To earn the title Il Magnifico, Lorenzo de’ Medici had to be more than just rich and powerful – he had to be seen as virtuous. He surrounded himself with poets, philosophers, architects and painters, commissioning Botticelli and Michelangelo, but also influencing other wealthy families to be patrons of the arts so as to curry favour with him. History labels Lorenzo as a patron of the arts, who used his wealth to fuel the Renaissance, but it would be an error to think his actions altruistic. For one, Lorenzo understood that artisans were an economic backbone of Florence, and that attracting wealthy merchants and financiers from across Europe enhanced the city-state’s soft power. But he also understood patronage as a means of preserving his family’s grip on power. In the chapter ‘What a ruler should do to win respect’ of his 1532 treatise The Prince, Niccolò Machiavelli made the logic explicit: ‘A ruler must also show that he admires achievement in others, giving work to men of ability and rewarding people who excel in this or that craft.’ Respect, for Machiavelli and de’ Medici, was to be engineered – and art was one of the instruments by which to do it.

Throughout the history of philanthropy in the arts, whether we are looking at Renaissance Florence, Victorian England or postwar New York, the motivations the wealthy have had in supporting the arts can generally be grouped into three main categories: status, altruism and access. But despite this inevitably tangled mix of motivations, from the noble to the more self-serving, understanding the dominance of one over the others is key to understanding how we have built the art institutions we have today, and where philanthropy in the arts might take us in the future.

