The artist’s latest show at Waddington Custot, London captures the consumer pleasures that the middle classes have enjoyed since the Industrial Revolution

At first glance, nonagenarian British artist Peter Blake’s new exhibition teems with nostalgia – composed of collages and sculptures made of printed materials and ephemera that date from the Victorian era to mid-twentieth century. For a second it feels like Aby Warburg’s Bilderatlas Mnemosyne but for mass culture, created with a taxonomic, almost fetishistic fervour for printed images and kitschy trinkets. In The Big Little Books series (2023), for example, similar images culled from the titular children’s books are grouped together on each A4 page, where cocky superheroes flex muscles at bodybuilders and Roman gladiators (Big Little Books. ‘Galloping Toward Camp’) and variously sized elephants labour under strapped-on palanquins (Big Little Books. ‘Outraged Elephant’). Having presented other solos at Waddington Custot in recent years that focused on his portraits and drawings, Blake’s latest exhibition at the gallery gathers new collages in his signature style, as well as sculptures, for which he is less well known.

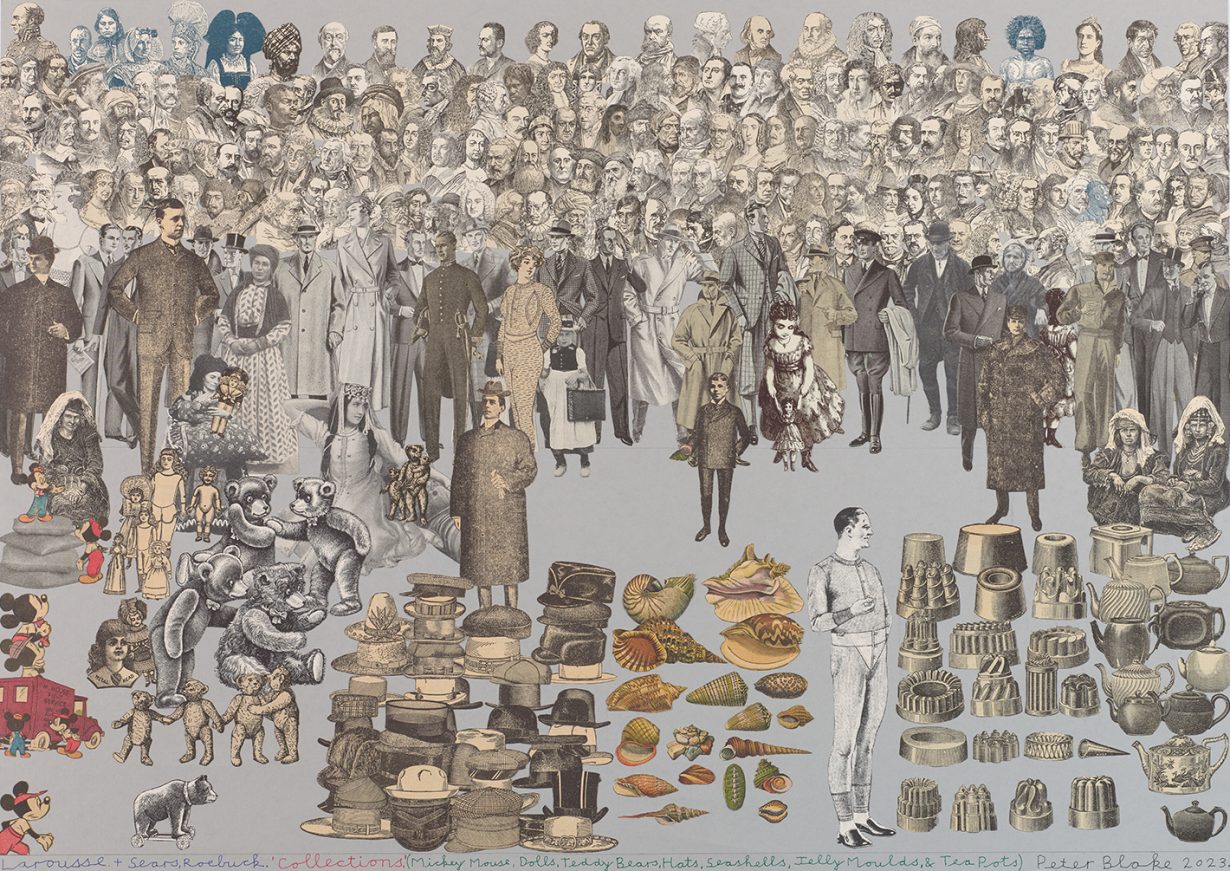

Filled to the brim with figures cut from old comic books, illustrated encyclopaedias and consumer catalogues, Blake’s collage indulges in a surplus of printed or materialist matters – the consumer pleasures that the middle classes have enjoyed since the Industrial Revolution. In Larousse. & Sears, Roebuck. ‘Collections’. (Mickey Mouse, Dolls, Teddy Bears, Hats, Seashells, Jelly Moulds, & Tea Pots) (2023), row upon row of portraits of mostly white male dignitaries, mixed with the occasional ethnographic images of nonwhite subjects – all cut from the late-nineteenth-century encyclopaedia Larousse – look over a rank of fashion catalogue figures drawn from the 1920s or 30s, who themselves look on at the titular array of knickknacks and appliances collaged in the foreground. Rather than saying more about what’s being illustrated – be it clothing style or ethnic groups – these cutouts speak of how sales catalogues and encyclopaedias contributed to what constitutes visual knowledge through a syntax of representation highlighting the visual codes of authority (stern gazes, three-quarter views, sketched in fine lines) and domestic delights (20 kinds of jelly moulds), as well as a hierarchical visual order. One might read it as a suggestion of how agents of empire both literally and figuratively lurk behind a thriving consumer culture. With Blake a self-proclaimed royalist, it is not clear how much of these juxtapositions are offered with a pinch of salt.

