A new show at Kurimanzutto, Mexico City marries a sense of heaviness with a patent ethereality

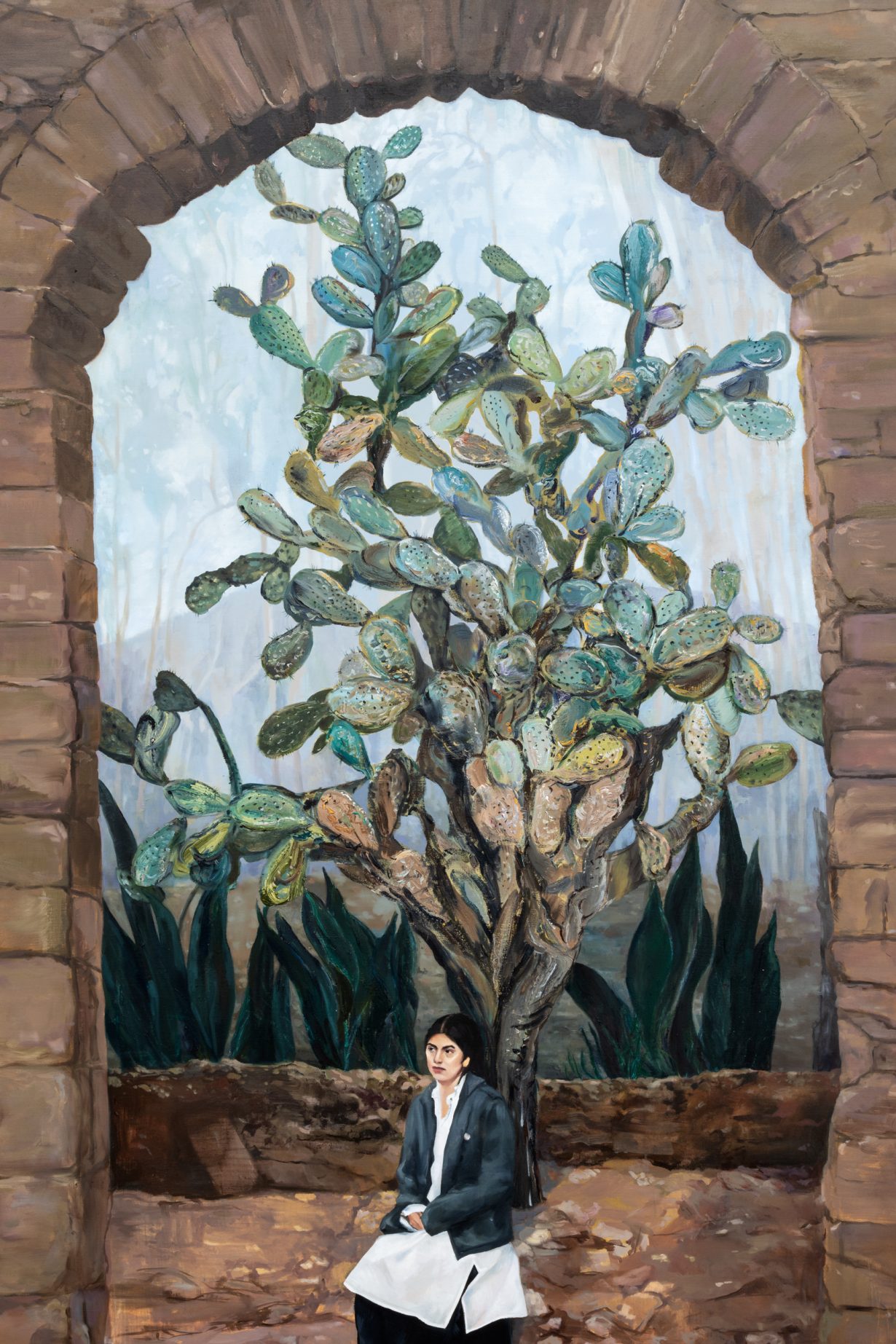

A woman with long dark hair and enviable eyebrows lies listlessly at the centre of Casa No Name (all works 2023), a puzzling, hazy mural. Dark clouds encroach around her, and little is recognisable apart from some architectural ruins that appear in the bottom half of the mural. An actual rock is fixed to the mural, hanging at the woman’s feet: La planta mágica (The Magic Plant) is a piece of carved limestone holding four smaller stones in its crevices. The mural, a highlight of the show, is emblematic of its technical eeriness; nothing is as it appears, the timeline is fuzzy, the visual cues disconnected. The eight murals, for starters, are photographs that were painted by a wall-printing robot directly on Kurimanzutto’s gallery walls, the distinct lines of the printer still visible under the artist’s handmade mists of airbrushed acrylic and her anxious scribbles of charcoal and pastel.

