-mounted sculpture, featuring a catfish poking out of a backpack, typical of the eeriness of Smith’s beguiling work.

Stephan Dillemuth at Le Bourgeois

5 October – 3 November

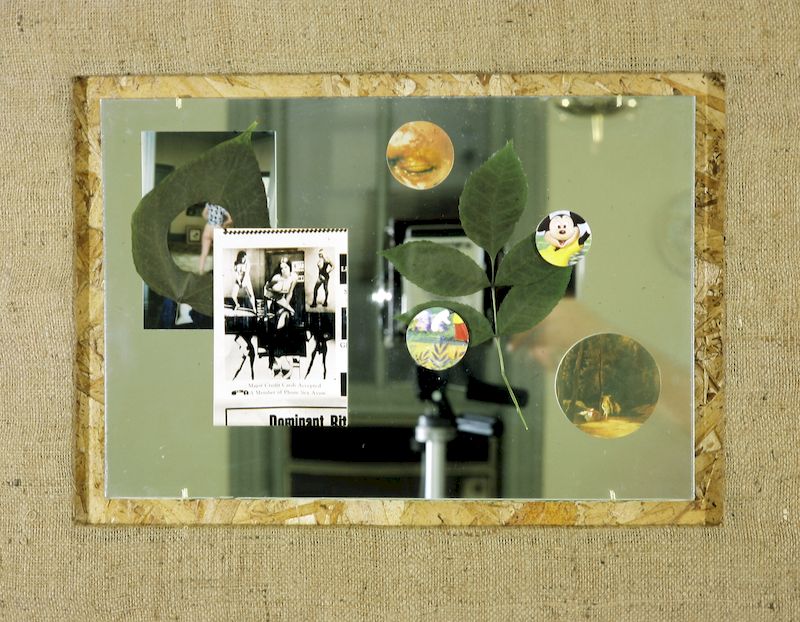

Whether by design or chance, landing in Chicago between 1987 and 1989 was a good life move. Or at least it was in the case of German artist Stephan Dillemuth, who, aged thirty-three, arrived with a stipend from the Bavarian government in his pocket. There – and ArtReview imagines it’s the kind of thing you didn’t really have a choice about – he got sucked into the house music scene just as the likes of the Frankie Knuckles and the Hot Mix 5 DJ collective were breaking onto the global stage. Returning home from the sweat of the clubs, Dillemuth started on his Diskodekorationen (disco decorations) series, mad assemblages that range from a shirt adorned with pornographic images to mirrors, some obscured with marker-pen scribbles, featuring postcards and Disney illustrations. They marked a major break from Dillemuth’s earlier figurative paintings, and laid the groundwork for the sculptures the artist has become known for since. Brought together by curator Saim Demircan at this South London artist-run space, these earlier works are definitely worth a break from the madding crowd.

Online exclusive, 2 October 2019