On the Indonesian spice trade, land exploitation and the Indigenous practices that might reshape our relationship with Earth

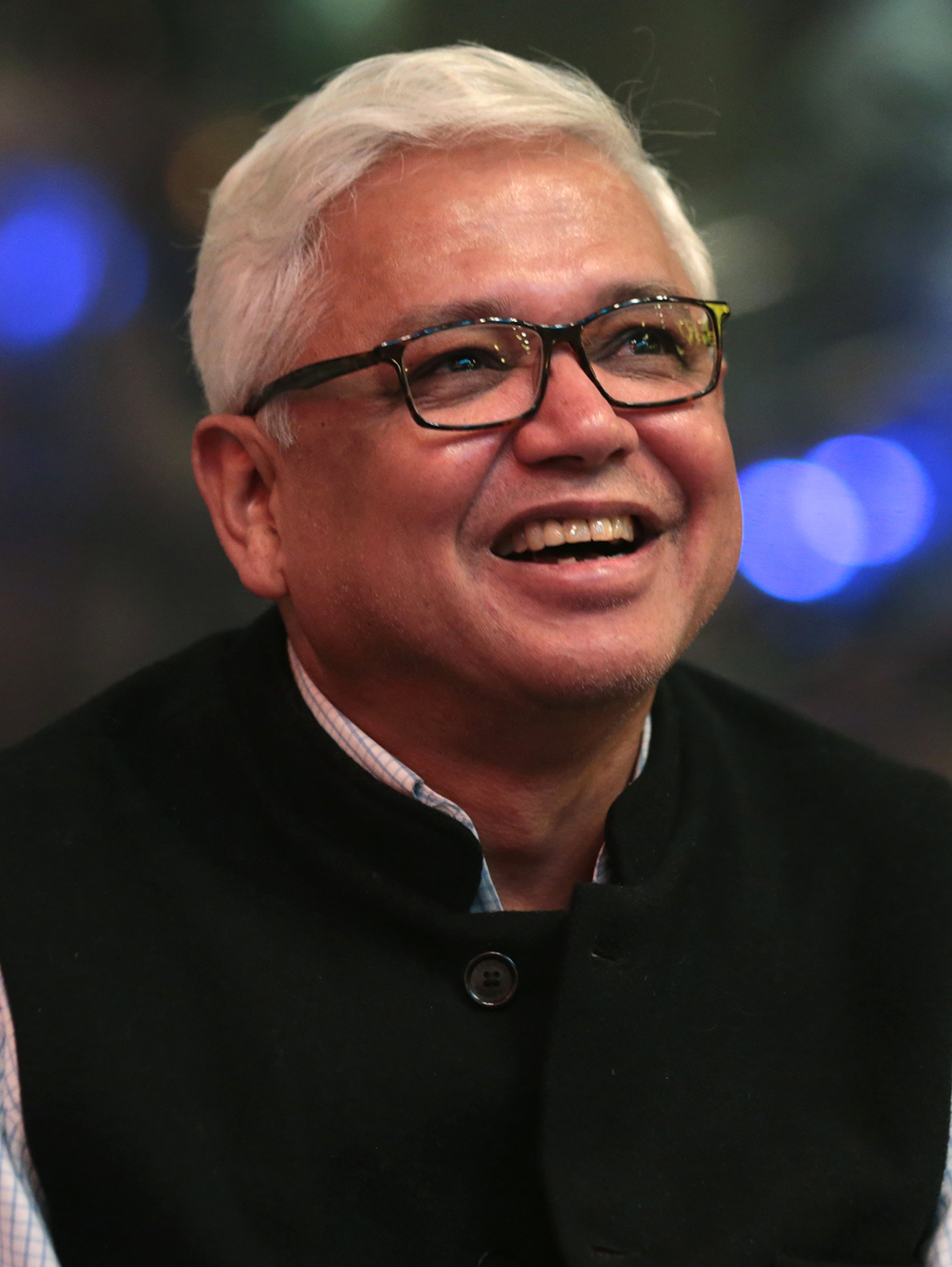

What measures might mitigate the fast-worsening climate emergency are widely known, even if, despite the urgency of the situation, not adequately acted upon. Amitav Ghosh – the Indian novelist whose 2016 book, The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable, was a polemic on the failure of humans in understanding and acknowledging the scale and violence of climate change – knows this, and consequently his new book does not seek to reiterate such solutions. Instead, he traces why so much of humanity began to treat the Earth as an object to be exploited and profited from. In doing so he implicates Europe’s colonial ambitions from the seventeenth century onwards.

Ghosh argues that the dissociation of human beings from the natural world, and the dismissal of Indigenous, tribal understanding in which landscape and local nature meant much more than usable resources, was a metaphysics that emerged in Europe as colonial empires were making inroads into the Americas and eastwards. Ghosh employs the gruesome history of the Banda Islands, administered from Indonesia, as a point of departure to critique the colonial mindset of ‘official modernity’ and how it continues to determine geopolitics today.