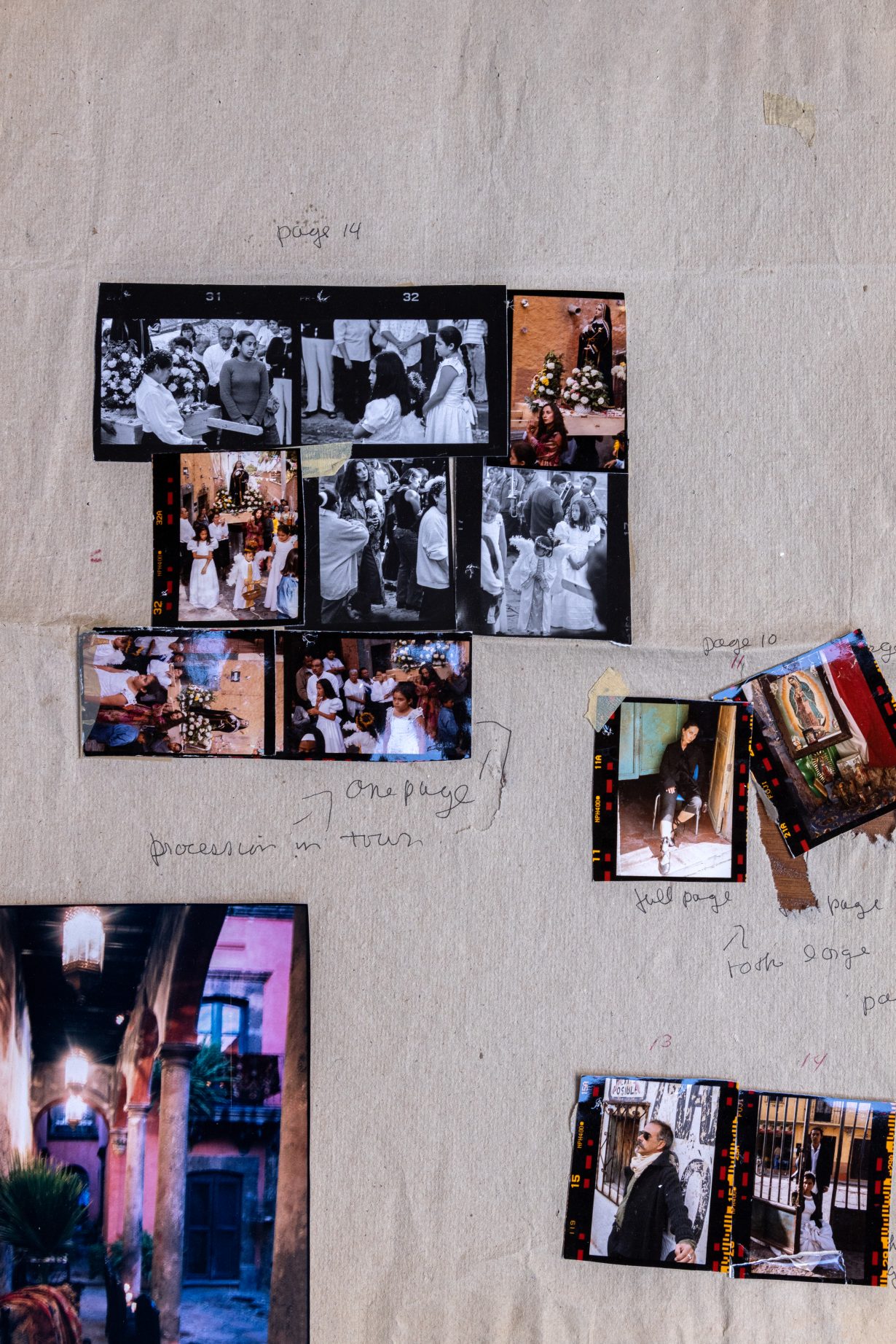

At the centre of it all is the ghostly presence of American photographer Deborah Turbeville, who died in 2013. Widely recognised as one of the three major imagemaking forces in fashion – alongside Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin – she is credited with changing not only the way fashion magazines looked, but with raising the level of their artistic ambitions and expanding the grasp they hold on our collective imagination. Here Olowska takes several visual references from Turbeville: inspired by a series shot in Mexico and Poland during the 1980s and 90s, Olowska collaborated with Polish photographer Jacqueline Sobiszewski to restage the compositions that Turbeville created in Kraków in 1989. Similarly, she recruited Mexican photographer Karla Ximena Cerón and the model and artist Carmen Serratos to re-create some of Turbeville’s compositions in sites around the house she used to own in San Miguel de Allende. Olowska’s versions then became the images in the murals, with the artist’s additions made by hand after the fact.

Olowska excels at invoking Turbeville’s undeniable knack for womanly moroseness, a sense of heaviness that is here personified by the weather. In Potocki Palace a woman clutches her coat close to her chest, her gaze downcast, as she traverses the snowy exterior of a princely abode. In the even more haunting The Augustine by the Chestnut a nun’s dark silhouette is framed by winter-torn trees, completely black silhouettes against the light. Both women sit at the centre of the frame, surrounded by Olowska’s colourful yet unnatural alterations, besieged by an inclement environment that almost seems to come from within them, encroaching upon the reality around them.

