The map for Documenta 14 lacks all but the most major street names. And the scale is slightly off. They’re petty details to note in a review, and though the 2017 edition, like its 13 predecessors, asks viewers to ramble about town (most of the action takes place around the Friedrichsplatz), the map is quite important to this edition, which operates on the idea of territory.

In lieu of a theme, an every, or an all, the biennial is arranged as a collection of nodes. There are micro-exhibitions about tried and true subjects: Neue Neue Galerie, housed in an abandoned post office, focuses on labour; Documenta-Halle collects works surrounding the idea of the script or open score; the Museum fur Sepulkralkultur, an institution dedicated to death memorabilia, houses a discussion about the body; Neue Galerie is transformed into a meditation on privilege, wealth, and authority of the historical museum itself; and the Fridericianum, the ‘world’s very first purpose-built public museum’, opens its doors to the nearly bankrupt National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens (EMST), displaying a portion of its collection in exchange for using the space as a primary venue for the initial Athens chapter of Documenta 14 – in an attempt, as one wall text explains, to chart a new humanism through the artworks on display. To a cynical eye, this latter gesture ghettoises the ailing Greek institution, turning it into a readymade stand-in for the exhibition’s stated motivation to be ‘Learning from Athens’ – especially when the post-war collection perpetuates the idea of the contemporary or contemporaneity, a defining characteristic of globalism.

Yet, to an American eye, this move resembles the scrappy, by-any-means-necessary methodology that defines the semi-autonomous institutions that, unlike European organisations, operate with relative financial independence from the State – they don’t have the same direct responsibility to the public, which, for better and worse, affords them a malleable position in the economy of symbols. From this perspective, what is perhaps Documenta’s grandest gesture embodies the exhibition’s generous spirit, as well as its central irony: any individual artwork offers a metaphor for the exhibition, but that is only possible once we experience all (or nearly all) of it on the whole.

Staged throughout this city of students, the show invites viewers to contribute their experience and participation

There’s an ambient learning from that Documenta promotes. Staged throughout this city of students, the show invites viewers to contribute their experience and participation. It is a brave thing to risk what can often appear as an uncritical ‘my truth’ approach, incapable of imposing a criterion of evaluation in the spirit of openness. But curator Adam Szymczyk and his team are thorough, giving plenty of room to each project. It shares a sense of purpose that feels well-lived, a form of stewardship that allows viewers to take responsibility for their truth amidst the irresolvable scale of the show. Does it always work? No. Some galleries are crammed, though it seems as though the biennial embraces the roving, anarchic condition inherent to walking around the city, and deciding what’s art. A preponderance of psychedelia at Neue Galerie offers some insight into this altered state.

Documenta leans heavy on entropy, a choice perhaps inspired by the late Christopher D’Arcangelo’s performances and proposals from the 1970s. Here, they are collected in three binders, and displayed on a rather severe metal desk under the artist’s painting that reads ‘POST NO ART’ on a piece of Plexiglas. D’Arcangelo is famous for his tautological statement, “When I state that I am an anarchist I must also state that I am not an anarchist to be in keeping with the […] definition of anarchism. Long live anarchism.” In one protest performance, he inscribed the words on his body and chained himself to the main entrance of the Whitney Museum of American Art. The performance, a statement about passage and thresholds, concerns how the body is channelled by various institutional forces, using it as the medium of resistance, barring entry to the museum. But within the present context, it appears Documenta was equally inspired by the archive that D’Arcangelo kept, and how those materials circulate today. I was asked not to photograph any of the archival materials, a telling example of how there are other considerations than fracture afoot throughout the show.

A text discussing D’Arcangelo’s work in one of the binders uses the idea of an anaphora to describe the experience of his work. It is a rhetorical device, a repeated phrase upon which we layer meaning, something recognizable from some of the more affected performances of a pastor (i.e. Oh lord! Save me. Oh lord! We pray; or, not from a pastor, as in ‘fuck you you fucking fuck’). It’s sort of a linguistic chain reaction, a way for meaning to bluntly appear through repeated experience, rather than the logical, and linear progression of an argument. And in many ways, this is how the exhibition functions, a collection of slogans or protest chants.

Though it edges toward the moral dictats of democracy, it makes little fuss about whether these projects are art or not, preferring that art remains more unruly

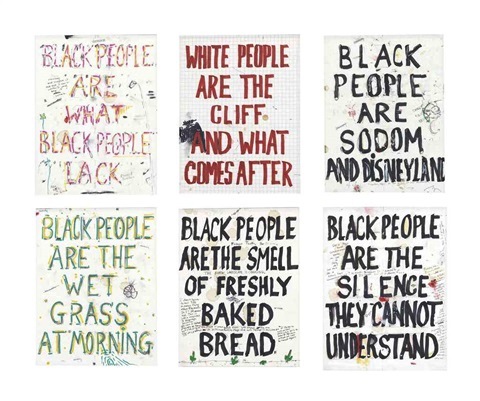

The show’s structure certainly challenges hierarchies of value, though if everything is equal, it can therefore be randomised. How the exhibition navigates this challenge is to adopt various political causes. Though it edges toward the moral dictats of democracy, it makes little fuss about whether these projects are art or not, preferring that art remains more unruly. We are better off saving our energy for the larger issues contained therein, and for all the show’s didacticism, it lets the works themselves do the talking. Protest posters are frequent motif: feminist posters by Lala Rukh declare ‘The unholy Trinity: men, money, morality’; Sanja Iveković proposes revolutionary actions; and the inanities of Pope.L’s absurdist series Skin Set Project (1997–) declare ‘BLACK PEOPLE ARE THE SILENCE THEY CANNOT UNDERSTAND’ and ‘WHITE PEOPLE ARE THE CLIFF AND WHAT COMES AFTER’. They complement Annie Sprinkle’s ecosex walking tour: with schmaltzy, day-time-TV enthusiasm, she, along with a cohort of collaborators, staged a march to the earth’s clitoris (according to Sprinkle and her collaborators, the one in Kassel is one of many), folding trans sexuality and environmentalism into a raunchy vocabulary, a resistance by explosive orgasm. Other examples fall flat, however, such as the Listening Station, which presents recordings from the workshops and talks that took place in Athens alongside other radical musical compositions, and sundry other audio recordings. It approximates a listening party combined with political activist meetings, but it is tucked into an isolated corner, and lacks the improvised group character that Sprinkles’ tour possessed, which is one important way that one work can connect us to the whole. I am a happy, card-carrying ecosexual thanks to the tour.