If Blake’s collages work with a visual culture structured by the enterprise of the printing press, his sculptural work comprises much more personal hoards, and a more whimsical taxonomic paradigm. In Fort. Siege (2012) – veering between what seems to be the results of a children’s play and some theatrical military operations – groups of porcelain dolls, Native American figurines and toy soldiers are deployed in and around a mediaeval fort, making it look like a sort of dollhouse display in which domesticity and aggression are not so far apart. Others navigate the blurry line between hoarding and collecting fine art. Still Life 4. ‘Homage to Morandi’ (2003) finds modernist shapes among the likes of miniature glass bottles, grouped together to recreate one of the titular painter’s delicate still lifes. Museum of Black & White 12 (in homage to Mark Dion) (2008–10), meanwhile, looks like an exposed curiosity cabinet, with a disparate selection of items ranging from crucifixes to cutlery affixed to a canvas in a tidy grid that highlights their shared black-and-white palette. Referencing conceptual artist Mark Dion – whose own work pokes at the arbitrary way knowledge is catalogued and produced by museums and institutions – the orderly, nonsensical alignment points out how much taxonomy might have to do with aesthetics. In the last room, a series of black-patinated bronze casts of Blake’s assembled found objects are installed upon pedestals – flanking a miniature bronze version of Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column (1938). Alongside the modern artist’s canonical obelisk, these metal replicas of what used to be ephemera take on an air of timelessness.

In Blake’s works, there’s a pleasure in the textures of printed or material matters, beneath which is our desire to see, own and fetishise them, which frames the way we interact with the world. But something more unsettling lingers behind these humorous, flippant gestures. As these hordes of antiquated, discarded items come back to life – or, alternately, as these animated things are reified as waste – they become a reminder of how much stuff we hold onto, and how we now have to deal with our own material legacies.

Sculpture and Other Matters at Waddington Custot, London, 20 February – 13 April