Apparently inspired by details found in Turbeville’s images, ten limestone sculptures, made in collaboration with Mexican mason worker Joel Arrieta’s workshop, are enigmatic if not necessarily evocative. Los pasadores (The Bobby Pins) is a rock with a few bobby-pin shapes engraved in it; La oreja (The Ear) is similarly self-explanatory; while the larger ones recreate elements taken from patrician buildings, such as El Palacio (The Palace) and La serpiente (The Serpent). But Olowska really hits a sweet spot with her weaving of narratives: Mexico’s art scene simply can’t get enough of its enduring romance with modernism, its archive-loving exhibitions, its current flirtations with fashion and, more importantly, its own place in Western art history. Olowska winks at all those things here, by integrating Turbeville’s long-lasting interest in twentieth-century aesthetics; her models frequently seem to inhabit the saddened glamour of the interwar period, dwelling in ruined buildings, be they in Mexico or in Poland.

Olowska’s work reminds me that while photography is the preeminent time-composed medium, the images she creates, in their multiplicity, their material time-jumps and their mashup of anachronistic references, achieve an otherworldly timelessness. They embody European postwar melancholy just as they could easily be included in the September issue of Vogue. They appear as in tune with our era of aggressive aggregation – forever in mid-quotation of previous iterations of culture – as they are patently ethereal. They exist, perhaps, in that rarefied realm of work by women creators who always have a foot on the outside, a bit out of step with their revered male contemporaries, no matter how magical, unique and forceful their contributions are.

Resonance at Kurimanzutto, Mexico City, through 20 May