The four-day festival, curated by Vincenzo de Bellis, was inspired by the ancient Greek concept of xenia

A triptych of paintings rests against the rough brick walls inside the Castello Carlo V, a castle-turned-temporary-gallery in Monopoli, Italy. On the left, a dark ship appears heading for the viewer, all concrete grey and shadowy black. On the right, the same dark body heads in the same direction, or perhaps the opposite – the top half appears to have been scratched out or aggressively brushed over. In each, a solid circle sits at the centre of the piece, placed in and seemingly on top of the painting. The central piece expands this circle, an abstraction filled with expressionist brushes and details. People of the Future (1997) by Edi Hila was made in remembrance of the 84 Albanian migrants who in 1997 lost their lives trying to flee the Albanian civil war to Italian shores. The victims died when an Italian navy coastguard enforcing a de facto blockade collided with and capsized the vessel (widely known as the Tragedy of Otranto). In the room around the triptych, old cannons lie rusting and dormant, but pointed seaward. When the space empties, sounds of the Adriatic waves outside the walls filter through. A little serendipitous; a little inspired.

Hila’s work is part of Panorama Monopoli, a four-day festival by the Italian art consortium Italics (a national network of commercial and private galleries), presenting 60 artists across 20 exhibition venues and curated by Vincenzo de Bellis – this is its second edition, hosted in a different Italian town each year. Collecting works from the fifteenth century through to the contemporary (often making a somewhat laboured point of contrasting the former with the latter), this edition’s curatorial theme is based on the Greek concept of xenia, that of hospitality to the foreigner, a ritualised friendship based on reciprocity. And Monopoli, a small coastal town stationed some 40 kilometres down the Apulian coast from Bari, has a turbulent history of its own, having changed hands between Byzantine, Norman, Venetian and Spanish rule. Its sea walls, built to counter Ottoman pirates and now wearied by the elements, still stand tall around the town.

