At State of Concept, Athens, a survey of Attia’s decade at the forefront of decolonial art practice

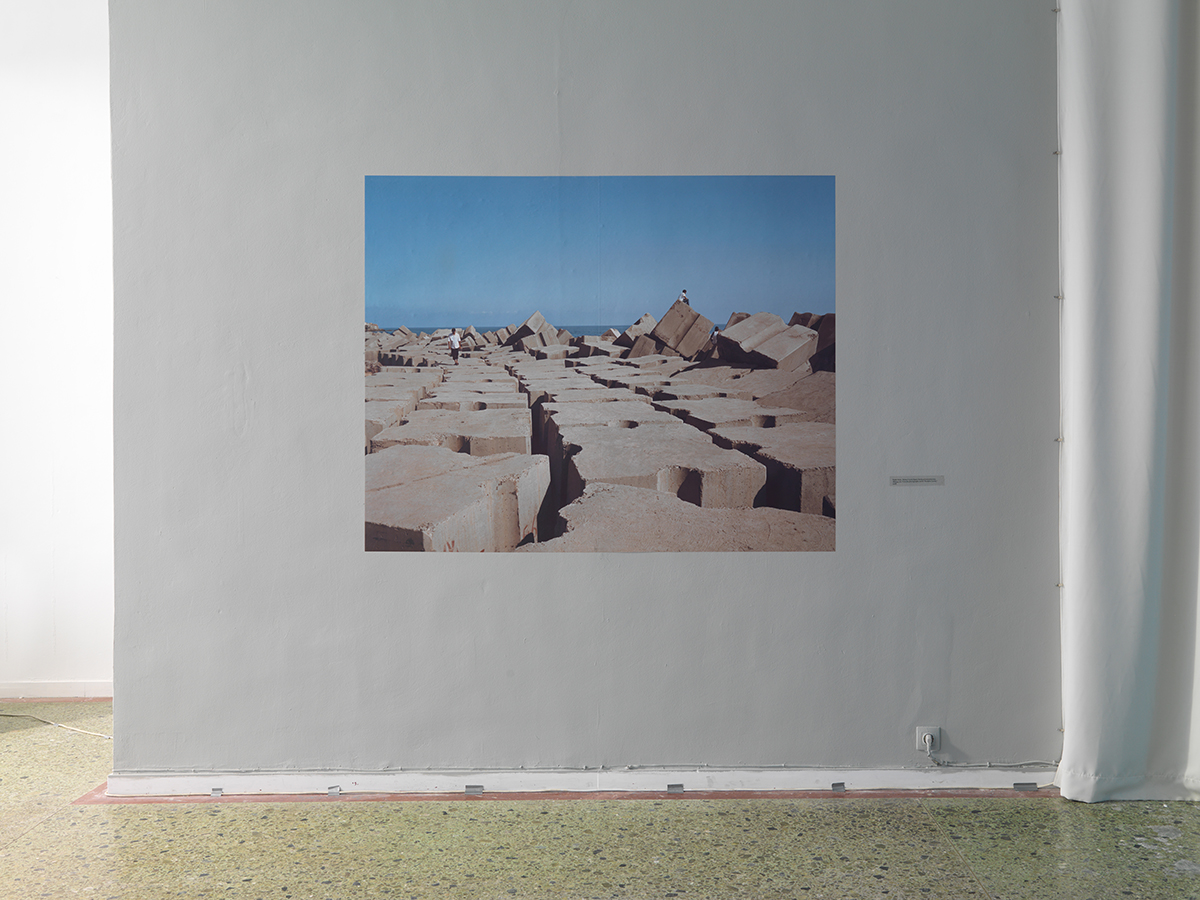

The visitor to Kader Attia’s exhibition at State of Concept enters a small enclosure created out of temporary security fencing staked in concrete blocks. Alongside two flat-screen monitors, a smattering of A4 printed texts are attached to the wire mesh cage by cable ties: closer inspection reveals them to be articles from Western news outlets on the ‘migrant crisis’.

Once I have read a few of these stories, the only thing left to do is sit on the plastic chair and watch the subtitled interviews playing onscreen. That this minimalist installation is one of the few concessions to the affective strategies that conventionally distinguish art from documentary gives you an idea of the show’s character; that I sat there for close to two-and-a-half hours on my first sitting speaks to how compelling the material is; that this accounted for less than half of the five-hour duration of this work alone hints at the demands it makes of the viewer.

Reason’s Oxymorons (2015) is a compilation of 18 short films on the subject of Western and non-Western approaches to psychiatric health. Through interviews with mostly Francophone ethnographers, ethnopsychologists and ethnomusicologists – with interludes from musicians and philosophers – the selection introduces the dominant themes and forms of the exhibition: the continuing failure of the West to acknowledge the limits of its own empire and epistemology, explored through talking-head conversations with academics and non-academics on subjects from the West African animist tradition of Ndeup to the restitution of looted artefacts. Because it takes a while to pick up the thread, my attention is drawn to the homes and offices in which the speakers are filmed. And what’s startling here is how many of these academics talking about the relation of psychological disorder to forced displacement speak from the comfort of offices decorated by African masks, sculptures and ritual objects.

That this is slightly shocking – like spotting a stuffed head behind someone delivering an online lecture on species conservation – might be the highest compliment to the work in this minisurvey of Attia’s decade at the forefront of decolonial art practice. Projected onto a standing screen at the back of the gallery, The Object’s Interlacing (2020) directly addresses the restitution of displaced artefacts from Western museums and exposes how the principles upon which those institutions are founded continue to serve the purposes of colonial power. That it is not perfectly coherent is to the work’s credit: the jarring juxtaposition of a Parisian psychoanalyst with a West African blues musician is one means by which Attia unsettles conventional patterns of reasoning in order to challenge the academic tendency to categorise, compartmentalise, ring-fence and control. The Body’s Legacies: Part 2: The Post-Colonial Body (2018), in which four decolonial thinkers explore the institutionalised nature of police brutality against France’s Black population, makes explicit how abstract systems are enforced through the perpetration of violence against individual and collective bodies. Attia’s reluctance to privilege one form of thinking over another is a way of resisting the kind of cold calculation that continues to be used to justify real harm.

Attia’s project is necessarily generalising, and the breadth of his brush can sometimes paint over the nuances of cultural exchange or oversimplify the analogy between physical and psychological exile. Yet one means by which these films are distinguished from the academic institutions they critique is by generating a productive dialectic with the local context in which they are shown, rather than affecting to stand above it. In the shadow of the Parthenon, issues around restitution, repair and the instrumentalisation of culture to serve a European mythos take on a specific hue; when the daily news is of an authoritarian government’s encampment of refugees in makeshift prisons, temporary security fencing carries a resonance.

Perhaps because I experienced it as a coda to the longer moving-image works, the most affecting film in the show lasts only two minutes and features no words. La Tour Robespierre (2018) is a single shot of the modernist facade of one of the ‘grands ensembles’ that house the immigrant populations of Paris, shot by a drone ascending steadily from bottom to top. At a squint, the camera might be tracking over the canvas of a De Stijl painting. The work reveals how closely the principles underpinning high modernist art and architecture – the supposed apotheosis of reason and creative autonomy from the world – are related to those of state surveillance and control. At the conclusion of the drone’s ascent, it peers over the building into an open landscape. Then, on a loop, it returns to the bottom and starts again.

Kader Attia: The Museum of Repair at State of Concept, Athens, 14 April – 19 June