Artworks in Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, tell a tale of spiritual bondage both created and witnessed by the camera’s lens

Paul Pfeiffer is not afraid of grandiosity. Neither was Hollywood director Cecil B. DeMille, who, introducing a screening of his 1956 biblical epic, The Ten Commandments (which dramatised Moses leading the enslaved Jews out of Egypt), informed the audience that they were about to view ‘the story of the birth of freedom’. At first glance, the sweeping title may seem out of step with Pfeiffer’s multimedia artwork, which investigates mass culture – particularly spectator sports – and its subsequent mediation in film, television and advertising. But Pfeiffer’s artworks tell a tale of spiritual bondage, one both created and witnessed by the camera’s lens. In video, photography and sculpture, Pfeiffer reveals the eerie religiosity of contemporary media, unveiling the structures that sustain spectacular entertainment today.

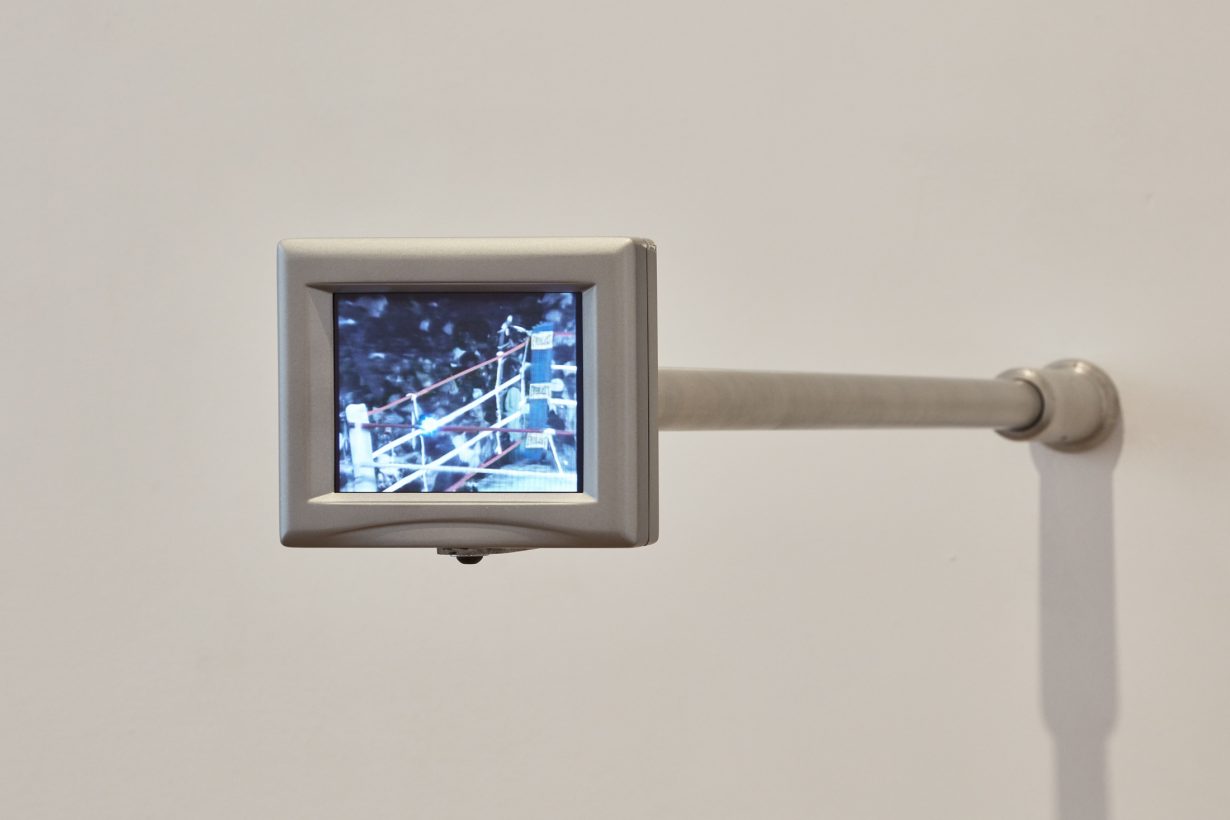

Editing techniques lend Pfeiffer’s found footage a mystical air, resulting in artworks that both replicate and critique the thrall of mass culture. In Caryatid (2003), Pfeiffer alters a video of an NHL Stanley Cup celebration by erasing the athlete holding the silver trophy aloft, so that the award defies gravity as it bobs in front of a crowd. The floating trophy matches the colour of Pfeiffer’s chosen display: a 23cm silver-plated television. The film series The Long Count (2000–01) employs a similar trick, transforming the bodies of Muhammad Ali and three famous opponents – Sonny Liston, George Foreman and Joe Frazier – into transparent plasmalike spectres that swirl within a boxing ring surrounded by a large audience. Pfeiffer presents these films on small screens that protrude on silver rods wall-mounted just above head height, demanding that the viewer strain and bend to discern the action onscreen. Here, television subordinates its spectators and athletes: both must physically change in order to see – or be (partially) seen by – its screens.

Mechanisms of image reproduction are fateful devices, ones that simultaneously exalt and destroy their original subjects. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse photographic series (2001–18) shows solitary basketball players in monumental form, their often-airborne bodies adopting the postures of worshippers ascending to meet the divine. The large colour photographs’ titling refers them to the New Testament’s Book of Revelations, making them both signifiers of oncoming death – the ‘horsemen’ – and faceless victims of its wrath. Media technology creates this apocalyptic scenario: Pfeiffer edits out the numbers and names on players’ jerseys, turning athletes into symbols of biblical proportion; TV monitors, flashbulbs and stadium lights further excise their individuality. In Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (07) (2002), a basketballer raises his hands as though receiving the Last Judgment – but where his face should be is only the blown-out brightness of an arena’s big screen.

Sporting events are also a global export, the product of an invisible system of labour and trade that fuels its power. The Saints (2007) explores this international supply chain: the 17-channel audio installation features the reactions of 1,000 Filipinos hired to watch a recording of England’s defeat of Germany in the 1966 World Cup final. The sound of their emphatic cheers echoes throughout the museum; when I arrived at the installation’s entryway, the noise was so loud I was half-expecting to find a live match – instead, a huge empty room greets the visitor, wall-mounted white speakers projecting the audio across the vacant space. Pfeiffer, who was raised between the Philippines and the US, uses The Saints to reveal the illusions associated with fandom: the homogeneity of team devotees, for example, and their nationalist investments in the World Cup. The emotionality of Pfeiffer’s audience shows both the unseen work behind mass cultural entertainment and how the drama of such events is – or can be – manufactured. Following the awe of the aural installation, Pfeiffer shows its secret source: in an adjacent space, a two-channel video projection displays the original game alongside the paid, roaring crowd, sitting inside a movie theatre in Manila.

What is absent from Pfeiffer’s work is often just as important as what is present. His re-mixed examinations of mass culture have that in common with other theological enquiries: these installations, films and photographs explore communal events that, with television’s help, adopt a near-religious character. In this context, the artist’s overlarge gestures – a title referencing biblical descriptions of Jesus’s birth, for example, for a video of an NBA game edited to remove all players (John 3:16, 2000) – seem appropriate, not ironic. Pfeiffer’s dissections of entertainment illuminate the ways spectacles come to feel magical, a process that obscures or eliminates the people that form their images. When Pfeiffer pulls back the curtain, a camera lies in wait.

Prologue to the Story of the Birth of Freedom at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, through 16 June