Before it was chiefly famous for being a city to which newly hip other cities were compared, Berlin was known for two things: a Wall (and, since 1989, not having one) and nightclubs. The German city’s institutions are not going to let you forget either of these ‘selling points’ during Berlin Art Week, it’s annual art-institution/art-fair/private-collection jamboree. Walking Through Walls, at Gropius Bau, is not an ode to the Kool-Aid Man, but naturally takes borders and divisions, noting the 30th anniversary of the end of Berlin’s physical separation (political reunification came a year later, in October 1990), as its subject. Expect iconic works by Marina Abramović and Ulay (ArtReview guesses it will be The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk, performed by the couple in 1988 as they were ending their relationship, in which Abramović walked from east to west and Ulay from west to east along the top of China’s Great Wall, meeting, and then parting) and Javier Téllez (again, ArtReview suspects, but does not guarantee, the project in which the artist shot a human cannonball over the Mexico–US border).

Once the Wall (Berlin’s, that is) did come down, East and West found the dancefloor to be one of the best places for catching up with neighbours. Club and bar promoters had plenty of empty property to play with, and the city’s liberal attitude to impromptu parties was manna (though other edible substances may also have been involved) to ravers legislated against in other countries (such as those criminalised by the UK’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994). No Photos on the Dance Floor! at C/O Berlin documents three decades of partying. Naturally Wolfgang Tillmans is included, but so are filmmakers Steffen Köhn and Phillip Kaminiak (for After Hours, a 2013 video capturing a bunch of animals let loose in the legendary – and mysteriously empty – Berghain nightclub) and photographer Anna-Lena Krause (whose 2019 series The Aftermaths consists of portraits of patrons of the same club, taken as they emerge wide-eyed into daylight).

Berghain is notorious for its entry policy, casually turning away even the most ardent of would-be clubbers, no reason given. Certainly Berlin’s casual debauchery of the 1980s and 90s has given way to a self-conscious cool. Which leads ArtReview neatly to the much-feted performance artist Anne Imhof, who is showing a Galerie Buchholz (though Art Week focuses on museums, naturally the commercial galleries make an effort too). Advance information states that Imhof and her cohort ‘do not appear as observant performers acting within the effects of pre-existing power structures. She works with them.’ This frequently translates as icy collaborators who look like they’ve stepped out of the pages of a style magazine to be choreographed into a series of opaque movements and actions. For this show, however, there will also be objects: ‘Imhof sinks the horizon of an unbearable everydayness – through us, its bearers. She collapses the horizon, spreads it across paintings, repeats it as a Newscast Label, forces it into a vertical position in the form of test images of catastrophes, elevates it on high seats for her performers, serves it to us on trays… Sex as form.’ OK.

Berlin’s days of cheap rent and empty buildings have all but ended, but 50km south of the city, Pablo Wendel and Helen Turner came across a power plant that had been switched off in 1994, when the energy company that ran it went bust. The two have set about turning it into a gallery and studio complex: so far, so cliché. Yet here’s the cool bit: E-Werk Luckenwalde will also be back in the power business, generating electricity through a process known as biomass pyrolysis, which will then be sold to the national grid, with profits funding cultural activities. Nicolas Deshayes inaugurates the centre with an exhibition of his disturbing, blobby radiator sculptures; works that, like their host institution, mix art with utility and are plumbed into the gallery heating system.

