Skye Sherwin tracks the resurgent interest in the late Philippine painter

In the short documentary Wild at Art (1995) the late painter Pacita Abad explains how she was once detained in Hawaii, suspected – because she was from the Philippines – of travelling with a fake passport. This brush with systemic prejudice led to her series Immigrant Experience (the works shown here are dated 1991–94), huge quilted canvases painted and embossed with embroidered forms using the ‘trapunto’ technique. They occupy over half her exhibition at Spike Island, where they hang, flaglike, from the ceiling.

But this isn’t a fight-the-power protest art the story might suggest. Rather Abad filtered what she learned from fellow immigrants from places as diverse as Cambodia and Korea in works of colour-saturated affirmation. We’re shown people’s day-to-day challenges and aspirations: at work, negotiating the school system, getting married or shopping for groceries. America’s land of plenty is evoked in glowing street signs and trolleys brimming with branded goods. These are rendered with all the vibrant appeal of the flora and fauna, costumes and traditions from beyond the US that also feature in these works.

Though Abad studied art in Washington, DC, it was the traditions of the countries she travelled to in Asia, Africa and Latin America she related to most. Her paintings incorporate everything from batik to macramé, mirror embellishments and ink drawing. Each surface is intensely worked with dots and dashes of pigment and stitching, sewn-on shells, sequins and beads, real clothes and cutup dyed fabric, and the abstract trapunto paintings that occupy the rest of the gallery are a kaleidoscope of this technical cosmopolitanism: an early work composed of swirling, dripping organic shapes is inspired by the peeling walls of her home country’s capital, Manila. The series Oriental Abstractions (1984–92) uses Korean ink-brush painting as a starting point for screen-printed, mosaiclike constellations of crescent moons elaborated with dots, latticework and zigzags. Trippy titles like Liquid Experience (1985), a work in which hot red mountainous forms recall Japanese landscape painting, suggest the San Francisco counterculture scene that, having fled Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorship during the 1970s, first nurtured her creative sensibility.

Though her work was not unknown in the US, Abad worked largely outside the Western artworld, making and showing paintings in the countries she visited. She was invested in a broad and local audience (creating public artworks like her 2004 covering of Singapore’s Alkaff Bridge in multicoloured patterns) and favoured unconventional methods of distribution (decorating dresses and even a dinner set). But with the recent drive to address art history’s predominantly white, male and Western-centric blind spots, and a resurgent interest in fibre art, her paintings have lately gained exposure, with major museum acquisitions, a survey in Manila and inclusion in international art fairs. Dubbing herself a ‘woman of colour’ with cheerful double entendre, she approached identity in a manner distinct from the nuance of today’s debates. Yet her sense of globalist empathy speaks enthusiastically to our own, particularly in this fraught moment, when borders are closing.

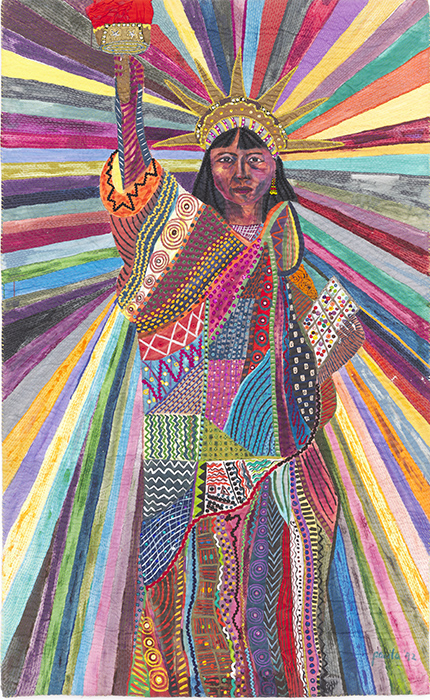

What rescues her project from exoticism is how Abad approaches her material as a fellow outsider, keen to give other overlooked people and creative traditions a platform through her painting. Her labour-intensive process, the works’ size and their installation – here, hung from the gallery’s lofty ceilings – all emphasise that this is a project of everyday monumentalism. The effect is especially striking in L.A. Liberty (1992), in which a brown-skinned Statue of Liberty poses triumphantly in an intricately decorated patchwork dress against a rainbow sunburst. She’s ‘a woman of colour’ in every sense and, like all of Abad’s work, an exuberant banner for multiculturalism before the term became a staple of artists’ discourse.

Pacita Abad, Life in the Margins, Spike Island, Bristol, 18 January – 5 April 2020

From the April 2020 issue of ArtReview