Does Documenta have to be about Kassel? Do the works have to be made here? Do we require international exhibitions to be counterbalanced by localism? Do we need to see how the events of the world affect us here at home? Or that they create a notion of home for us ‘viewers’? Or that artists communicated with locals? Or that the exhibition itself constitutes its own micro community, and, like the VW plant on the outskirts of the city, is the primary industrial driver to this temporary aggregation of artists and thinkers, having paid each participant a participation fee? Or is it closer to the situation illustrated in one tram stop: next to Hans Haacke’s posters hopefully stating ‘We (all) are the people’ in numerous languages is an image of a white guy with his crotch seemingly on fire, humiliated in front of his doctor?

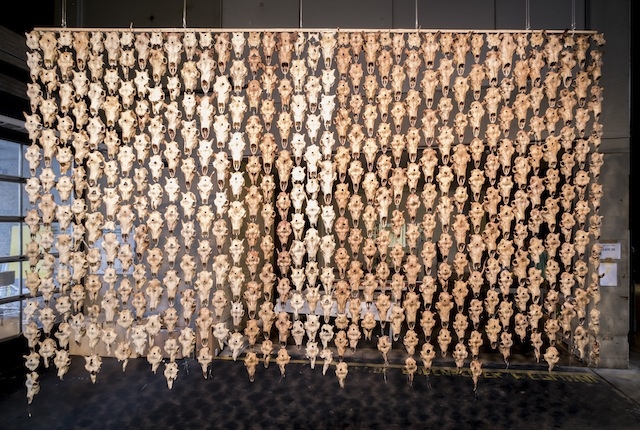

Though these questions abound, Documenta is by no means so unabashedly punk or impetuously laissez-faire, as the focus on and crucial presence of indigenous artists and issues attests. In fact, if I were to select a single artwork to map the exhibition, and inscribe the territory that contains our experience, it would be Sami artist Máret Ánne Sara’s Pile o’ Sápmi (2017). It is a light box leaned against the wall; the image depicts a snowy pyramid of reindeer heads topped with a Norwegian flag as if to mark the spoils of conquest. The Sami is a group indigenous to the arctic territories spanning Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, and Sara solicited the heads from her community’s herds – the source of their livelihood and foundational to their nomadic traditions and connection to the land. Sara staged the intervention at the courthouse where her brother was suing the government over recent legislation that authorised the killing of what the government deemed overstock in his and other herds. The trial was emblematic of the Sami’s statelessness and vulnerability, and though Ánne Sara’s brother won the trial, the verdict is pending in another court. While migrations from war-torn countries has destabilised the world, here is an example of a migratory population whose definition of a state is not judicial, but a matter continually observed, and firmly active. Rather than chart a new course, however, it is a matter of learning from the map.

Epilogue

In one of the binders, D’Arcangelo, outlines a proposal to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, asking it to open its doors to anyone who would like to submit an object for a week. People may submit anything they like, with emphasis on everyday objects, and the proposal suggests that the museum take out TV and radio ads to publicise the project. The anarchic reassessment of value is therefore contingent on broadcast, and doesn’t actually need to happen to plant the seed in a potential participant’s head.

At nearly the beginning of your trip to Kassel, you get stuck at Newark Penn Station for way too long. You feel like you’ve done your job, having seen the museum shows where you live before you left (and not even on the last day before they close), but you’ve left your See Saw preferences entirely underutilised, and your in-app map is a cluster of pins that represent galleries you won’t be visiting this month. You open an email about another Lower East Side gallery closing, or, really, like others, turning into a consultancy. You ignore the dozens of Liste and Art Basel emails, because you won’t be attending, at least not in person, or, at least not of your own volition. Images of Basel, Venice, Kassel, and Munster have flooded your feed for weeks. You consider deleting the app to maintain your sanity while attempting to file a review, but then you remember that it confirmed an important detail: you won’t be running into your ex-girlfriend. And, in any case, you’ve suffered from serious FOMO the last three weeks when you thought this press trip wouldn’t happen, and by the time you’ve recovered from the assault of the Athens edition of Documenta, you’re on a plane, apologising to your friend for missing her opening in New York. At this point, you watch two movies on the plane, both of which take place in American cities where you’ve lived and happen to centre around McDonald’s franchises. The tension that held your world together, you realise, is mired in anxiety and compounded by guilt, and you welcome landing in a place where you don’t know what anyone is saying. It’s been said already anyhow, because you’re a week late to everything. You sleep one hour on the plane. You take the train to Kassel. You can’t believe that the film Coming to America, which you’ve only seen for the first time, hinges on such a literal joke about Queens, New York. You’re jetlagged, a condition that finally leaves you able to be guided by someone else’s terms. You fall asleep while walking. You’ve just undergone a clusterfuck of emotional and physical decompression. It’s at this point, the very first step in a new place, that the map is the experience.

Published online 16 June 2017