At Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin, the artist has based his paintings on computer projections of night skies in 2100

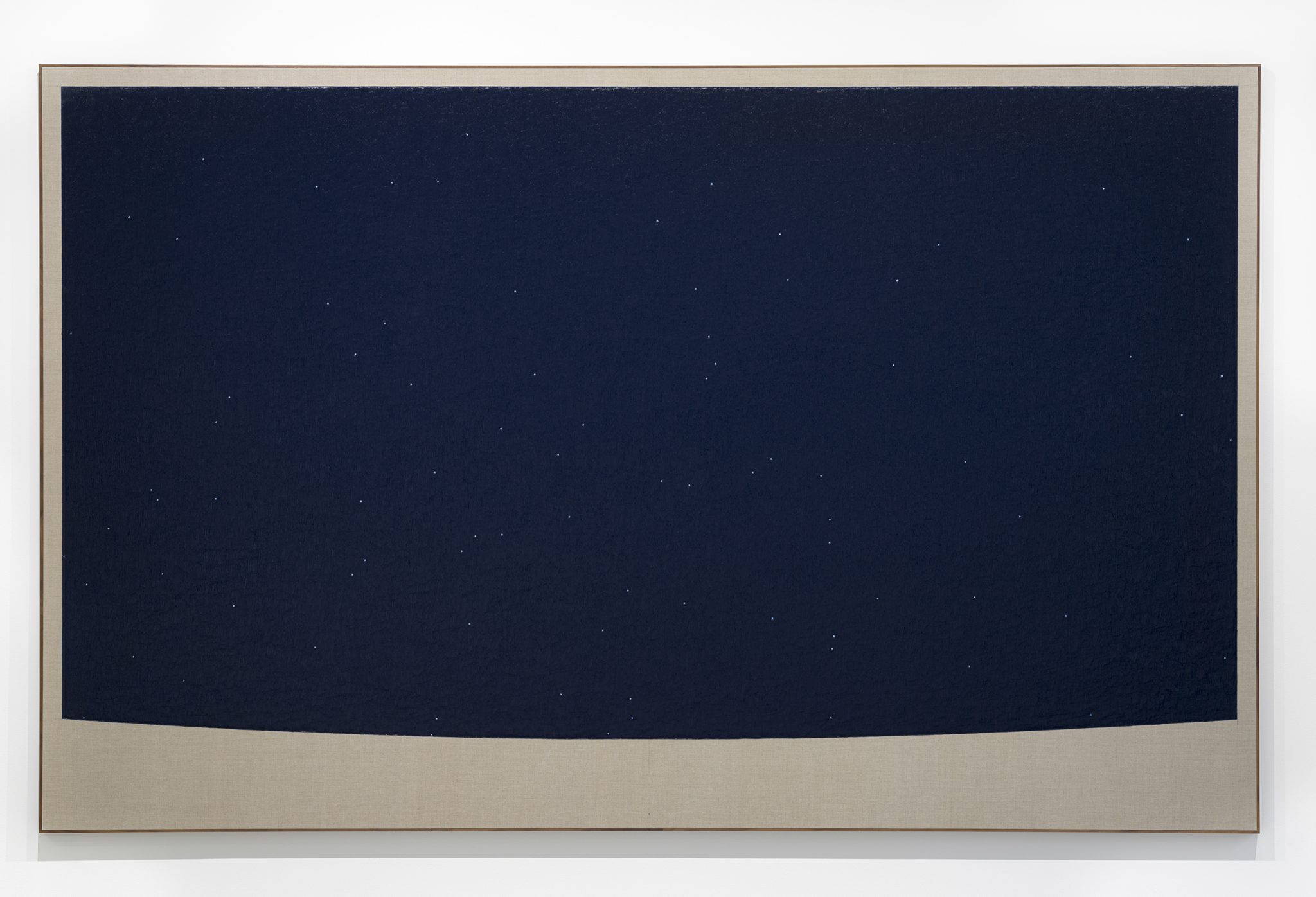

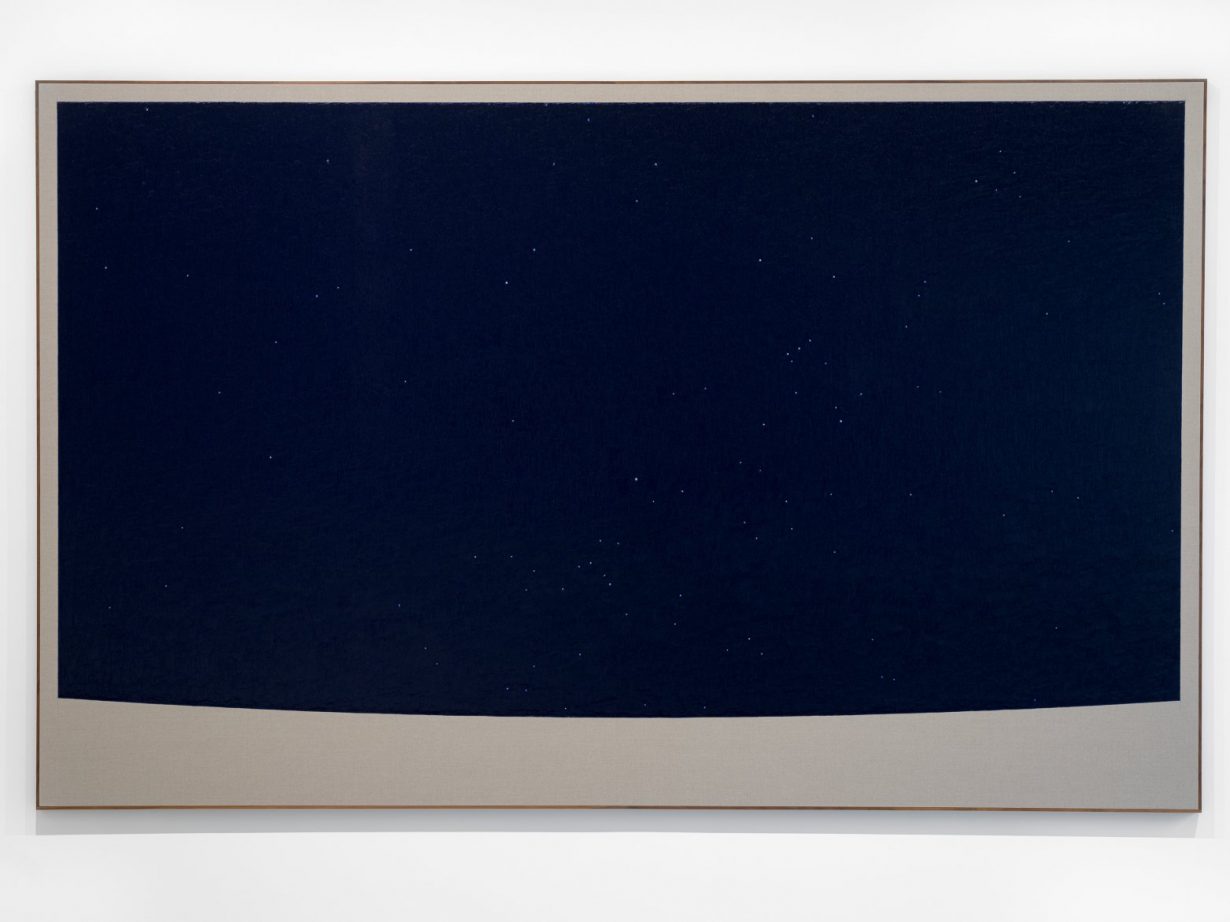

If many gallery exhibitions nowadays consist of one work repeated with small variations, Paul Fägerskiöld’s 2100 initially appears to do so more than most. Ranged across two rooms are seven paintings of varying sizes, bijou to engulfing. Each is nearly black – the subtle colour variations establish themselves later – and pricked with whitish dots: night skies, then. Or rather, given that the base of each dark rectangle, framed by a bezellike enclosure of bare brown linen (and then a walnut frame), curves slightly, night skies as if seen on a monitor. Indeed, the Swedish artist has based these works on computer projections of how the stars will arrange themselves on 1 January 2100, with the speculative viewer looking variously south, east and north, in locations ranging from Berlin to Minsk, Venice to Kaliningrad.

You’d have to be a more expert stargazer than me to recognise these patterns: on a good night I can just about identify Orion’s Belt. But the conceptual undertow becomes clear and persuasive enough while one moves from work to work, and simultaneously notes how materialist these paintings are – the tiny star-dots, ringed with the colours of the work’s underpainting, are embedded in thickly impastoed monochrome fields built from febrile brushstrokes that nod back to Van Gogh’s 1889 The Starry Night (also the name of the predictive computer program the artist used) and range in shade from midnight blue to nearly brown. Like looking at the real heavens on a clear evening, the longer you look, the more you see; and while that’s happening, the works accumulate associative depth.

For Fägerskiöld, after nodding neatly to the modern aesthetic past via Postimpressionism and all-over abstraction, is zooming past the present to do something that, seemingly, precious little contemporary art can find the wherewithal for: contemplating the future. As the handout notes, this places the work in the predictive tradition of, say, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), whose narrative, we now know, wasn’t wholly accurate. Fägerskiöld, by contrast, doesn’t postulate what’ll be happening on Earth in 78 years’ time. Instead he offers a prediction at once cold and strangely reassuring. In the worst-case scenario, there won’t be people here to see these diverse firmaments; but the stars themselves will still be hanging there, unconcerned.

Paul Fägerskiöld, 2100

Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin, until 12 March