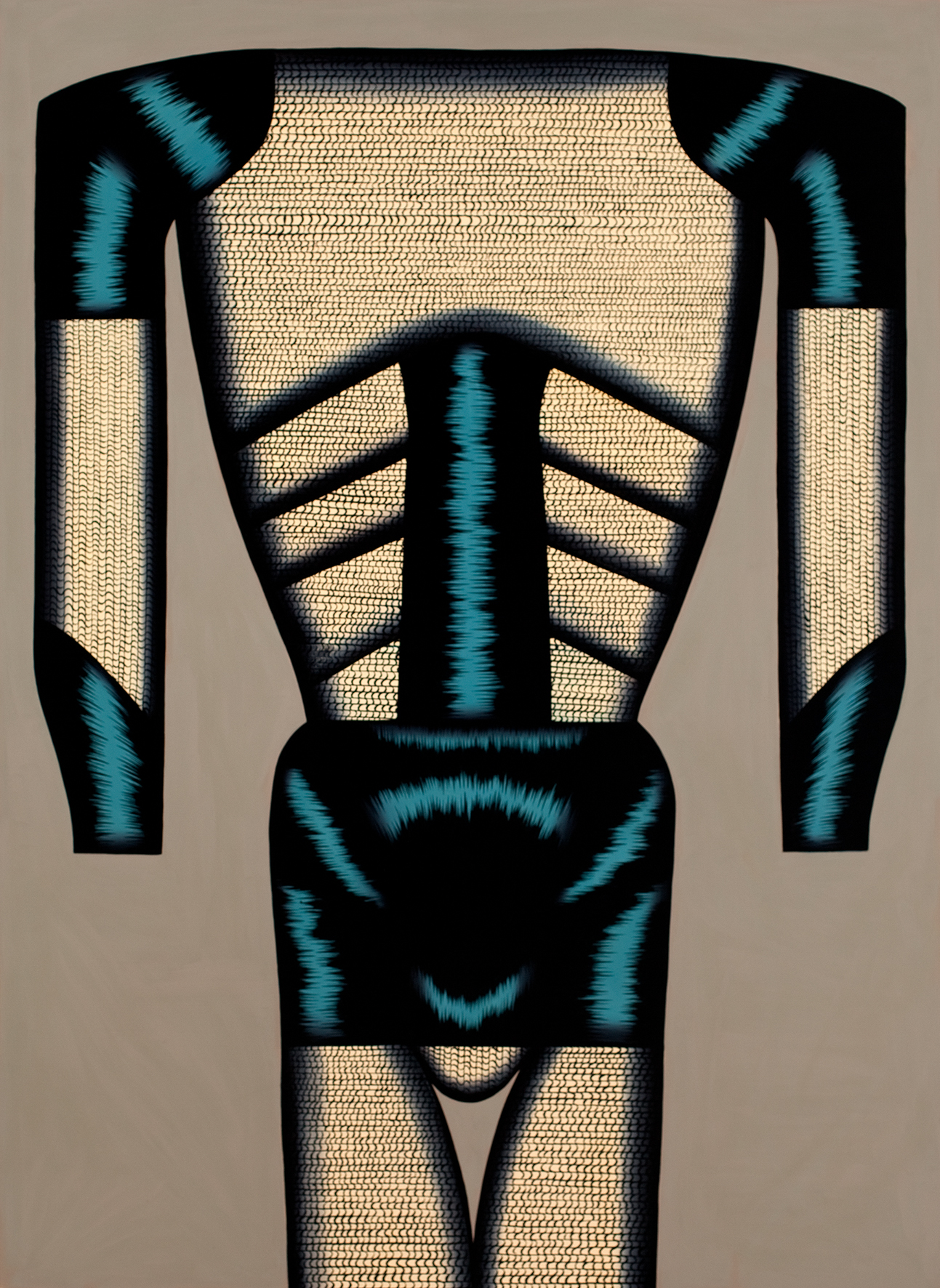

Berlin has long become a brand, and as we know, brands are powerful things, pulling in the punters and getting people (and, er, editors of websites) to sit up and take notice. This is something the Chicago Imagists, a group of painters associated with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago during the 1960s, understood intuitively. By giving themselves a moniker, they proved more powerful than the would have been individually. One of their number, Christina Ramberg, who died in 1995, is the subject of an exhibition at the KW Institute. In a move that marks this show out from other recent retrospectives of the gang, the curators will show Ramberg’s work, typified by her stylized paintings of corset-wearing bodies, with work by younger artists, including Alexandra Bircken, Ghislaine Leung and Senga Nengudi.

Online exclusive, 13 September 2019