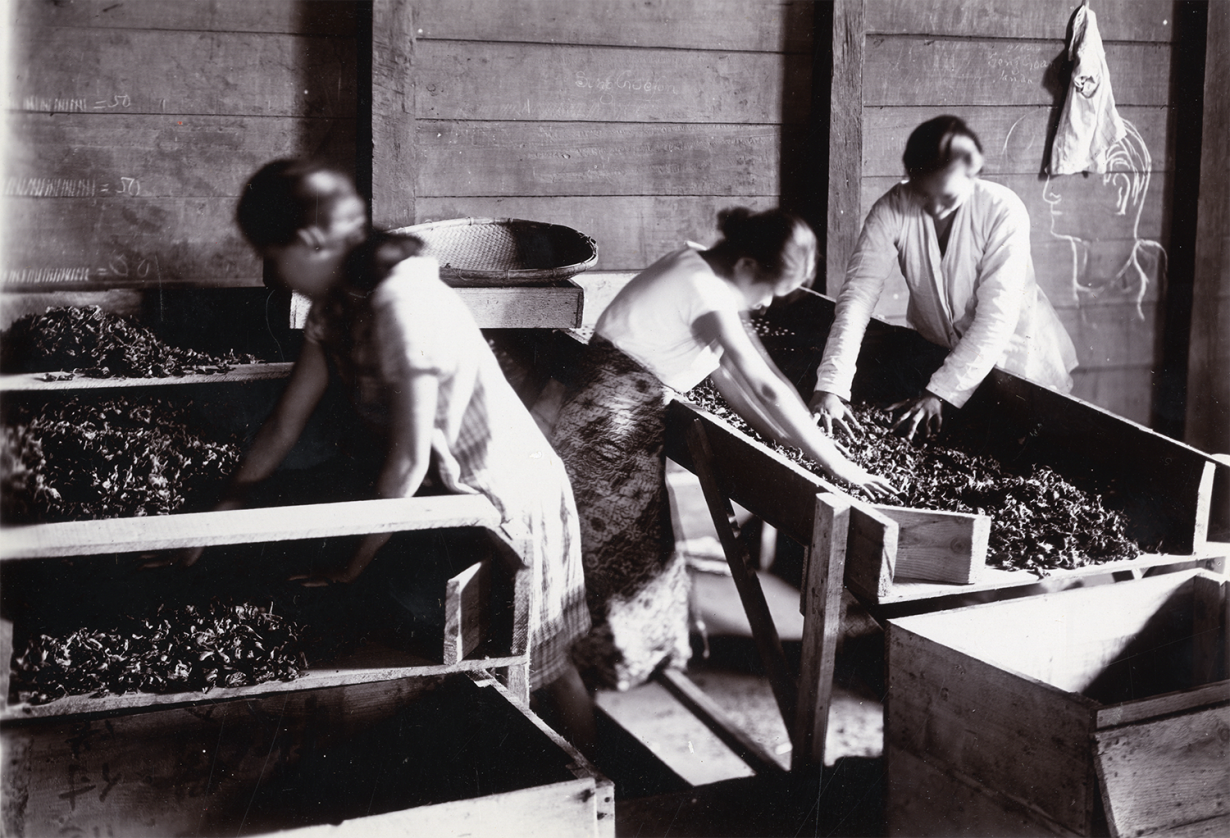

During the 1620s, thousands of inhabitants of these spice islands were massacred by the Dutch East India Company, to secure its monopoly over the highly lucrative trade in nutmeg, a spice that then grew only in the forests on the islands. Naturally, the race to secure steady supplies of nutmeg and clove, which only grew on the neighbouring islands, was one that first the Dutch, then the English, fought fiercely to win. ‘The spice race was the space race of its time,’ Ghosh writes.

Ghosh chooses to focus on the Americas and Europe while examining how the climate emergency today is both an extension and a result of imperialistic policies going back some 500 years. Some of the English mercenaries who eliminated the Bandanese were part of expeditions that also killed thousands of Amerindians. With trade, commerce and expansion of territory, genocidal policies and the terraforming of every landscape into ‘neo-Europes’ went global. The settlers, beginning with the Bandanese and carrying it everywhere they went, pursued a policy that was not just genocide, but a greater violence that can only be called ‘omnicide’ – the desire to destroy everything, Ghosh writes. In the process, Indigenous knowledge and value systems were violently suppressed, the songs, stories and intuitive awareness people had to connect with the land (as opposed to a resource called ‘land’) were erased and First Peoples were rendered mute by the settler colonialists. This, Ghosh argues, ‘enabled the metaphysical leap whereby the Earth and everything in it could be reduced to inertness’.

The Nutmeg’s Curse draws on layers of modern geopolitical developments – from mass migrations and political breakdowns to environmental degradation and the current pandemic – to understand just how entrenched the colonial mindset remains in developed societies. While the bulk of his reportage and references keep the narrative arc of the book mostly in the Global North, Ghosh acknowledges that ‘the most voracious agents of extractivist capitalism today are probably those who came late to settler colonialism, like the elites of many Asian and African countries’.

The book often returns to episodes from Indigenous history, taking cues from shamans, scientists and what is being called ‘Traditional Ecological Knowledge’ to suggest that viewing the world only through a prism of mechanistic politics without including nonhuman voices that are ‘all our relatives’ can no longer pass muster. Identifying that a vast majority of human beings live today like the colonialists once did, taking and taking from the Earth as if a future was absolutely guaranteed, Ghosh urges an urgent restoration of nonhuman actors – the land, the animals, the spirits – and adoption of vitalist politics when we tell ourselves stories about the Earth and our relationship with it.

From the January & February issue of ArtReview