In the German artist’s first solo institutional show, we’re all just strangers on a train

For decades German trains symbolised the country’s postwar efficiency, but in recent years Deutsche Bahn has declined. Semi-privatised and crumbling, the network is routinely subject to delays, and waiting for a cross-country train can feel like watching irony itself arrive belatedly into the national culture. Yet if your train runs, and isn’t too overcrowded, you can still enjoy the Bordrestaurant: a dining car serving hot meals, coffee in china, beer in glass. This is the setting of Paul Niedermayer’s DB, the German artist’s first solo institutional show: 30 photographs made over two years of train journeys, observing how others carve out moments of leisure between cities.

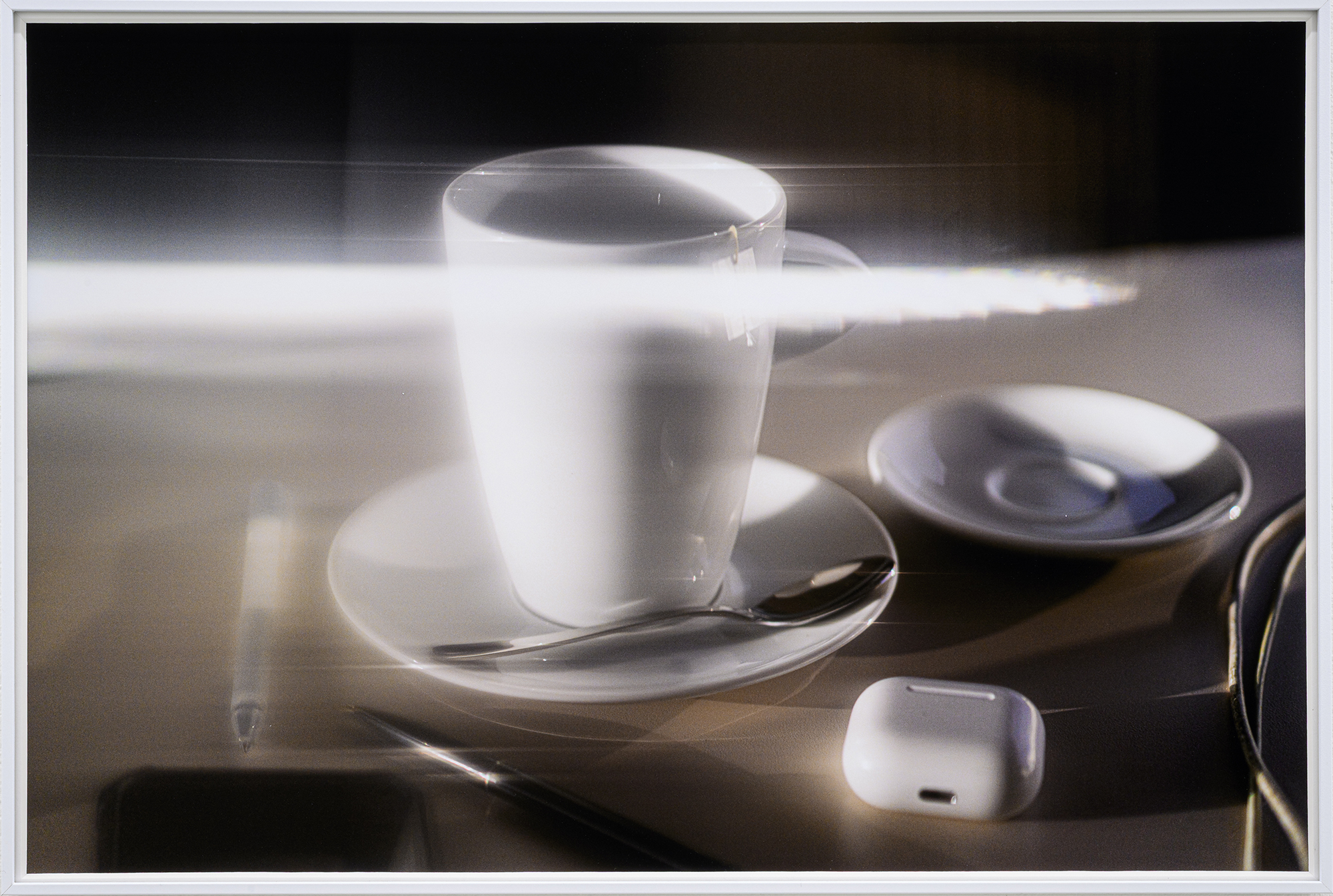

We might call these works still life. Closely framed scenes of Bordrestaurant tabletops, they depict what remains after a diner or drinker has gone: a tall beer glass, drained (No. 3644, all works 2025); coffee cups alone (No. 1189) or in pairs (No. 2167). An iPhone earbud case beside a Muji pen and porcelain mug, instantly recognisable even without logos (No. 0284). A handful of smartphone images of beer glasses, snapped in portrait format, sit alongside landscape-format photographs taken on a mirrorless full-frame camera, for which Niedermayer arranged leftover objects for formal effect. The two modes are displayed together, all colour photographs, each print 36 × 53.5 or 48 × 36 cm and presented in a white frame. They’re sequenced in a band across three walls of the gallery, in groupings that generate an impression of speed and travel, as though the train’s motion were accelerating and slowing within the exhibition.

This feeling of speed intensifies the effect of the lens filter used by Niedermayer to create a sense of blurred motion, as if the pictured cup, say, was whizzing past the viewer, rendering the photographic image as a smeary painterly surface. The result recalls Gerhard Richter’s paintings of his Third Reich-era family photographs, such as Uncle Rudi (1965), smiling in his SS uniform – memory’s ambivalence is enlarged and distorted. Though if Richter used painting to estrange the documentary record, Niedermayer turns contemporary technology against itself, making digital images appear handmade.

Most the works, with four exceptions, are titled only by their file sequence number, underscoring the scenes’ generic repetition and the anonymity of the travellers. We glimpse an occasional hand or arm – someone steadies a glass, a man gestures at an out-of-frame companion – but no commuter is ever granted a full identity. Richter is not the only mid-twentieth-century figure whose legacy lingers in this distinctly German exhibition. Bernd and Hilla Becher, with their impartial taxonomies of industrial architecture, and their Düsseldorf School progeny who became giants of German conceptual photography, also echo here. Niedermayer’s primary concern appears to be the relationship between content and form – a preoccupation out of fashion for some time, yet one that feels surprisingly urgent amid today’s flood of photographic self-expression, as she insists on structure as the condition for meaning-making in photographic images.

A sharp-eyed viewer of the DB photographs may notice that Throwing Ten Dice on My Desk and Throwing Three Dice in the Air, depicting various white dice in motion, were not taken on a train but in a studio. Equally one might not. Small divergences from Niedermayer’s script play as jokes against her project, and perhaps against the worn-out faith in twentieth-century institutions, be they trains, photography or European nation-states. But only lightly, with the half-distracted gaze of a commuter more inclined to watch their coffee cup than check their emails on the ride home: taking pleasure in the leftover spaces of disinterest that late modernity still affords.

DB at Kunstverein Freiburg, through 2 November