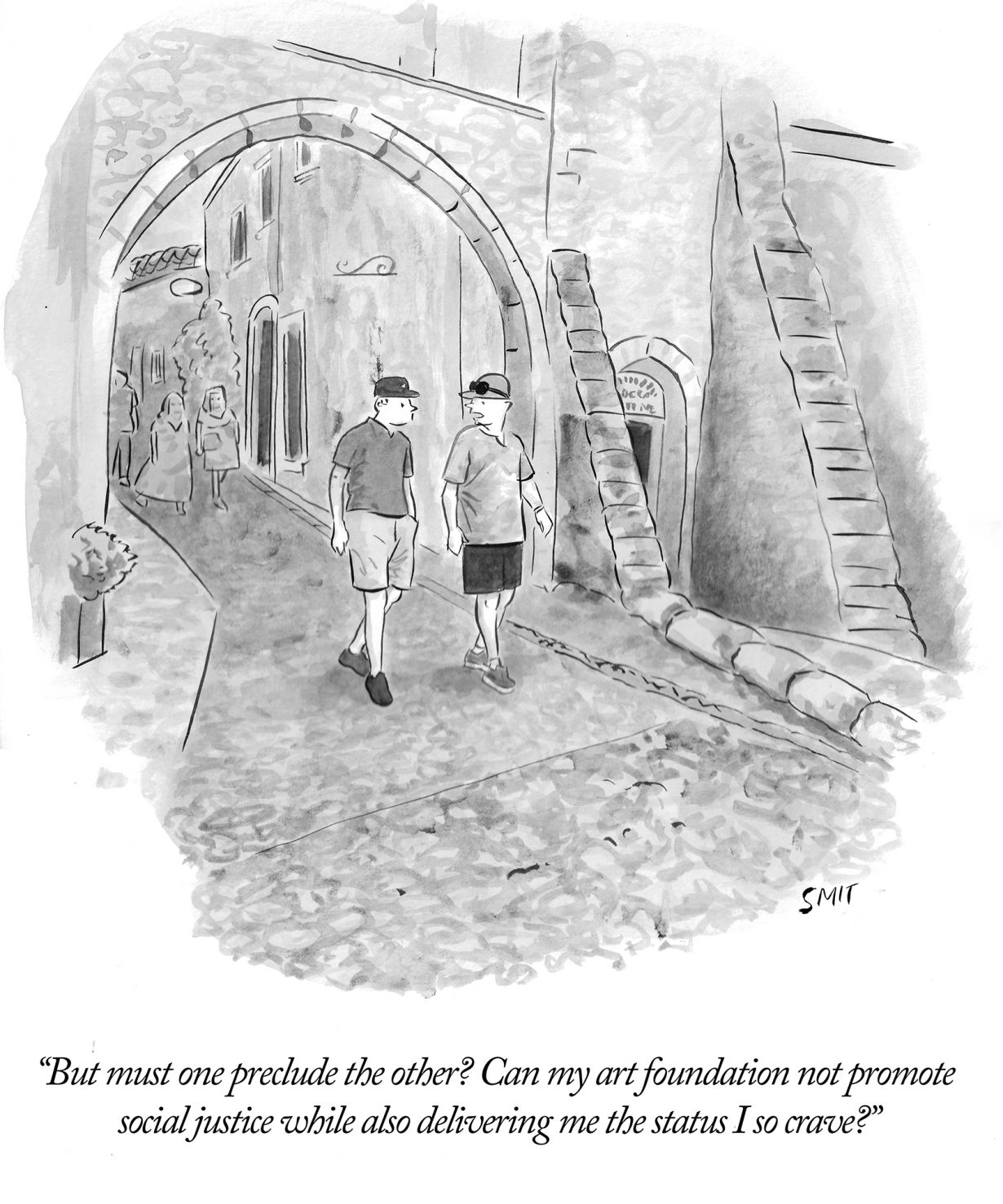

Of these motivations, status is the wish to accrue cultural capital, or to associate oneself with refinement for others to see. It can be the desire to be remembered as a patron, to have a legacy or even just to show off in front of your peers. Altruism, by contrast, is driven by a belief in the value of the arts, whether to lift communities, democratise culture or simply support artists, for little or no personal benefit. Indeed, for some the difference between a philanthropist and a patron in the arts is some vision and generosity that goes far beyond what is given in return. Lastly, or perhaps somewhere in the middle, there is access, wherein the appeal of supporting the arts lies in the experiences and relationships it affords – access to curators, to private viewings, to artists themselves and to networks of like-minded collectors and enthusiasts.