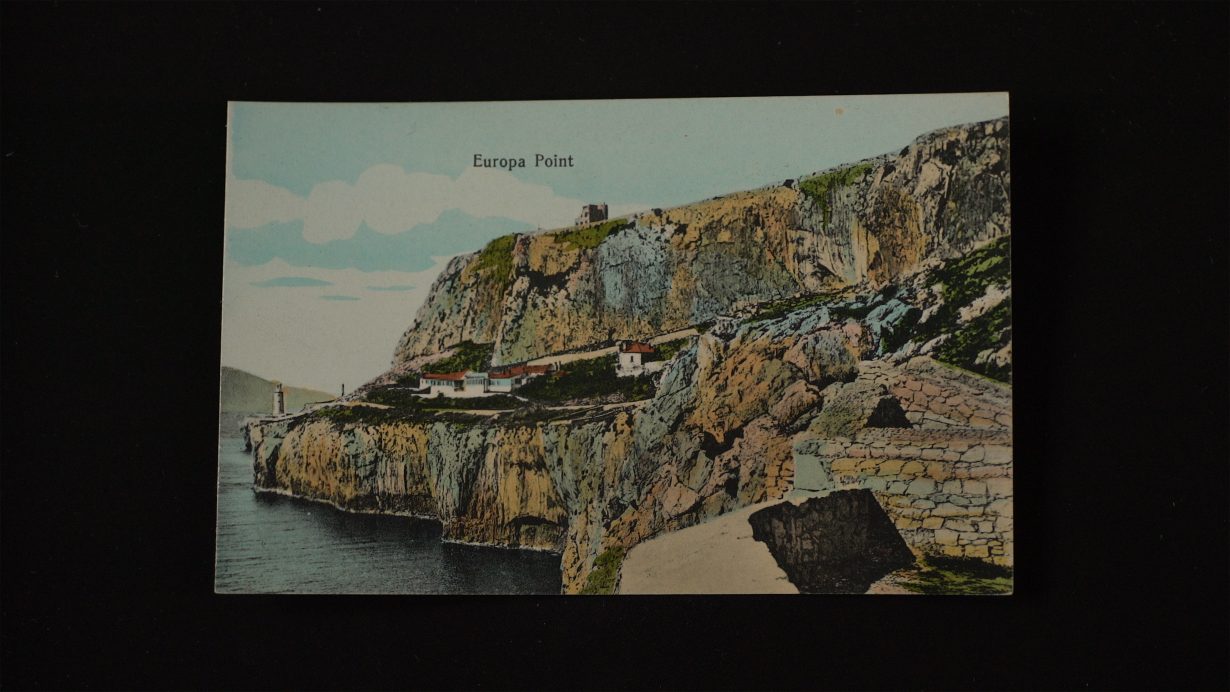

None of which is necessarily unique for a port town, but when an art festival backed by municipal and private money descends, filling the town with its works and international attendees, how can the history and the contemporary exist in harmony? It is no surprise that Panorama’s best works speak to this weight of history as an ever-present sensation, or a dislocating force. At Complesso San Leonardo, a former monastery and school refurbished then reopened for Panorama, Swedish/Brazilian artist Runo Lagomarsino’s film Europa Point (2019) depicts a 1970s postcard of the Strait of Gibraltar against a black backdrop. Smoke begins to cloud the shot as the card burns seemingly from behind. The edges begin to curl, blacken, then burst into a few seconds of brilliant flame as the heat meets the chemical ink. When the flame dies, we are left with the embers and a discoloured, ashen card: its parts slowly break apart like continental drift in time-lapse. As a far outpost of Europe facing Africa, sitting at the gate between the Mediterranean and the North Atlantic, the Strait in this work is synecdochical for political and geographic boarders imbued with tragedy. But Lagomarsino declines the ease of straight melancholy: in the almost entirely ashen card, the letters of ‘Europa’ can be made out. He leaves room for renewal.

Alongside the town’s turbulent history of trade, conflict and rulership, exists an older and more fundamental tradition. During the construction of the town’s cathedral in the early twelfth century, a pious man of the town is said to have seen in three recurring dreams the Madonna come to Monopoli’s shore. Determined to prove the dream’s veracity to the incredulous bishop, and to himself, he went to the port’s bay and found a stranded raft. Atop the woodwork sat an icon depicting the Madonna with Christ in her arms, which is now built into a raised chancel in the Cattedrale Maria Santissima della Madia. The occasion is celebrated annually in Monopoli, and one such event was attended by Matteo Fato, whose work senza tempeste, senza naufragio e senza alcun merito nostro, (2022; without storms, without shipwreck and without any merit of our own) populates the Chiesetta San Giovanni. Impressionist paintings of the Monopoli seascape at such celebrations hang on either side of the Chiesetta, while planks and beams of wood are scattered over the floor and fixed to surfaces. As an education of this tradition and a suggestion of the contemporary Monopoli’s inescapable coastal role as a point of import, arrival and acceptance (it took in Albanians as the Soviet Union collapsed), not a fortress of defence, the work carries a poignancy beyond the somewhat underwhelming technical feats of his paintings – and is a satisfying instance of the festival engaging directly with its locality.

You’d imagine that uniting these works under the theme of xenia, then, could amount to something of a poetic and a political statement, but it doesn’t. In his curatorial notes, De Bellis is at pains to avoid a more overtly political positioning: ‘This is a year when mass migrations between the various world borders have not ceased, and because of our position overlooking the Mediterranean, we see them coming mainly from the East, the Middle East and North Africa,’ he begins. ‘Panorama Monopoli cannot and must not be a political exhibition in the most immediate sense of the term… The selection focuses on universal themes that inspire a wide variety of interpretations.’ If it sounds paradoxical, that’s because in many ways it is. Universality is often an oversimplification of concept, and supplication to ease of understanding, that can obfuscate. And with a looming election in Italy that, by most accounts, will see victory for the far-right Fratelli d’Italia (whose leader Giorgia Meloni counts tweeting a video of a Ukrainian woman being raped by a Guinean asylum seeker among her abhorrent actions), hiding behind universality looks, at best, deferential to power. Edi Hila’s paintings or Runo Lagomarsino’s film, for example, are more than capable of speaking for themselves, combining the textures of history, dislocation, and tragedy with an unequivocal emotional core. That essence, surely, must be what Panorama Monopoli is really for.