The Dancer, Evelyn Juers’s biography of Cullen, charts not only the Australian experimental artist’s life, but also her ancestry, the settler-colonial history of Australia and the larger sociopolitical context of her time

The Australian dancer Philippa Cullen died in 1975, in the Indian town of Kodaikanal. She was just twenty-five. By then, though, Cullen – also a choreographer, performer, musician and teacher – had become a key figure in the Australian experimental art scene. At the forefront of the electronic music movement, she worked with composers, engineers, mathematicians, academics and artists to construct movement-sensitive floors and theremins. In addition to India, she had travelled to Germany, the Netherlands, England, Ghana and Nepal. She had danced in opera houses, trains, country towns, galleries and parks. And she had taught dance to conventional students, inmates at Long Bay prison in New South Wales, psychiatric patients and at children’s summer camps. In her essay ‘Towards a Philosophy of Dance’ (1973), quoted here, Cullen wrote: ‘I would define dance as an outer manifestation of inner energy in an articulation more lucid than language’.

A key aspect of Cullen’s vision was her approach to the relationship between movement, technology and composition. Influenced by Merce Cunningham and John Cage, she investigated methods for using biosensors and computer algorithms in performances, and experimented with directional photo-electric cells to transform improvised dance into sound. For Australian audiences at the time, these performances proposed inventive new ways of thinking about dance.

As the title suggests, the book is for Phillipa Cullen, and as such, it is far from a conventional biographical narrative. Its own choreographic feat, it charts not only Cullen’s life, but also her ancestry, the settler-colonial history of Australia and the larger sociopolitical context of Cullen’s time, interspersed with literary references, quotes and dream sequences. Set among this is Cullen herself, who kept diaries, recorded her research, notated dreams, made diagrams for dances and sent letters. Juers has chosen to italicise direct references within the text, so the reader must continually switch between the present- tense ‘I’ of Cullen and the ‘she’ of Juers: ‘She needs to be patient and devote herself utterly to her work. Sacrifice myself to it.’ This gives a sense that Juers is writing alongside Cullen, instead of speaking for her, and Cullen’s voice – strident, funny, restless, elated, critical – announces itself on the page: ‘I haven’t met anybody who accepts what I do without question’. The result is a sensitive and profoundly moving account of the young artist’s life – her discoveries and joys, her devotion to her work and her vision of dance as an ‘integrative art’.

Throughout The Dancer, Juers pays careful attention to the web of academics, artists, writers and performers that Cullen, directly

or tangentially, interacted with. These include the Austrian dancer, teacher and choreographer Gertrud Bodenwieser (whose dance school Cullen attended as a child), the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (with whom Cullen had a lengthy affair) and Mirra Alfassa, founder of the Sri Aurobindo Ashram and the ‘universal township’ of Auroville, which Cullen first travelled to in 1973. For Juers, the complex lives of these individuals – their histories and trajectories – feed into larger concerns, whether the aftershocks of the Second World War or the aspirations of 1970s countercultures. Juers’s eye is not uncritical though, and she repeatedly draws attention to the ways in which art movements, such as modern dance or the postwar avant-garde, are entangled in their broader historical context.

Cullen’s work was featured as part of the group exhibition Know My Name at the National Gallery of Australia in 2020. In the accompanying publication, the artist Diana Baker Smith lamented that ‘Cullen’s legacy has become as ephemeral as folklore, reliant on oral histories and a handful of old photo- graphs and video tapes’. The Dancer offers a rejoinder to this absence. It is a vast tapestry, woven together by the energy of Cullen’s own voice – alive, and in the present tense.

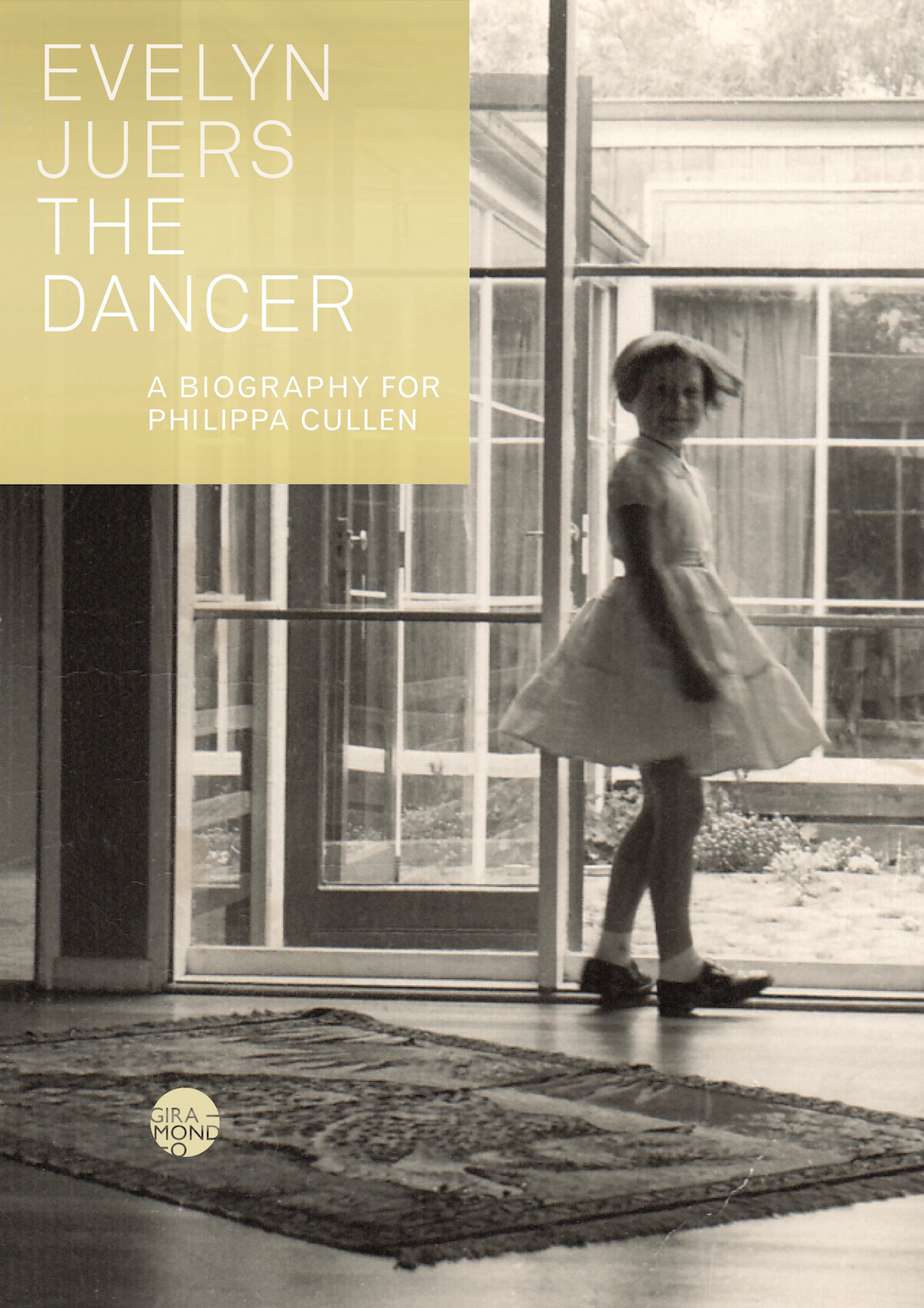

The Dancer: A Biography for Philippa Cullen by Evelyn Juers, Giramondo Publishing, AUS$39.95 (softcover)