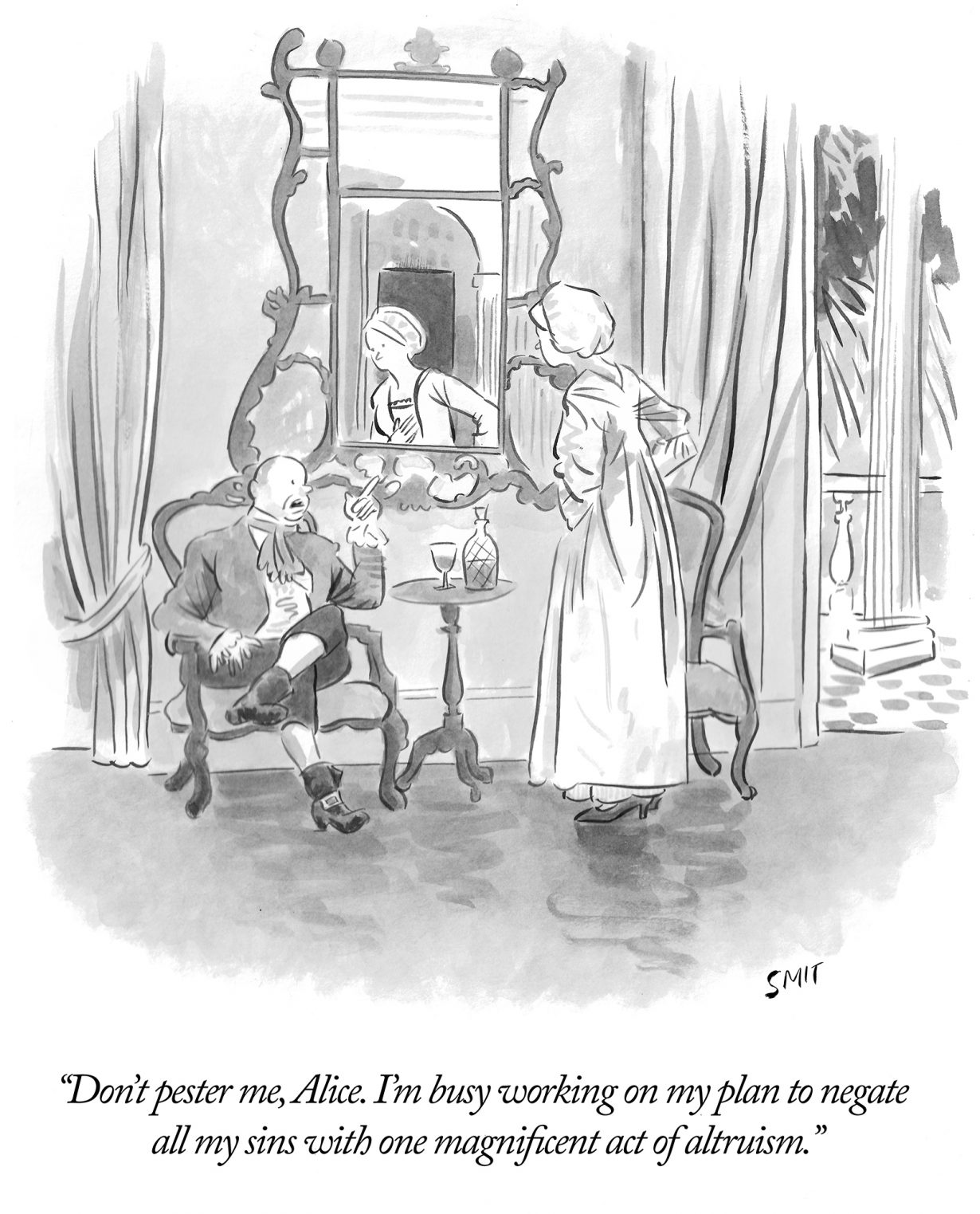

These motivations are not mutually exclusive. A single donation may simultaneously serve a donor’s moral convictions, elevate their social standing and deepen their personal engagement with the cultural world, but what is key in any evaluation of philanthropy in the arts, past, present and future, is the balance. To be a ‘Medici’ in any honest sense is to be motivated by the pursuit of status far more than by altruism or access. Indeed, this could be said for most royal and ecclesiastical patronage throughout history. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that altruism was put more to the fore, marking a crucial shift in how the wealthy understood their responsibility to society, and laying the foundations of our modern culture of philanthropy.

For most of history, to be a philanthropist, as opposed to a patron, was to be focused on alleviating poverty. But during the nineteenth century, philanthropy began pivoting away from almsgiving towards improving the general education and wellbeing of the public. In part, this was because new censuses in the uk and us began showing the true extents of poverty, with the responsibility for structural inequality laid at the state’s feet, rather than private wealth’s, but it was also due to new Victorian thinking that exposure to great literature, art, philosophy and music could elevate the individual and improve society.

Matthew Arnold, the Victorian poet, cultural critic and school inspector, believed that culture was not merely entertainment – it was moral and intellectual refinement, and a necessary antidote to industrialisation, social disorder, populism and anti-intellectualism. It was Arnold who adopted the word ‘philistine’ to describe the narrow-mindedness, materialism and cultural indifference of the newly wealthy middle classes. By the latter half of the nineteenth century, some of the world’s richest people, in Europe and particularly in the US, would fully embrace Arnoldian views, most famously Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish-American steel industrialist, and one of the wealthiest within America’s Gilded Age. Art, as Carnegie wrote in his 1889 essay ‘The Gospel of Wealth’, should be supported ‘to give pleasure and improve the public taste’ and through ‘public institutions of various kinds which will improve the general condition of the people’. Thus, his name appears on libraries, concert halls, educational initiatives and cultural institutions – institutions, in his words, that would ‘help those who will help themselves’.

This moral imperative, this altruistic bent, formed a foundation of arts philanthropy, and can be seen over and over in the founding and support of arts institutions by individuals across Europe and North America well into the twentieth century. In 1861 the German financier Joachim Heinrich Wilhelm Wagener, a believer in civic arts education, left his collection to the Prussian Crown, and it became the basis for Berlin’s Alte Nationalgalerie. Several decades on, sugar magnate Henry Tate funded the building of, and provided the founding collection for, the new Tate Gallery. At its inauguration, in 1897, the politician William Harcourt praised Tate, saying that ‘The wealth of [the United Kingdom] is increasing in a marvellous degree… and we have to learn the best use that can be made of that wealth, and I think Mr Tate has given a noble lesson and an admirable example.’ In 1929 Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, along with Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Quinn Sullivan, cofounded the Museum of Modern Art. Their support for modernism was radical at the time, but their conviction that contemporary art could nourish the public soul just as effectively as European masterworks followed the dogma. Andrew Mellon, another US industrialist, began rapidly acquiring masterpieces during the 1910s (including a group of works in 1931 from the Hermitage Museum via Stalin) with the explicit intent of creating a free national museum for the American people – the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC – to rival the great museums of Europe. Like Tate, he funded its construction and donated his personal collection, but he also established a sizeable endowment.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the consensus that the arts are a civic necessity worthy of support for the benefit of the people has only solidified. But while many countries established structures for state support, for example the Arts Council in the UK, lessening their reliance on benevolent philanthropists, the US continued to make philanthropy a hallmark of American elite identity, with altruism as the primary, or at least secondary, motivation for arts philanthropy.

