Philosopher of her own Ruin at Bonner Kunstverein explores artists’ particular ways of enduring despite apparently coercive circumstances

The contemporary artworld runs on expansionist energies and growth: rare is the artistic project that’s pinned to self-limitation. That’s the case, though, with Philosopher of her own Ruin, a group show for which the dimensions of the Bonner Kunstverein were reduced on curator Alan Longino’s say-so, his capacities limited by the cancer that would end his life. (Born in 1987, the American art historian died last July.) Longino’s surrender to this reality inflects the show’s premises. Bodily erasure and/or transformation are its central themes: the nine positions showcased by a cross-generational, international grouping of artists reflect their individual attempts to transcend political, social or biological constraints, and embody various forms of empowerment through transmutation.

The show’s title is borrowed from Canadian poet and essayist Lisa Robertson, who coined the phrase in an essay in which she discusses menopausal women as ‘dandies’, noting that their organs’ incapacity for ‘family or spectacle or state’ removes them from any (re)productive economy. Longino’s exhibition draws parallels between menopausal and sick bodies – finding that their detachment from societal utility allows them a kind of freedom. The exhibition’s pale grey walls and soft lighting create an intimate atmosphere, individual spotlights illuminating each work, allowing them to breathe yet converse. Sydney Schrader (b. 1987), Bertram Schmiterlöw (1920–2002) and Rosemarie Castoro (1939–2015) come from different eras but all depict bodies that transcend established identities: Castoro’s minimal steel silhouette of a profile, Sarcophagus Self-Portrait (1994), contrasts with Schrader’s Untitled series (2025), in which an ill-defined body shifts position from work to work, and Schmiterlöw’s painting Sömnen (The Sleep, c. 2000), in which an ageing white male floats in space in a trance. Both of these suggest a transcendent circumventing of biological constraints such as ageing or illness. This freedom can also be found when bodies are otherwise pressured: in Anna Bella Geiger’s black-and-white film Passagens 1 (1974), the Brazilian artist’s constraints were primarily political. Her film, shot in Rio de Janeiro under dictatorial rule, shows her walking upstairs, seemingly performing a minimal form of self-expression in what was otherwise a censorious environment.

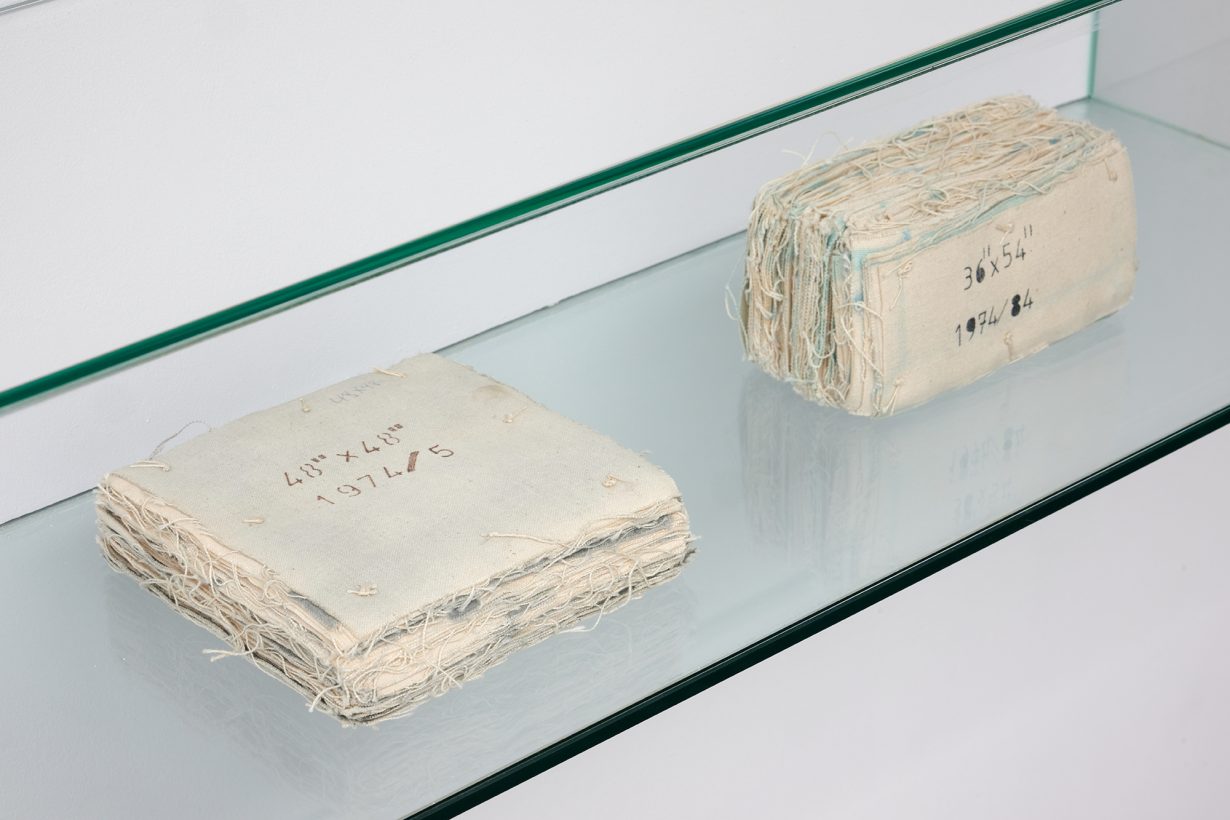

Miyako Ishiuchi’s C-type print Mother’s #54 (2002) features a photograph of a lipstick that belonged to her late mother. Following her mother’s death, Ishiuchi documented many of her remaining possessions during the 2000s, enhancing their presence almost monumentally through dramatic closeups. The shifts in scale turn the relics into abstracted testimonies to time’s passage and the inexorable changes of life. Susan Hiller’s Painting Block (10): 1974/84, 36″×54″ and Painting Block (1): 1974/5, 48″× 48″ (both 1980) appear in a vitrine as stitched-together blocky segments of previously exhibited canvases, printed with the size and dating of the originating works. The format’s dissolution is recast as powerfully transformative, the new entity appearing self-sufficient even though the original imagery has been erased.

In her essay Robertson frames the nineteenth-century French poet and critic Charles Baudelaire’s transformation of his own obsolescence into something durable as a dandyish achievement. Philosopher of her own Ruin ultimately appropriates this premise and embodies this spirit, deploying artists’ particular ways of enduring despite apparently coercive circumstances. Longino’s digressions around invisibility and self-defined autonomy were part of both his wider research – into the dematerialised practice of Japanese conceptual artist Yutaka Matsuzawa, for instance, whose Quantum Art Manifesto (1988) he republished – and his own tragic reality. Philosopher of her own Ruin acts as a final, valuable autobiographical expression, and is a keystone in Longino’s legacy.

Philosopher of her own Ruin at Bonner Kunstverein, Bonn, through 27 July

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.