For the past quarter century, the world’s wealthiest have become richer and more numerous, and philanthropy has become more internationalised. There are still those who follow the model set out by Carnegie and Rockefeller. Michael Bloomberg, for example, has dedicated around $21 billion to philanthropy over his lifetime across 150 countries, with a large portion of this going to the arts. In March 2025, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago announced a $10 million anonymous gift to create a dedicated endowment for performance, ensuring long-term support for a medium that is notoriously difficult to fund and has struggled to attract philanthropic attention. This gift, which will back commissions, collecting and archiving, exemplifies a type of giving that is done not only with a belief in the intrinsic value of the arts, but which also identifies a structural gap and seeks to fill it.

This last can also be said about the rise of private museums, institutions built by individual collectors to house their collections, which in contrast to what Tate and Mellon did are completely controlled by the founders. Many private museums are, of course, founded for reasons of status and access (often to art-market opportunities), or due to a frustration, distrust or lack of interest in existing public institutions. But when motivated by altruism, private museums have been an excellent philanthropic tool to fill structural gaps. For instance, the Samdani Art Foundation in Dhaka, which aims to provide an infrastructure of support and opportunities to the country’s contemporary artists where there was previously very little. Or the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, which was founded in 1995 to support new generations of contemporary artists.

To trace the history of arts philanthropy is to observe how the core motivations have been rebalanced over time, reflecting the values and ambitions of each era. Historically, much of arts philanthropy has been rooted in a belief – sometimes moral, sometimes paternalistic – that certain kinds of culture are good for people. Current trends in arts philanthropy are connected to what the wealthy believe is ‘good for people’ today, which continues to evolve from the past, and from what built the institutions we know today. As a result, museums are having to evolve in response, to prioritise digital accessibility over physical spaces, or experiential, participatory work over static collections, or to eschew art for art’s sake, only viewing the arts as relevant when they intersect directly with social justice, mental health or community engagement. For example, the $1m donation from philanthropist Eileen Harris Norton to the Baltimore Museum of Art in 2021 for short- and long-term diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion initiatives, or the Art for Justice Fund, founded in 2017, which supports ‘the work of artists and advocates seeking to end mass incarceration’ in the US.

And then there’s the impact of technology on two fronts. The first are the new tech elites in the US, who have the wealth to carry the baton for arts philanthropy but currently have little interest in the arts. This has largely been put down to their nature as engineers and mathematicians, the thinking being that they find it much easier to grasp, and relate to, what can be quantitatively measured. This is why the uptake for effective altruism, the latest trend in philanthropy, which uses evidence and reason to maximise positive impact, has been so strong in the tech community. And given this group’s stated commitment to disruption, it would be misguided to hope that support for the arts would carry on at current levels if only or even primarily in the hands of Silicon Valley.

And so members of the ‘smartphone generation’, still mostly under twenty-five, are absorbing the tools and narratives that shape how they see what is valuable to society, making it too early to know what impact they will have. If they come to perceive art as a luxury, an asset or mostly just a status symbol, their philanthropy, or lack thereof, will reflect that. For there to be art philanthropists in the future who are motivated by altruism more than the pursuit of status and access, they must be guided, supported and encouraged to believe that art is a public good, a space for empathy, critical thinking and shared experience – beyond the market, beyond the metrics and beyond the algorithm.

Leslie Ramos is a adviser based in London

Guy Richards Smit is a performance artist and cartoonist based in New York

ArtReview’s May 2025 issue is accompanied by a standalone publication on philanthropy in the arts, with essays exploring funding models in North and South America, Africa, Europe and Asia, profiles of four prominent philanthropists and a guide to philanthropic initiatives around the world. This publication was created with the support of Durjoy Bangladesh Foundation, Han Nefkens Foundation, Levett Collection and Sunpride Foundation.